Exploring the Rich Heritage of Islamic Perfumery: A Journey Through Ittar

In the intricate tapestry of human history, few elements weave together culture, spirituality, and innovation as seamlessly as the tradition of perfumery in Islamic civilization. From the bustling markets of medieval Baghdad to the serene gardens of Al-Andalus, the aroma of exotic fragrances has permeated every facet of life, leaving an indelible mark on society and shaping the olfactory landscape of the world. In this exploration, we delve into the rich history and enduring legacy of Islamic perfumery, tracing its origins, its role in preserving and developing perfumery, cultural significance, and contributions to science and art. From the pioneering innovations of Muslim scholars to the spiritual symbolism of fragrance in Islamic rituals, join us on a fragrant journey through time and culture.

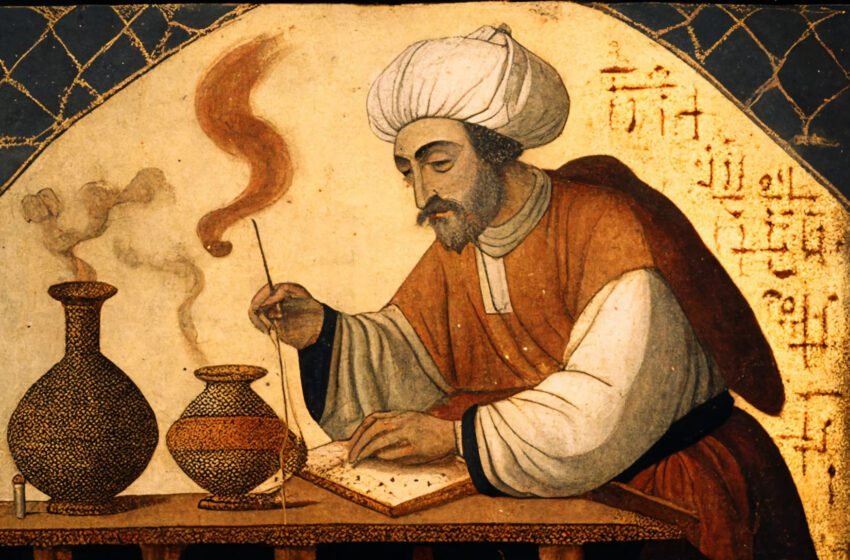

Islamic civilization was a veritable treasure trove of aromatic riches, producing essential oils such as rose, jasmine, and agarwood. Perfumers in the Islamic world were revered for their expertise, developing new extraction and blending techniques to create exquisite fragrances. The Islamic Golden Age, a period of intellectual and artistic flourishing, saw significant advancements in perfumery, with scholars documenting their knowledge in treatises and manuscripts.

