The Indus Script: A Lost Bronze-Age Cipher

~ Debashri Mandal

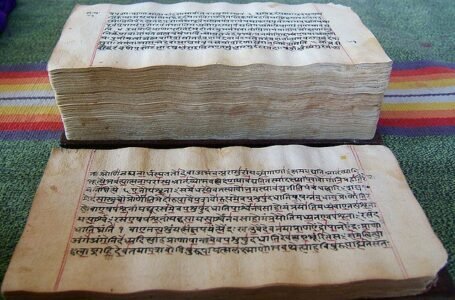

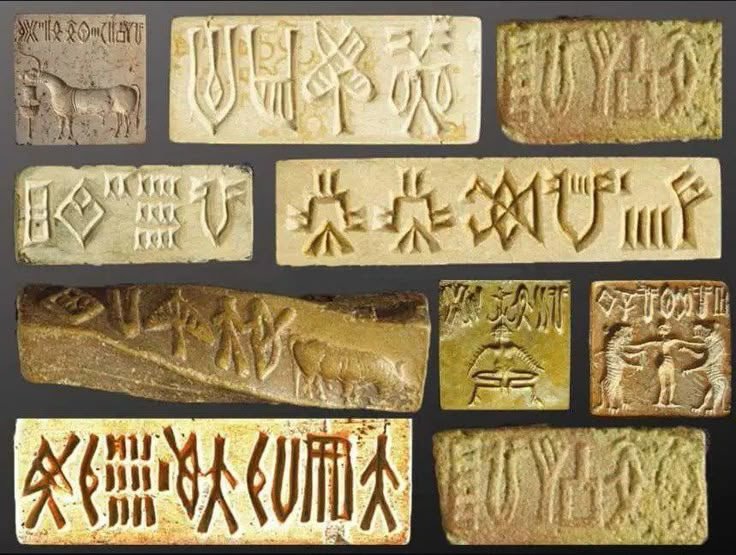

In 1872, British surveyor Alexander Cunningham uncovered a small clay seal at the ruins of Harappa. It showed a deeply incised bull (no hump) facing right, and above it six short symbols that he could not recognize as any known Indian script. “They are certainly not Indian letters,” Cunningham wrote – he concluded the object must be foreign. Over the next century, archaeologists found thousands more such seals and tablets across the Indus Valley. Most depict animals (the famous one-horned “unicorn,” rhinos, elephants, etc.) alongside strings of characters. For example, one typical stamp seal shows a zebu bull next to a five-character inscription (image below). Even as trade goods and monuments of the Harappan cities are slowly interpreted, the meaning of those tiny inscriptions eludes us.

Seal impression with a zebu bull and five Indus signs. The Indus script appears almost exclusively on small seals, tablets, and pottery fragments, usually with only a few symbols.

By recent counts, archaeologists have now recovered roughly 4,000–5,000 inscribed objects from Harappan sites (and even a few as far away as Mesopotamia). These inscriptions are extremely brief – typically 2–5 signs long – and show little change over the millennium (c. 2600–1900 BCE) in which they were used. The brevity is striking: most texts fit on a tiny seal or pottery shard. There is no long Indus document or bilingual key (like a Rosetta Stone) to help with translation. As one scholar notes, “the brevity of the inscriptions, along with the absence of a Rosetta Stone–like text showing [their] symbols in translation, are among the reasons the script has not been deciphered”.

Artifacts: Seals, Tablets, and the Dholavira “Signboard”

Most Indus script evidence comes from stamp seals carved in steatite or ivory. These were likely used to stamp clay on packages or to seal documents. Each seal often bears an animal figure (unicorn, bull, elephant, rhinoceros, or a mythic beast) and a short line of script. For example, Cunningham’s 1872 Harappa seal had a bull with two stars under its belly, and six symbols above (see replica), and modern excavations have turned up hundreds of similar seals. In fact, about 90% of known Indus seals come from sites along the Indus River in today’s Pakistan, with the rest in India and a few in regions like Iraq. Contemporary reports suggest the seals were used as labels or markers of trade (“little masterpieces of controlled realism”), but what the inscriptions say remains unknown.

