Heeramandi’s Hidden Gems:The Unsung Heroes of the Indian Freedom Struggle

Heeramandi, translating literally to “diamond market,” is situated in Lahore near the Taxali Gate and Badshahi Mosque. There’s a debate over its naming, with some attributing it to Heera Singh Dogra, son of Dhian Singh Dogra, Prime Minister during Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s reign. It is the subject of the famous Indian writer-director Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s latest cinematic creation. Heeramandi once flourished as a vibrant centre of culture and commerce, its true allure lay in the enigmatic presence of the ‘Tawaifs’, courtesans who were the epitome of refinement, artistry, and elegance reminiscent of royalty. Bhansali, in his 8 episode Netflix series, captures the opulent and dramatic world of the courtesans, touching upon narratives that aren’t mentioned in official Indian history, such as the significant role of the Tawaifs in the Indian Freedom Struggle. Bhansali admits the serialisation of such a vast untapped area was “challenging”, he believed the 8 episode series was the best way to document and do justice to the lives, struggles and efforts of the dynamic and complicated tawaifs.

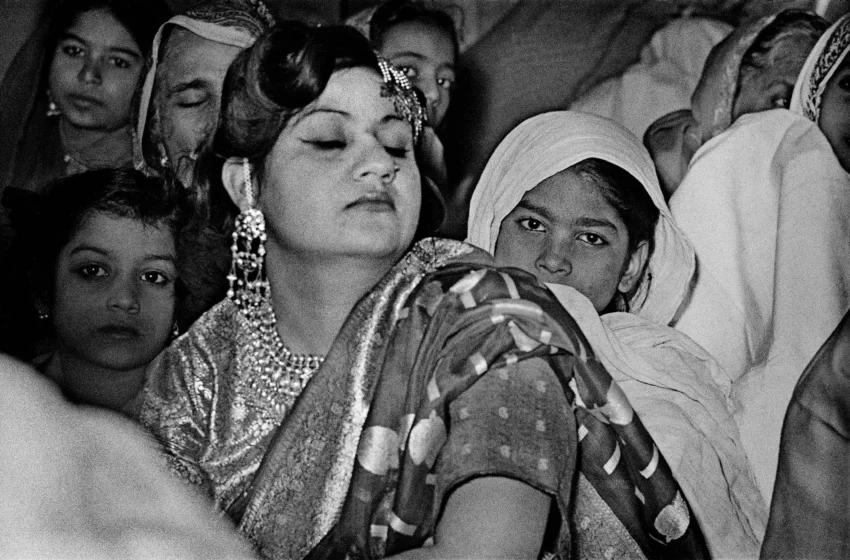

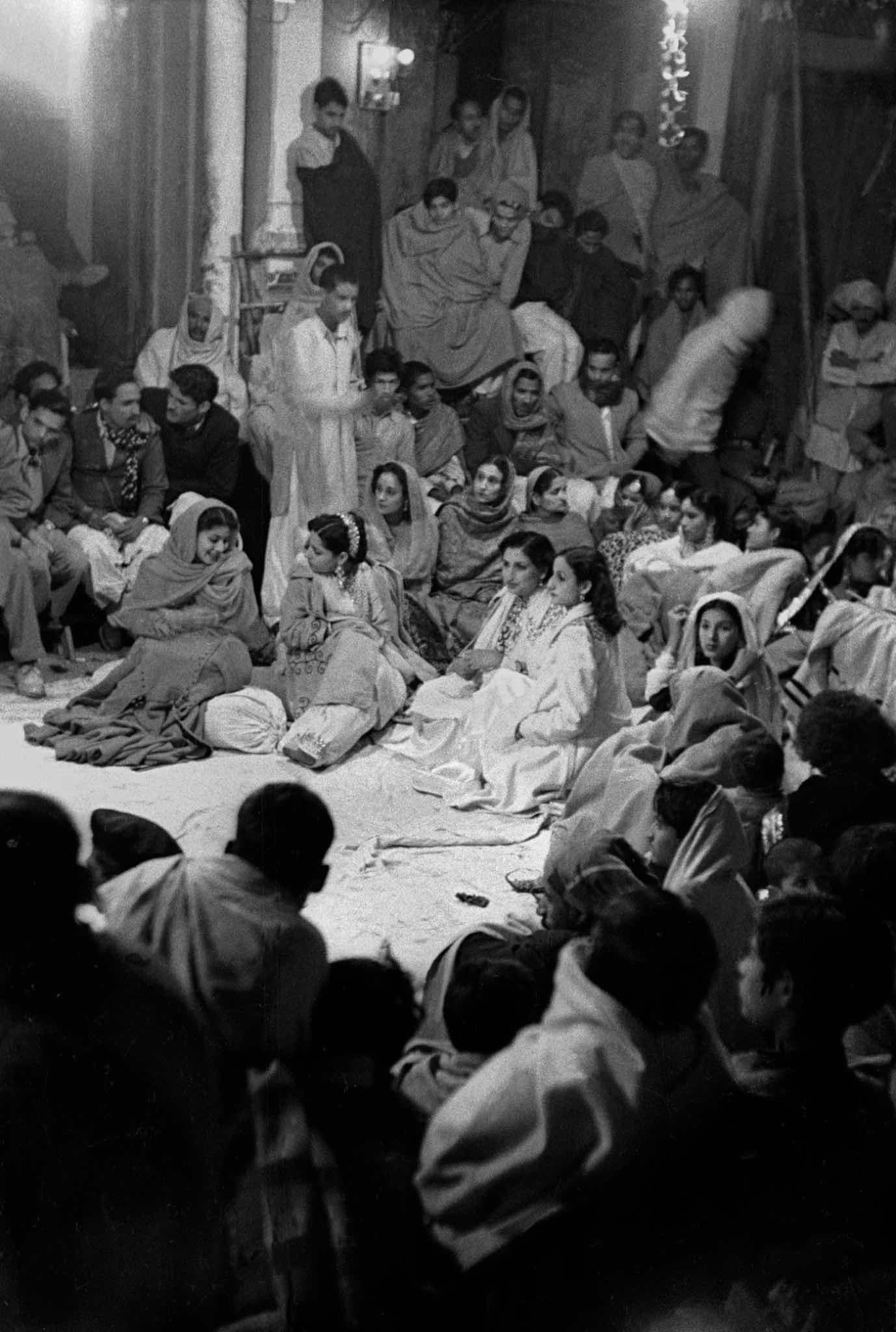

Trained in classical arts like Kathak, Mujra, Thumri, Ghazal, and Dadra, these courtesans wielded influence and wealth, enjoying privileges uncommon for most women of their time. The Tawaifs of Heeramandi were tax-payers in the highest tax-bracket, they had complete rights over their own wealth and property and followed a system of matrilineal inheritance by passing down their profession and wealth to their daughters. They were not merely entertainers but custodians of tradition, preserving and propagating the rich heritage of Indian music and dance. Their ‘kothas’, or residences, were revered as sanctuaries of art and etiquette, where patrons indulged in intellectual discourse and cultural refinement. Nawabs, Princes, other members of the Royal Family and the upper class often visited the courtesans and even sent their heirs to amass an education of the fine arts and learn the “art of conversation”.

The tawaifs were not merely tied to sex work, and it is often debated whether sex work was ever explicitly a major part of their profession; the courtesans, however, enjoyed sexual agency, and such relations between them and their clients were mutually consensual. However, the British Rule and colonialism tarnished the courtesans’ image, reducing them to derogatory labels like ‘nautch girls’ derived from the word ‘naach’, which literally