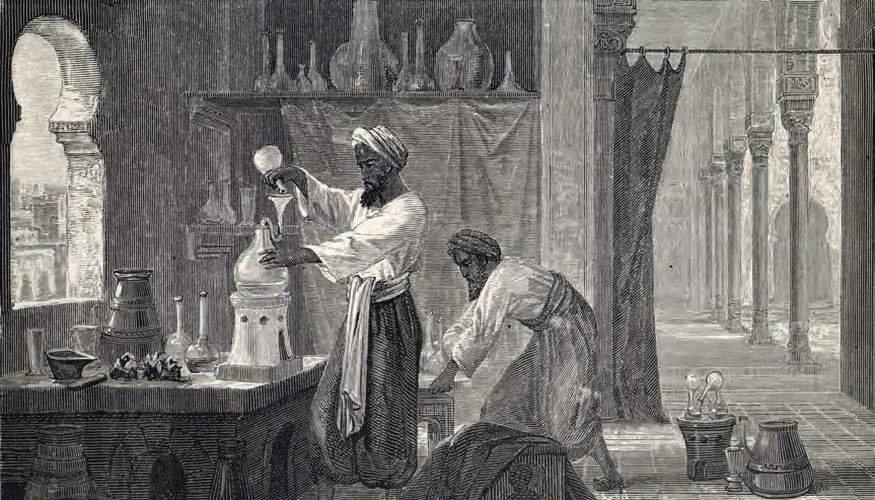

Islamic civilization played a pivotal role in the evolution of perfumery during the Middle Ages. Muslims were among the first to pioneer new methods of extracting essential oils, including the revolutionary steam distillation technique. This innovative process allowed for the extraction of delicate fragrances from flowers, herbs, and spices with unprecedented precision. Additionally, Muslims developed sophisticated methods of preserving essential oils, such as the pickling method, ensuring their longevity and potency.

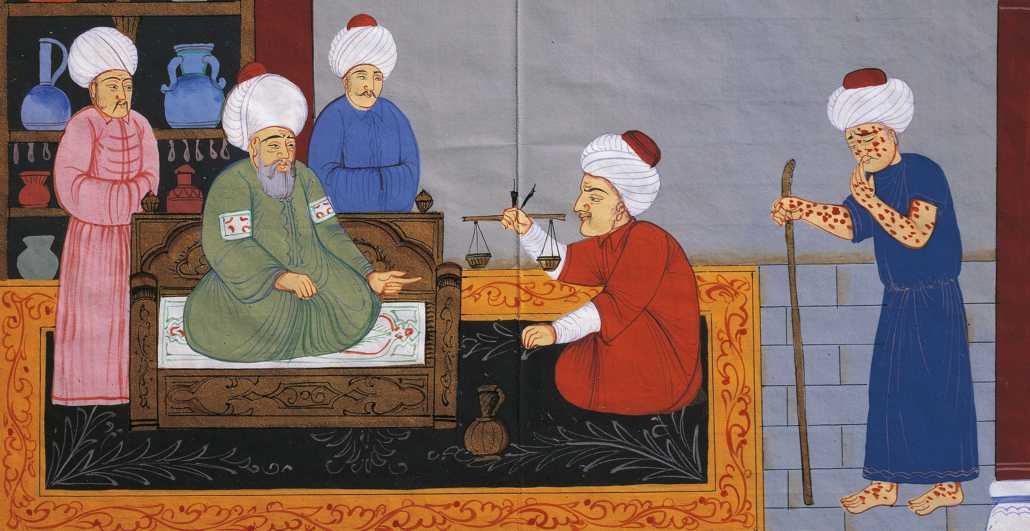

Early chemists in Muslim civilization were engaged in a diverse array of endeavors, ranging from producing rose water to formulating hair dye, soap, and paint. By the middle of the ninth century, these innovators demonstrated an understanding of fundamental chemical processes such as crystallization, oxidation, evaporation, sublimation, and filtration. To ensure the precision of their experiments, they devised accurate scales for weighing chemical substances. Concurrently, they developed novel theoretical frameworks and chemical concepts, some of which endured for centuries.

The scholars of this era made significant contributions to the foundation of the modern chemical industry. Jabir ibn Hayyan also known as “Geber” in the west, and his successor, Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi, were instrumental in developing innovative methods for categorizing substances and systematizing chemical knowledge. They authored textbooks on chemistry and conducted research to enhance ceramic glazes, devise new hair dye formulations, and formulate varnishes for waterproofing fabrics. Additionally, other intellectuals focused on synthesizing chemicals essential for pesticides, paper production, paints, and medicinal applications.

