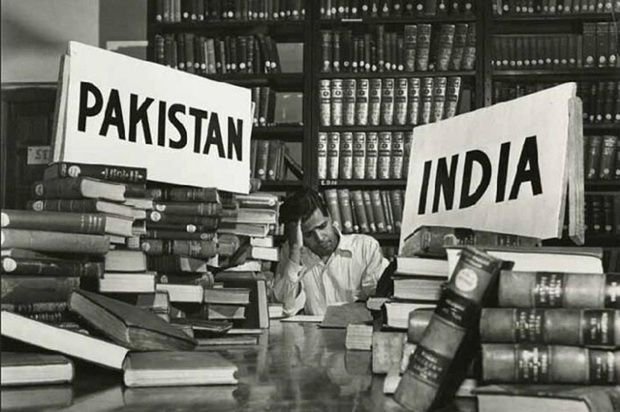

-Vani Mishra When Partition occurred in 1947, the human cost was tremendous. Millions were displaced, families separated, and whole cities rewired overnight by borders slicing through soil and memory both. Amidst this vast disruption, another lesser-known story was unfolding. It was the tale of books—libraries torn out of context, manuscripts destroyed, and whole sets of […]Read More

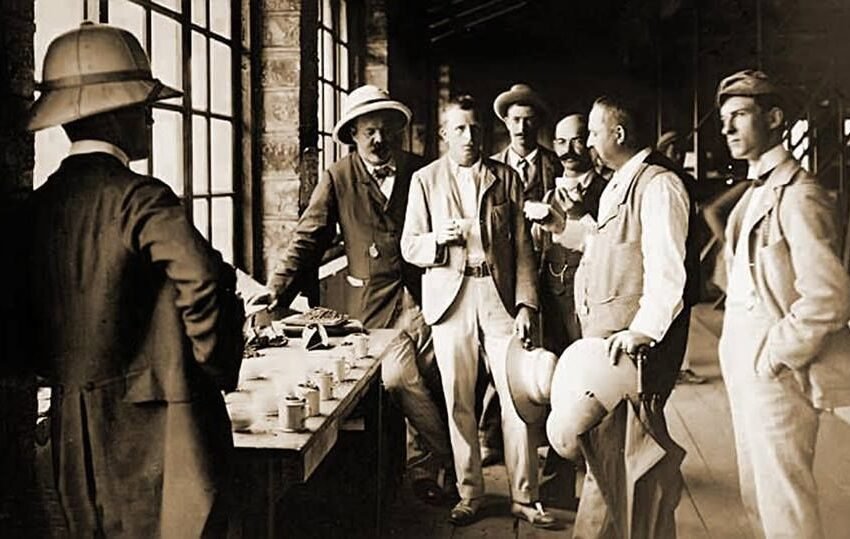

-Vani Mishra There are times in history when the plainest objects bear within them the burden of empires. Tea, that unassuming brew of leaves and water, was one such force. For Britain, it was not just a drink; it was a cultural fixation, a source of vast wealth, and a rationalization for empire itself. For […]Read More

~Vani Mishra To write about India without writing about its railways is simply not possible. The sweet rumble of the train, the iron rails unrolling into the distance, and the crowded platforms thronged with tea vendors and porters are not only a part of travel. They are a part of memory, of identity, and of […]Read More

Kasavu Saree: Weaving Kerala’s Golden Heritage Through Threads of Time

– Bhoomee Vats Used in the border of the saree and not in the saree itself, the term “kasavu” refers to the Zari that is used in the border of the famous Kerala sarees, making it the name of the material which is used in the manufacturing process of the saree. Extending this term, when […]Read More

– Bhoomee Vats India is known for its rich culture and heritage, especially its art, which is rooted in spirituality, mythology, and the country’s history. But it was not until after the modern era that the art of India was reflected on the global stage. Due to this representation, Indian art became the talk of […]Read More

