The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE): Empire, Ideology, and the Crisis of the Greek World

-Prachurya Ghosh

The Peloponnesian War stands as one of the most consequential conflicts in ancient history, not only for its scale and duration but also for the depth of political, social, and philosophical reflection it generated. Lasting nearly three decades, the war involved most of the Greek city-states and fundamentally reshaped the structure of Greek civilization. It marked the end of the so-called Golden Age of Athens and revealed the internal contradictions of the classical polis system. More than a struggle for territorial dominance, the war represented a conflict between two competing models of political organization: the imperial democracy of Athens and the militarized oligarchy of Sparta.

The war is primarily known through the work of Thucydides, whose History of the Peloponnesian War is regarded as the first truly critical historical account in Western literature. Unlike earlier historians, Thucydides rejected mythological explanations and focused instead on rational analysis, power relations, and human motivations. His work makes the Peloponnesian War not merely a historical event but a theoretical case study of politics and international relations.

The Greek World Before the War

Before the outbreak of hostilities, the Greek world was organized into a loose network of independent city-states, or poleis, each with its own political system, economy, and military organization. These city-states were united culturally by language, religion, and shared traditions, but they were fiercely independent and often hostile to one another.

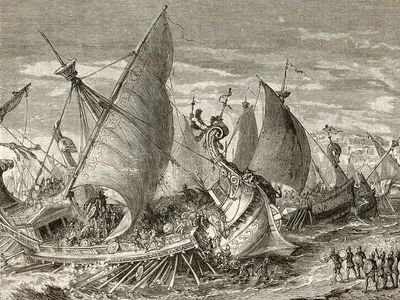

The Persian Wars in the early fifth century BCE had temporarily united the Greeks against a common enemy. However, victory over Persia did not produce lasting unity. Instead, it created a power vacuum. Athens, having developed the largest navy, assumed leadership of the Delian League, while Sparta remained the dominant land power through its leadership of the Peloponnesian League. Over time, these two alliances became rival blocs, dividing the Greek world into opposing camps.

Athenian Imperialism and Spartan Fear

Athens gradually transformed the Delian League into a maritime empire. Member states were required to pay tribute, which financed massive building projects in Athens, including the Parthenon. Revolts were brutally suppressed, and political autonomy was steadily eroded. Although Athens justified its actions as necessary for collective security, in practice the empire served Athenian economic and strategic interests.

Sparta viewed these developments with deep anxiety. Its own society depended on the control of the helots, a large population of enslaved agricultural workers. Any instability in the Greek world could encourage rebellion at home. The expansion of Athenian power thus appeared as an existential threat. Thucydides’ famous formulation captures this structural tension: the real cause of the war was the growth of Athenian power and the fear it inspired in Sparta.

Ideological Conflict and Civil Strife

The Peloponnesian War was also an ideological struggle. Athens represented democratic governance, commercial wealth, and cultural innovation. Sparta embodied oligarchic rule, austerity, and military discipline. These contrasting models generated political polarization across the Greek world. Cities aligned with Athens often adopted democratic constitutions, while those allied with Sparta tended toward oligarchy.

This ideological division frequently produced internal conflicts. Civil wars erupted within city-states as democratic and oligarchic factions sought external support. These conflicts were often marked by extreme violence, betrayals, and mass executions. Thucydides famously described how language itself was corrupted during the war, with moral concepts redefined to justify brutality and ambition.

The Failure of Strategy and the Human Cost

The early years of the war revealed the limits of rational planning. Pericles’ defensive strategy sought to avoid major land battles and rely on naval superiority. While logically sound, it produced catastrophic social consequences. The overcrowding of Athens led to the outbreak of plague, which killed tens of thousands and shattered public confidence in political leadership.

The psychological effects were profound. Religious belief weakened, traditional social bonds eroded, and individual survival replaced civic duty as the primary concern. The plague demonstrated that even the most carefully designed political systems were vulnerable to unpredictable forces.

The Sicilian Disaster and Democratic Failure

The Sicilian Expedition represented the height of Athenian imperial ambition and the depth of its political misjudgment. The campaign was approved through democratic decision-making, yet it was driven by popular enthusiasm rather than strategic necessity. The result was one of the greatest military disasters in ancient history.

This episode exposed a fundamental weakness of democratic politics in wartime: the tendency for collective emotions to override rational analysis. The destruction of the Athenian expeditionary force undermined the empire and revealed the dangers of unchecked popular power.

Persia and the End of Greek Autonomy

In the final phase of the war, both sides abandoned earlier principles. Sparta allied with Persia, the former enemy of Greek freedom, in exchange for financial support. This alliance symbolized the collapse of the ideals that had once united the Greeks. Independence was sacrificed for short-term advantage.

Athens, weakened by economic exhaustion and internal revolts, could no longer sustain resistance. Its final defeat marked not only the end of the war but also the end of the classical Greek balance of power.

Cultural and Philosophical Legacy

The cultural consequences of the war were immense. Greek tragedy, philosophy, and historiography increasingly focused on themes of suffering, moral ambiguity, and the limits of human reason. Thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle developed their political theories in a world shaped by the memory of systemic collapse.

Thucydides’ work remains the most enduring intellectual legacy of the war. His analysis of power, fear, and self-interest laid the foundations for modern political realism. The Peloponnesian War thus became not merely a historical event but a model for understanding political conflict in all periods.

Conclusion

The Peloponnesian War was not simply a war between two cities; it was a civil war of an entire civilization. It exposed the contradictions of empire, the fragility of democratic institutions, and the destructive logic of power politics. The war ended the classical Greek world and inaugurated a period of instability that eventually led to foreign domination. Its significance lies not only in what it destroyed but in what it revealed about the enduring patterns of human behavior in times of crisis.