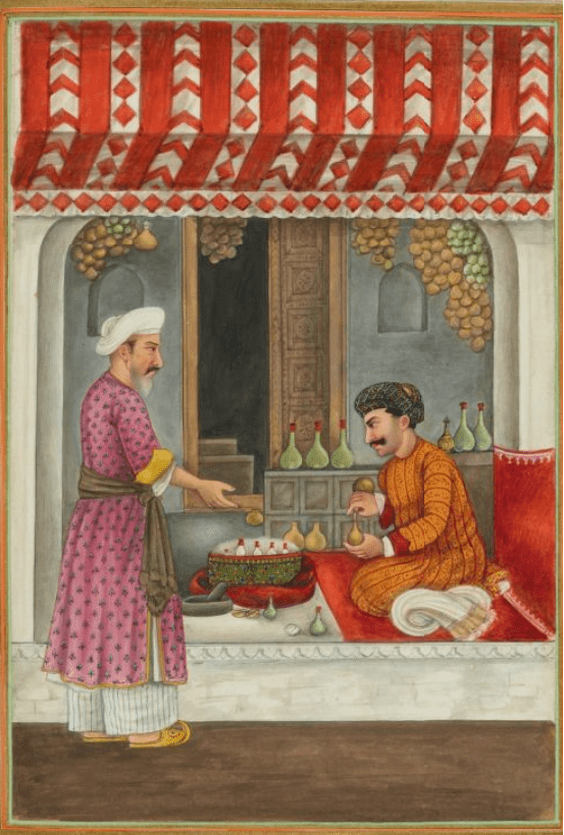

During the 11th and 12th centuries, Arabia facilitated the introduction of musk and floral perfumes to Europe through trade interactions with the Islamic world and returning Crusaders. Individuals engaged in this trade often dealt in various commodities such as spices and dyestuffs. Historical records from as early as 1179 document the Pepperers Guild of London engaging in trade with Muslims, exchanging commodities including spices, perfume ingredients, and dyes.

Perfumes were ubiquitous in Islamic society, serving a multitude of purposes beyond mere adornment. They were integral to religious rituals, symbolizing reverence and purity in worship. Additionally, perfumes were essential for personal hygiene, combating unpleasant odors and keeping the skin soft and supple. In the realm of beauty, perfumes adorned the body, clothing and physical spaces, enhancing allure and elegance. Moreover, perfumes were utilized in medicine, with certain scents believed to possess healing properties for ailments such as headaches and colds. Fragrance was utilized with the belief that it possesses therapeutic qualities beneficial for both physical and spiritual well-being.

Fragrance has always held a sacred place in Islamic culture, deeply rooted in religion and spiritual practices. The Prophet Muhammad himself emphasized the importance of perfumes, declaring them as “the food of paradise.” The Prophet would adorn himself with fragrances during prayers, setting an example for Muslims to follow by wearing perfume when attending Friday prayers. Likewise, the application of scents is promoted during various religious gatherings such as Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. Perfumes were not merely sensory indulgences but pathways to spiritual elevation, enhancing the experience of prayer and meditation. Islamic mystics and scholars expounded on the spiritual symbolism of fragrance, believing that certain scents could elevate consciousness and facilitate communion with the divine.

Furthermore, fragrance plays a significant role in Islamic customs related to hospitality. Visitors are greeted with aromatic water or other pleasant scents, and it is customary to present them with perfumes or scented oils to revitalize themselves after traveling long distances. Across many Islamic societies, the act of offering fragrance is regarded as a gesture of esteem and reverence.

Attar, also referred to as ittar, signifies an essential oil extracted from botanical or other natural origins. Typically, these oils undergo extraction through methods like hydrodistillation or steam distillation. The Persian physician Ibn Sina pioneered the distillation of flower attars. While attar can be synthetically produced, authentic versions are usually distilled using water. These oils are often distilled with a base like sandalwood and then left to mature, a process lasting from one to ten years depending on the desired outcome and botanical ingredients. Essentially, attars are distillations of flowers, herbs, spices, and other natural materials, often over sandalwood oil or liquid paraffins, using hydrodistillation techniques involving specific apparatus like stills and receiving vessels. These traditional methods continue to be practiced in locations such as Kannauj, India. The term ‘attar,’ ‘ittar,’ or ‘itra’ is believed to trace its origins back to the Persian word “itir”, derived from the Arabic term ‘itr,’ meaning ‘perfume.’