-Vani Mishra History tends to recall freedom in the rhetoric of battles, marches, and slogans. But sometimes the most biting weapon is not a sword or a musket, but the press. In India’s long struggle for independence, newspapers were the pulse of a movement. They were not just ink on paper they were lifelines of […]Read More

-Vani Mishra On a hot summer evening during the late 1930s, as boats anchored in Bombay’s busy harbor, an unusual and intoxicating din drifted out of a club along Marine Drive. The melodies were bright and nimble, the rhythms staccato, the trumpets loud and yet somehow melancholy. It was jazz, the music of improvisation, conceived […]Read More

-Vani Mishra Few things have lived as many lives as the Koh-I-Noor. Its very name, Mountain of Light in Persian, is redolent of both beauty and tragedy. It has gone from hand to hand like a power talisman, coveted not merely for what it was, but for the aura of power it was thought to […]Read More

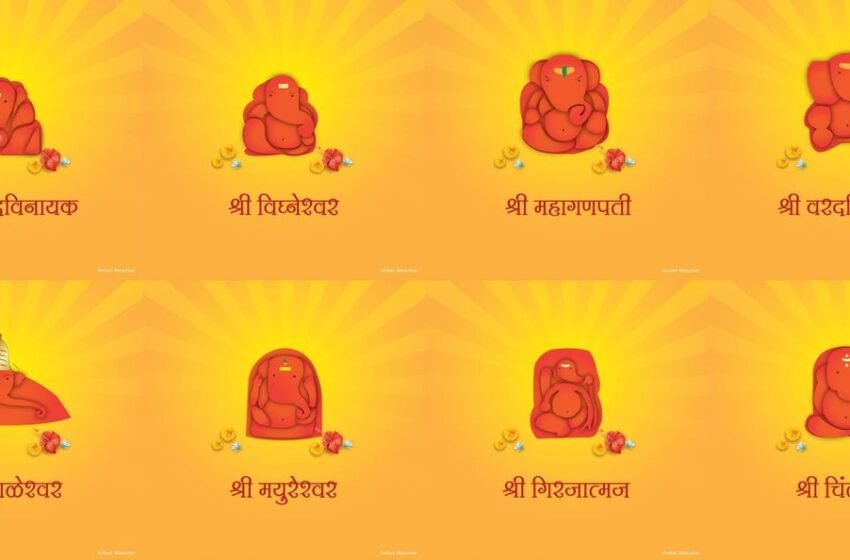

-Bhoomee Vats As all states of India thrive on surplus amounts of temples, Maharashtra, like any other Indian state, is also full of temples where various Gods and Goddesses are worshipped, but one of the most important ones in the state is Ganpati Bappa himself, whose day is celebrated like a brilliant festival itself. The festival […]Read More

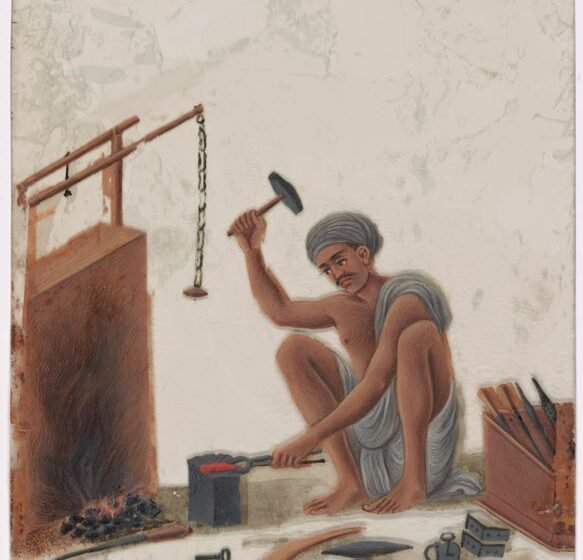

-Bhoomee Vats India holds a huge tradition of metallurgical skills hidden in the pages of history for over 7000 years. Metallurgy is not just a skill or a simple activity for India, but a form of art representing one of the most remarkable achievements of its historical civilizations. It reflects a mastery of science, culture, […]Read More