means “dance” or “dancing girls”. The Victorian perspective of the British did not afford tawaifs the same respect they once commanded; instead, they were viewed as promiscuous and morally corrupt. The colonial lens reduced these custodians of education, heritage and culture to mere “prostitutes”. The transition from revered artists to marginalised figures was swift, as British morality projects equated public performers with prostitutes, branding their ‘kothas’ as brothels.

Under British rule, Heeramandi transformed from a haven of art to a den of exploitation, with brothels proliferating to cater to British soldiers. The decline of the tawaif culture accelerated during Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq’s era, marked by a crackdown on music and dance establishments associated with prostitution. The once-thriving hub of art and culture now stood silent, echoing the lost grandeur of the tawaif culture.

Despite facing oppression and the threat of extinction, tawaifs played significant roles in India’s struggle for independence. They were among the wealthiest members of society and religiously donated their wealth to the freedom and rebellious movements. The tawaifs provided refuge and support to rebels during the 1857 uprising against British rule and actively participated in movements led by Mahatma Gandhi, such as the non-cooperation movement. Their contributions, both financial and ideological, underscored their resilience and patriotism.

The stories of these courageous courtesans often remain overshadowed by the deeds of male leaders during the struggle for independence. There exist numerous remarkable contributions from tawaifs who defied societal norms to become pivotal figures in the quest for freedom.

Azeezun Nisa also known as Azeezunbai, a native of Lucknow who later settled in Kanpur, emerged as a prominent figure in the 1857 uprising against the British East India Company. Azeezunbai spent her life in Kanpur, where she pursued a career as a courtesan. Her life journey reflects a series of calculated choices, showcasing her adept strategic abilities. Azeezunbai gained widespread attention for her well-known romantic liaison with Shamsuddin Sawar of the 42nd Cavalry, which likely spurred her participation in the Revolt of 1857. Clad in male attire and armed with pistols, she fearlessly led and inspired sepoys. She had assembled a fearless group of women who travelled around, offering encouragement to the soldiers, tending to their injuries, and distributing weapons and supplies. Her house became a strategic hub for rebels, solidifying her status as an integral figure in the struggle for independence.

