THE ENTHRALLING CULTURAL HERITAGE OF RAMAYANA ACROSS SOUTHEAST ASIA

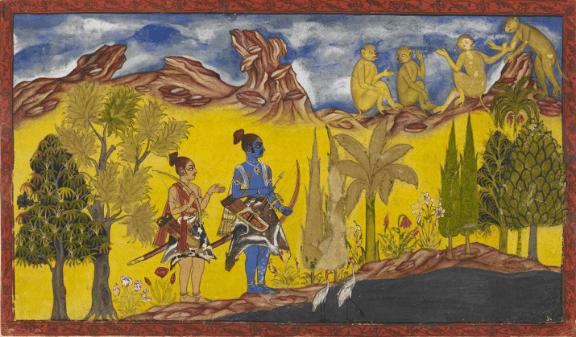

Venerated as the most finest colossal epic of the Hindu Literature, the Ramcharitmanas or Ramayana is still widely read and referred to in not only India but also has been deciphered into numerous versions inked and archived across regions of Southeast Asia, Africa, Caribbean and Oceania. Entailing around 24,000 verses, the Ramayana also known as ‘Adhikavyam’ meaning the first poetic composition lauding the laurels of Lord Ram who is believed to be an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, was composed in Sanskrit by Sage Valimiki in the fifth century BCE. Lord Ram is believed to have taken birth in the ‘Treta Yug’. i.e., about 1.29 million years ago. It’s a grandiloquent saga which narrates the adventures of Rama, his brother Lakshmana, and Rama’s wife Sita, who was abducted by the demon king Ravana.

For millennia, the Ramayana has been a highly revered spiritual literature in India which is widely read and recited. The earliest version, called the ‘Valmiki Ramayana,’ has been translated into many other languages and has over 300 versions like Ramcharitmanas by Goswami Tulsidas for thousands of years. It has been adapted into folklore, puppet shows, and countless oral retellings in both towns and villages.

Ramayana beyond the Bay of Bengal

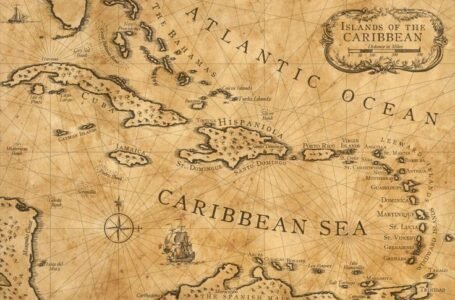

Beyond the Bay of Bengal, the Ramayana has played a significant role in spreading Indian culture globally. Its widespread reach demonstrates the extent of Indian travel and cultural influence over the centuries. The Hindu epic has profoundly shaped Indian philosophy, spirituality, and culture for thousands of years and has also influenced various regions in Southeast Asia and other parts of the world. During the early Christian Era, the Ramayana’s profound reach was not only confined to countries like Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, China, and Tibet but by the 19th century, it had also become popular in parts of Africa, the Caribbean, and Oceania. The recent release of a first ever stamp depicting Ayodhya’s Ram Lala by Laos is a testament to the shared cultural legacy since time immemorial between both the nations.

Buddhism served as a bridge through which Ramayan travelled into the region of Southeast Asia and the character of Ram became prominent in both Jain and Buddhist texts. The Dasarata Jataka’s widespread popularity led to its adoption by kings to legitimise their rule, exemplified by an 11th-century Burmese inscription that declared King Kyanzittha as an incarnation of one of Rama’s relatives.

In Southeast Asia, the spread of Hinduism, Mahayana Buddhism, and later Theravada Buddhism was aided by Odia and Tamil sea merchants and traders in the fourth century BCE who exchanged goods and stories during their annual voyages. Hanuman, a key character in the Ramayana, is portrayed differently in some Southeast Asian versions, often as a clever trickster who outsmarts others. Despite these variations, Rama remains the central figure in most adaptations of the Ramayana in Southeast Asia.

The trade conducted with Khmer Kingdoms like Funan and Angkor, as well as Srivijaya, established strong economic and cultural connections for Hinduism to penetrate in Southeast Asia. Many traders and scholars remained in the region, either by marrying local women or finding employment there.

Glory of Ram in Thailand

Ramakien meaning ‘glory of Ram’, the Thai version of Ramayan which is known to the Thais since the 13th century, is one of the greatest works of Thai literature, deeply ingrained in their culture since it was first introduced to the people of Thailand and is still taught and read in schools. Derived from the old Khmer sources, which explains its resemblance to the Khmer title Reamker, various new versions of the story have been written often by royal authors since the 16th and 17th centuries.