The legacy of Islamic perfumery continues to enchant and inspire, shaping the global landscape of scent and beauty. Oud and musk, two beloved fragrances rooted in Islamic tradition, continue to captivate perfume enthusiasts with their timeless allure. The meticulous craftsmanship and artistic sensibility of Islamic perfumery resonate across cultures, reminding us of the enduring power of fragrance to evoke emotions, memories, and transcendence.

Musk constitutes a category of aromatic compounds derived from the glands of mature male Siberian musk deer, a rare species found in the Himalayas. The extraction process involves the killing of the deer, contributing to the endangerment of musk deer species due to high demand. Consequently, synthetic alternatives like ‘white musk’ have emerged. Natural musk is frequently blended with medicines and confectionery, with purported medicinal properties including serving as an antivenom and enhancing organ function.

Agarwood, also known as aloeswood, eaglewood, gharuwood, or the Wood of Gods, is a highly fragrant, dark, and resinous wood utilized in incense, perfume, and intricate hand carvings. Commonly referred to as oud or oudh, derived from the Arabic word “ʿūd,” it holds a revered status in various cultures. Forming within the heartwood of Aquilaria trees following an infection by the Phaeoacremonium mold, agarwood develops as a defensive response. The tree secretes resin to combat the fungal invasion, resulting in a transformation of the heartwood. Initially lacking scent and light in color, the heartwood evolves into a dense, dark, and resin-saturated form as the infection progresses.

Harvested for its aromatic properties, agarwood is renowned in cosmetics under names like oud, oodh, or aguru. With a history spanning thousands of years, oud holds significant value in Middle Eastern and South Asian societies, cherished for its distinct fragrance incorporated into colognes, incense, and perfumes, revered by Muslim, Christian, Hindu, and other religious communities alike. Oud is deeply ingrained within Arab culture as a traditional aromatic and perfume across various forms. Oud also played a pivotal role in the development of trade routes in ancient times within the Arab region. Esteemed by Muslims, oud has been a staple in mosques, where incense chips are ceremoniously burned, adding to the sacred ambiance of religious spaces.

Ambergris, also referred to as Anbar, denotes a waxy substance produced by sperm whales and collected from beaches and the sea. With a musky scent, ambergris has been utilized by humans for over a millennium. Ambrein, an alcohol derived from ambergris, serves as a scent preservative.

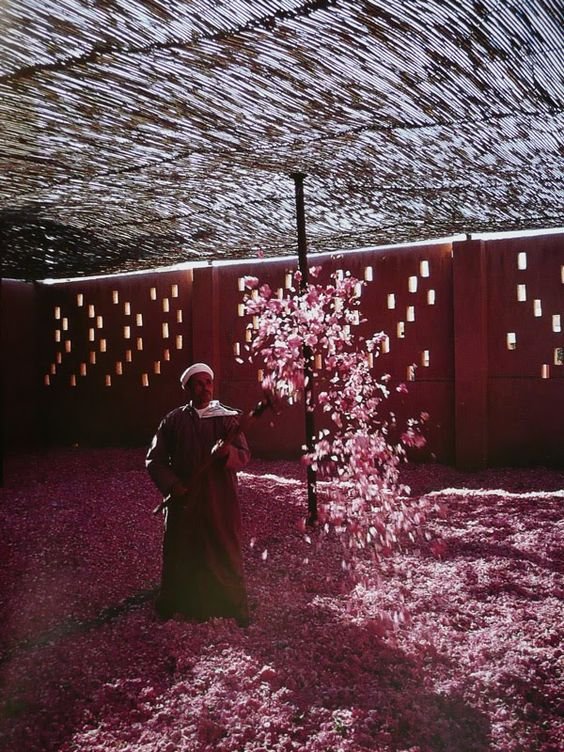

Rose oil, also known as rose otto, attar of rose, or rose essence, refers to the essential oil derived from the petals of diverse rose varieties. The extraction process involves steam distillation for rose ottos and solvent extraction for rose absolutes, with the latter being more prevalent in perfumery. Originating in Greater Iran, this production technique remains prominent despite the availability of organic synthesis, making rose oils one of the most commonly utilized essential oils in perfumery.