Another notable tawaif of the time was Hussaini of Kanpur (then, Cawnpore), whose involvement in the Bibighar massacre which led to the deaths of around 100 British women and children, underscored the depth of engagement some courtesans had in the rebellion. Believed to be one of the chief conspirators, Hussaini’s actions epitomised the significant role played by tawaifs in challenging colonial rule.

Begum Hazrat Mahal, formerly a courtesan, is revered primarily as the wife of Wajid Ali Shah, Nawab of Awadh; she rose to prominence for her leadership during the 1857 revolt. Following her husband’s exile to Calcutta and the eruption of the Indian Rebellion, she appointed her son, Prince Birjis Qadr, as the ruler of Awadh, serving as regent during his youth. However, she was compelled to relinquish this position after a brief tenure. Eventually seeking refuge in Nepal via Hallaur, she passed away in 1879. Her involvement in the rebellion has cemented her status as a heroine in India’s post-colonial history. She seized control of Lucknow after her husband’s exile, briefly reinstating Indian rule in the region. Her unwavering resolve and strategic acumen made her a symbol of resistance against British oppression.

In the early 20th century, Gauhar Jaan, a celebrated courtesan considered amongst the richest women in India at the time – a ‘crorepati (millionaire), lent her voice to the Swaraj movement at the behest of Mahatma Gandhi. Gauhar Jaan requested the presence of Gandhi at her fundraising concert, however due to political and rebellious developments he was unable to attend and instead sent a representative to collect the money. Due to Gandhi’s absence, Gauhar Jaan contributed only half of the funds raised in the concert. Despite her unconventional behaviour, she remains a significant figure of the freedom struggle, embodying the spirit of support and autonomy prevalent among tawaifs of her time.

Similarly, Husna Bai’s leadership of the Tawaif Sabha in Varanasi during the non-cooperation movement showcased the collective efforts of tawaifs in supporting the independence struggle. Husna Jan, also known as Husna Bai, was a Tawaif and Thumri vocalist from Banaras in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. She was renowned in Uttar Pradesh for her mastery in Khayal, Thumri, and Tappa singing styles. Under her guidance, the tawaifs protested by wearing iron shackles instead of ornaments and boycotting foreign goods, highlighting their solidarity and commitment to the cause.

Vidyadhar Bai, inspired by Gandhi’s ideals, used her talent as a singer to rally support for independence. She decided to solely perform nationalist songs in her ‘mehfils’ or gatherings, and boycotted foreign-made clothing. Vidyadhar Bai wore exclusively Indian hand-spun ‘khaadi’ clothes and encouraged those around her to do the same, she exemplified the pivotal role of art and culture in galvanising the masses towards freedom.

The British crackdown on the courtesans of Heeramandi intensified once the patriotic and anti-colonial movements and efforts of the tawaifs became known. Imperial forces physically destroyed kothas, obtained warrants to search the residences and proceeded to demolish them, smashing furniture and tearing down curtains. Further, the British forces lay claim on the courtesans’ wealth, jewellery, and properties. They dismantled the tawaif culture morally by imposing Victorian morality and degrading the position and work of the tawaifs. It is quite telling of the influence of British imposed moral standards on Indian society that even the remaining respected courtesans, who significantly contributed to the economy, supported the freedom movement, and were significant taxpayers, were compelled into prostitution for their livelihood. The once opulent, respected and culturally significant Heeramandi became a Red Light Area, with the Tawaifs being forced into sex work by British officers. Although trained in music, it is reported that the tawaifs were also denied jobs at All India Radio or any other respected organisation.

Yet, the tawaifs’ legacy endures through tales of defiance and courage, exemplified by figures like Gauhar Jaan, Azeezunbai and Husna Bai, whose contributions to the Swaraj fund and support of various freedom movements highlighted the courtesans’ enduring spirit amidst adversity.

The narrative of tawaifs unveils a complex tapestry of art, politics, and societal norms. Their story challenges stereotypes and sheds light on the untold chapters of India’s history. In conclusion, the stories of Azeezunbai, Hussaini, Begum Hazrat Mahal, Gauhar Jaan, Husna Bai, and Vidyadhar Bai serve as testament to the indomitable spirit and invaluable contributions of tawaifs in India’s struggle for independence. Despite facing adversity and oppression, these remarkable women left an indelible mark on history, challenging stereotypes and reshaping the narrative of India’s quest for freedom.

As Heeramandi fades into obscurity, its transformation into a bustling market mirrors the erasure of its cultural past. Yet, the echoes of tawaifs’ melodies and the resonance of their activism linger, reminding us of their enduring legacy in shaping India’s identity and struggle for independence. Heeramandi, once a symbol of opulence and refinement, now serves as a poignant reminder of the resilience and contributions of tawaifs to India’s cultural heritage and struggle for independence.