The Ayutthaya kingdom (1350–1767) in Thailand is believed to have been modelled after Ayodhya from the Ramayana. According to a UNESCO article about the city of Ayutthaya, when the capital of the restored kingdom was relocated downstream and a new city was established at Bangkok, there was a deliberate effort to replicate the urban layout and architectural style of Ayutthaya to mirror the perfection of the mythical city. Although many Thai manuscripts were lost during the destruction of Ayutthaya in 1767, the Ramakien currently recognized was compiled in the Kingdom of Siam, now Thailand, under the direction of King Rama I (1782-1809), the founder of the Chakri Dynasty, which still reigns over Thailand today. The current king is Rama X who is regarded as the embodiment of Lord Ram and the title of Rama frequently appears in the royal genealogies of Thailand.

The renowned reliefs illustrating about 150 scenes from the Ramakien at Wat Phra Chetuphon (Wat Pho) in Bangkok date back to the early 19th century. Manuscripts and mural paintings illustrating scenes from the Ramakien are particularly famous for their depictions of the monkey armies, with the most notable mural paintings located at the royal temple Wat Phra Kaeo in Bangkok.

In King Rama I’s version of the Ramakien, all names, places, traditions, and flora and fauna were adapted to fit a Thai context. This adaptation transformed the Rama story into a national epic of Thailand, which has gained immense popularity not only as a literary work but also as a traditional mask dance (khon) and even TV dramas. The Ramakien has been republished many times in children’s and juvenile literature, and characters from the Ramayana have appeared on postal stamps and trading cards.

Hinduism in Islamism of Indonesia

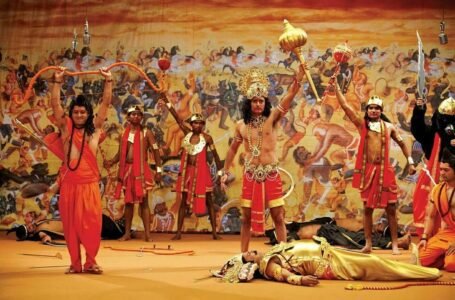

Even though being Muslim nations, the Ramayana has significantly influenced both Indonesia’s and Malaysia’s music, art, and culture. There are other Ramayana adaptations in Indonesia, such as the Javanese “Kakawin Ramayana,” which is the source of the “Balinese Ramakavaca,” another Indonesian rendition of the Ramayana. In Java, the Ramayana is typically presented as a puppet show known as wayang kulit. There are numerous Hindu temples and a predominantly Hindu population on Indonesia’s Bali Island. The performance of Ramlila is performed daily at the Uluwatu temple in their traditional dance style, the Kecak dance, which narrates Sita’s kidnapping and Hanuman’s visit to Ashok Vatika to deliver the Lord Rama’s ring and burn the whole Lanka into a pyre of flames.

The Malay adaptation of the Ramayana, known as ‘Hikayat Seri Rama’ was likely introduced by Tamil traders. The epic was composed between the 13th and 17th centuries. It is written as a ‘Hikayat,’ which means ‘stories’ in Arabic. In Malaysia, the epic’s themes of righteousness, loyalty, and selfless devotion are widely appreciated and Lakshman is celebrated more than Rama for his bravery.

Laos: The City of Lava

Known as ‘Phra Lak Phra Ram’ (or Pha Lak Pha Lam, as modern Lao often replaces R with L), referring to the warrior brothers Lakshmana and Rama, the Ramayana is tremendously consecrated in Laos, believed to be the city of Ram’s son, Lava. Hindu temples, such as Vat Phou in Champassak, are highly revered by the Lao people and are often embellished with scenes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The nation’s epic poem, ‘Phra Lak Phra Ram,’ is adapted from Valmiki’s Ramayana. Sometimes called Phra Ram Sadok (Rama Jataka), it reflects the widespread belief that Rama was a former incarnation of a Buddha-to-be.

Although now a Buddhist country, Laos worships Rama in high regard as the paragon of moral leadership and a true follower of righteousness. The Rama story is stroked in many mural paintings and wood relief carvings on temple doors and windows. The central hall of Wat Oup Muong (underground hall or tunnel) features 29 murals that depict the story. It was also a popular theme in the repertoire of the Lao Royal Ballet until 1975, and this tradition was revived in 2002 by the Royal Ballet Theatre of Luang Prabang. Numerous palm-leaf manuscripts from across Laos contain shorter versions of the Lao Ramayana, Lam Pha Lam, demonstrating the story’s popularity throughout the country, in both urban centres and rural areas. These versions were intended to be sung by Mor Lam, a traditional expert singer who recites lengthy poems and epic literature melodically while accompanied by a Khaen (bamboo mouth organ).