Besides seals, short graffiti appear on pottery, copper tablets, and other objects. The average inscription is under a dozen signs – very unlike the long texts of Mesopotamia or Egypt. Intriguingly, one of the longest Indus texts was discovered outside the major cities. At Dholavira (in Gujarat), excavators found a wooden “signboard” about 3 meters long, with 10 large Indus symbols inlaid in white gypsum. (One symbol repeats four times.) The board likely hung over a city gate. Yet even this extraordinary inscription – by far the lengthiest known – is still indecipherable. As one archaeologist put it, “until the Indus script is deciphered, what the sign is saying remains a mystery”.

Dholavira “signboard” from ca. 2400 BCE: ten large Indus symbols (inlaid white gypsum) span a wooden plaque at the city gate. This is one of the longest Indus inscriptions known. Even so, its meaning is unknown without decipherment.

Why It’s So Hard: Brief Texts and No Rosetta Stone

Deciphering any ancient script relies on context, parallels, or bilingual texts. The Indus case lacks all of these. First, the inscriptions are very short, usually just a few signs. This makes it impossible to look for repeated phrases or grammatical errors in isolation. Second, no bilingual inscription is known. Unlike Egyptian hieroglyphs (with the Rosetta Stone) or the Hittite tablets with Akkadian, we have found nothing that shows the same text in Indus script alongside a known language. Third, and perhaps crucially, the underlying language is unknown. We do not have any clear candidate for what language these symbols encode (Proto-Dravidian? Early Indo-Aryan? Munda or something else?), nor do we know of any descendant language. Without knowing the language family or having a “pronunciation key,” even a string of signs can only be studied statistically or pictorially. In fact, researchers have noted that the Indus script shows no significant changes over its use and no repeated long texts, which compounds the difficulty.

In short, “most crucially, we don’t know what other language it may be related to,” making a decipherment algorithm like those used for other scripts inapplicable to Indus. Computer scientist Jiaming Luo of MIT remarked that Luo’s statistical model (successful on Linear B or Ugaritic) simply “wouldn’t work for the Indus script” because of this uncertainty. The result is that centuries of inscriptions remain silent – and many scholars have tried (and failed) to coax meaning from them.

Scholarly Theories and Attempts

Despite these challenges, many researchers have proposed interpretations. Broadly, these fall into two camps: those who believe the script encodes a spoken language, and a minority who suspect it might be non-linguistic symbols only. We will touch on the main linguistic hypotheses (most notably Dravidian) and the alternative view.

Dravidian Hypothesis

A prominent theory is that the Harappan language was a form of Dravidian (a family that today includes Tamil, Telugu, etc.). This was championed early on by Asko Parpola and Iravatham Mahadevan, and supported by others. Parpola (1994) and colleagues noted that the Indus script is logo-syllabic (like Dravidian scripts) and that certain signs can be read by rebus, using a sign’s picture and a Dravidian word sounding alike. For example, a common symbol depicts a fish, and the Proto-Dravidian word “meen” means both fish and star. Parpola suggested that in some inscriptions the fish sign was meant to represent “meen” (fish) or “star” interchangeably【15†L53-60】. In 2011, a computational study by Rajesh P. N. Rao et al. (USC) found that the Indus scripts’ symbol sequences have statistical properties (conditional entropy) very similar to those of Old Tamil. In other words, the Indus writing behaves more like a structured language (similar to Tamil) than like a random or symbolic code.

Iravatham Mahadevan identified recurring clusters of signs as well. In 2014, he tentatively read one four-sign sequence as “merchant of the city” in a Dravidian language. He stressed this was not a full decipherment, but he believed it supported the idea of a Dravidian Harappan. Archaeologist Walter Fairservis likewise argued (on linguistic and iconographic grounds) that the scripts likely recorded names or titles, using animal figures as tribal totems or clan symbols. Taken together, these efforts have made the Dravidian hypothesis a leading contender: many scholars feel the Indus language “most likely belonged to the Dravidian family”. However, no consensus reading of the script has emerged.

Other Language Theories

Some have proposed that the Indus language was an early Indo-Aryan (Sanskritic) tongue. The 1970s–80s claims of S.R. Rao and others tried to link symbols to Sanskrit/Phoenician letters, but these readings have been widely questioned. Critics note that key Indo-European features (like grammatical affixes or evidence of horses) seem absent in the Indus corpus. A less popular suggestion is that the script encodes a Munda (Austroasiatic) language. This too has few advocates, largely because the known Munda vocabulary for the Harappan era does not match the archaeological culture. In short, while many specific decipherments have been claimed, none have won broad acceptance outside small groups of enthusiasts.