In Yemen, Queen Arwa al-Sulayhi introduced a unique variety of attar extracted from mountainous flowers, which she bestowed as a gift to the rulers of Arabia.

Abul Fazal Faizee provides another account of the utilization of attar in crafting the Mabkhara incense burner during the reign of Akbar. He notes that during Akbar’s era, ingredients such as aloe, sandalwood, and cinnamon bark were employed. Additionally, resins like myrrh and frankincense, as well as animal substances such as musk and anbar, were blended with extracts from specific tree roots and various spices. In the realm of Awadh, ruler Ghazi-ud-Din Haidar Shah curated cascades of attar within his chambers, enhancing the ambiance with a continuous infusion of pleasant fragrances, creating a romantic atmosphere.

Attars are commonly categorized based on their perceived effects on the body. During winter, “warm” attars like musk, amber, and saffron are favored as they are believed to elevate body temperature. Conversely, “cool” attars such as rose, jasmine, vetiver (khus), screw pine (kewda), and jasmine sambac (mogra) are preferred during summers for their perceived cooling properties.

The roots of Islamic perfumery run deep, intertwining with the rich tapestry of Islamic history and culture. From the ancient civilizations of Arabia, Persia, and Egypt emerged a vibrant tradition of fragrance, nurtured by the diverse tapestry of Islamic society. Early Islamic scholars and artisans honed their craft, drawing inspiration from the natural world and ancient wisdom to create perfumes of unparalleled beauty and complexity.

Trade and commerce played a crucial role in the spread and refinement of Islamic perfumery. As merchants traversed the vast expanse of the Islamic world, they brought with them exotic spices, herbs, and fragrance materials from distant lands. The bustling markets of cities like Damascus, Cairo, and Baghdad became hubs of perfumery, where artisans and traders converged to exchange knowledge, techniques, and ingredients.

The Islamic Golden Age witnessed a blossoming of scientific inquiry and innovation, with scholars making significant contributions to the field of perfumery. Visionaries like Jabir ibn Hayyan and al-Kindi pioneered new distillation techniques, unlocking the secrets of fragrance extraction and refinement. Their groundbreaking discoveries laid the foundation for modern perfumery, revolutionizing the way we perceive and appreciate scent.

Islamic perfumery exerted a profound influence on the global stage, shaping the olfactory landscape of distant lands. Through trade routes and cultural exchange, Islamic perfumes found their way to Europe, where they captivated the senses of kings, queens, and nobles. The fragrant treasures of the East became coveted luxuries in the courts of medieval Europe, inspiring a burgeoning perfume industry that continues to thrive to this day.

In an era of mass production and synthetic fragrances, the art of Islamic perfumery remains a beacon of authenticity and tradition. Perfumers and artisans continue to uphold the time-honored techniques and craftsmanship passed down through generations, ensuring that the legacy of Islamic perfumery endures. From the bustling souks of Marrakech to the artisan workshops of Istanbul, the spirit of Islamic perfumery lives on, a testament to the enduring power of scent to captivate, inspire, and enchant.

As we conclude our exploration of Islamic perfumery, we are left with a profound appreciation for the depth, richness, and enduring legacy of this timeless tradition. From its humble origins in the bazaars of the Islamic world to its global influence on art, science, and spirituality, perfumery has served as a conduit for cultural exchange, artistic expression, and human connection. As we continue to celebrate and preserve this fragrant heritage, let us be reminded of the profound impact that scent has on our lives, our culture, and our collective memory. In the fragrant tapestry of human experience, Islamic perfumery shines as a beacon of creativity, ingenuity, and spiritual enlightenment, inviting us to savor the essence of life itself.