In both Thai and Lao traditions, Hanuman, the leader of the monkey armies, is a favoured Yantra design used by soldiers and martial arts specialists which were often drawn on protective shirts, headbands, battle standards of entire armies, or, most effectively and durably, tattooed on a fighter’s body as Hanuman is considered as the epitome of strength, stamina, agility, intelligence, and devotion.

In Laos, the Ramayana is expressed in five forms: dance, song, painting and sculpture, sacred texts recited during festive occasions, and manuscripts, with their popularity in that order. The Ramayana as a dance-drama holds the highest esteem, performed at the Royal Palace in Luang Prabang and the ‘Natyasala’ dance school in Vientiane, accompanied by appropriate music and song. The Ramayana in painting and sculpture is prominently featured within temples. Its richest forms are found in the court-temples of Luang Prabang, with Ramayana frescoes preserved in Wat Oup Muong.

Ramayan in Cambodia, Nepal, and Myanmar

‘Reamker’ (RamaKerti—Ram + Kirti/glory), dating back to the 16th century, is the Khmer adaptation of the Ramayana popular in Cambodia performed in classical dance-drama and puppet plays. The story revolves around Preah Ream (Ram in Khmer), the abduction of his wife Neang Seda (Sita) by the wicked Reap (Ravan), and her eventual rescue with the assistance of Hanuman. The Angkor Wat temple complex, constructed in the 12th century, includes murals and reliefs depicting the Battle of Lanka from the Ramayana and was initially dedicated to Vishnu. The Reamker has significantly shaped Cambodian arts, including frescoes, shadow plays, and the traditional masked dance drama called lkhon khol. The story is also part of the repertoire of Cambodia’s Royal Ballet.

In Burma, Myanmar, the Ramayana is known as ‘Yama Zatdaw’ and is regarded as a Jataka story in Theravada Buddhism. In this version, Rama is called ‘Yama’ and Sita is referred to as ‘Thida’. It is believed to have been introduced in the 11th century during the reign of King Anawratha. Traditionally it was passed down orally, with the earliest known written version compiled in verse and prose by U Aung Phyo in 1775. The epic’s popularity peaked in the 19th century, featuring lavish performances and stone relief sculptures depicting the saga. The Ramayana made its way into the courts of Burmese kings, with royal troupes of professional artists staging vibrant performances. Even after the decline of the Burmese monarchy, the Ramayana remained beloved and was adapted into classical Burmese drama by ministers such as Myawady Mingyi U Sa. Today, marionette shows and dramatic performances of the Ramayana, known as Yama zat pwe, continue to be popular cultural events in Burma. The influence of the Ramayana extends beyond the performing arts, seen in the motifs and design elements of Burmese lacquerware and wood carvings, reflecting the integration of Hinduism into everyday life.

The oldest manuscript of the Ramayana was found in Nepal which was compiled by Bhanubhakta Acharya and published in 1887.

The Ramayana also transcended into Japan, China, Russia and Mongolia through Buddhist Jataka stories and the legend is known by various names translated into native languages while retaining few Sanskrit and Pali words and performed through traditional classical dance styles.

Spread of Ramayana Outside Asia

In the 19th century, the Ramayana travelled to regions like Africa and the Caribbean through the massive migration of plantation labourers known as girmityas from British India who carried with them Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas, preserving their cultural heritage. Following the abolition of slavery, there was an urgent need for labour on plantations, leading to the relocation of many men and women from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to countries such as Fiji, Mauritius, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Suriname.

A TIMELESS LEGACY

The eternal tale of Ramayana has lived beyond the clutches of time given the timeless wisdom and universal appeal the epic entails. Each character in the story serves as a testament of teachings relevant in today’s reality. The scripture exemplifies valuable morals and the zenith of righteous conduct reflected by the character of Lord Ram who represents India’s unity in diversity and openness of thought. The spiritual text reinforces the victory of good over evil and weaves the rich cultural tapestry of Hinduism. Conclusively, the Ramayana wields remarkable significance in the realm of cultural diplomacy and soft power thereby finely knitting India’s relations with other nations.