Non-Linguistic Symbol Theory

Not all scholars insist the Indus signs form a language. In 2004, a group of Harvard researchers (Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel) controversially argued that the Indus “script” might be nonlinguistic – essentially a collection of symbols (perhaps ritual or clan emblems) rather than true writing. They even offered a reward for finding an inscription over 50 symbols long, to disprove their claim. Most Indologists and Indus specialists rejected this view, pointing to patterns and repeated sequences that suggest linguistic structure. Subsequent quantitative work (discussed below) has generally supported the idea that the inscriptions encode a language of some kind.

For now, the mainstream view remains that the Harappans had a real language. But without more clues, the specific tongue is still debated. In recent years new computational techniques have been brought to bear in hope of breaking the logjam.

Computational and AI Approaches

Modern computer science offers powerful tools to analyse the Indus script’s structure, even if it can’t directly translate it. One landmark study (Cambridge, 2019) took all ~4,000 inscriptions and applied an information-theoretic approach. They computed the entropy of sign sequences: in linguistic writing, certain symbol combinations are more predictable (for example, in English “qu” always appears together). By contrast, random symbols or DNA have very high entropy (near-random distribution). The researchers found that the Indus inscriptions cluster with known languages (and far below purely random or genetic sequences). In fact, on an entropy graph the Indus data fell just below Sanskrit and aligned closely with Tamil texts. One team member recalls “It felt fantastic… Yes, we’ve really got something here,” interpreting this result as evidence that the script has linguistic organization. In short, mathematical analysis shows the Indus sign sequences look more like writing than like random symbols or code.

Parallel work has used neural networks and pattern recognition. Debasis Mitra (Florida Tech) has led an effort to digitize the Indus corpus from images. His team compiled over 1,000 photographs of seal impressions, then trained a two-stage convolutional neural network to detect individual Indus graphemes. The result: about 88% accuracy in recognizing symbols on seals. This “automated script recognition” system extracts the symbol sequences and stores them in a database for analysis. Similarly, a recent peer-reviewed project (Dixit et al., 2025) developed an end-to-end AI pipeline: two deep-learning models read the sequence of Indus characters on a seal image, and a third model identifies the animal or motif. In essence, these tools perform a kind of OCR (optical character recognition) for the Indus script, vastly speeding up what used to be a laborious manual task. They can feed into statistical studies and pattern searches (for example, spotting repeated phrases or grammatical markers) on the growing digital corpus.

Recent AI work on the Indus script. Left: an automated pipeline (ASR-net) uses deep learning to extract symbol sequences from seal images, storing them in a database. Right: Florida Tech’s system uses convolutional neural networks to identify individual Indus graphemes from photographs, achieving ~88% detection accuracy.

These efforts, while promising, have limits. The total Indus dataset is small (a few thousand texts), so “big data” style machine learning is hard. As one researcher noted, if the script is largely pictorial or ideographic, a blind AI might miss its deeper meaning. Another Harappan student commented that AI alone cannot be expected to grasp symbolic nuances (“How will AI know these symbols represent the fragments of Horus’ eye?”). Thus, the role of AI is seen as assisting human scholars – rapidly cataloguing signs, proposing statistical patterns, and testing hypotheses – rather than doing the translation by itself. Nonetheless, these digital archives and algorithms are making the corpus far more searchable and better understood than ever before.

Conclusion: Waiting for a Breakthrough

The Indus script remains one of the great unsolved puzzles of archaeology. We have come a long way from Cunningham’s note of bewilderment, but the core mystery persists. As one scholar put it, deciphering the script could finally move the Indus civilization “from prehistory into history,” shedding light on who these people were and what they thought. To encourage progress, even civic leaders are taking note: in 2025, the government of Tamil Nadu announced a $1 million prize for anyone who can crack the Indus code. In parallel, teams of linguists, historians, and computer scientists continue to push forward – refining databases of symbols, running AI models, and comparing patterns across ancient languages.

What will it take for a breakthrough? Possibly a new archaeological find – a longer inscription or an unexpected bilingual text – that gives a Rosetta Stone–style clue. Or perhaps a clever insight that finally ties the script unambiguously to a known language family. Until then, the story of the Indus script is a story of patient detective work. Its brevity and obscurity make it frustratingly resistant, but each new line of code, each computational hint, brings us a tiny step closer to hearing the voice of the Harappans.