A Gem’s Odyssey: The Fascinating Voyage of the Koh-i-Noor Across Continents

In 1739, Nadir Shah of Persia orchestrated an invasion of India that was marked by brutal plunder, including the sack of Delhi. After a decisive victory over the Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah, he laid claim to the rich treasures of India like the Timur Ruby and Daria-e-Noor. But it was when he laid his eyes on the grandest diamond of them all, that he exclaimed “Koh-i-Noor !” (Persian for Mountain of Light). Truly, this reaction was completely justified since at that point in history, the Koh-i-noor was the largest diamond to exist, weighing at an unbelievable 186 carats.

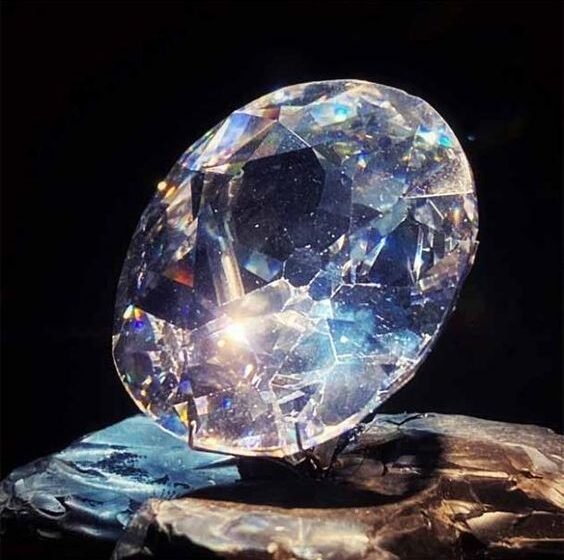

The Koh-i-noor has been a diamond that has attracted the desires of numerous Kings and Emperors. Mined in India, its origins are shrouded in legend and myth, with records tracing its existence as far back as 1304. The diamond passed through numerous hands, including Indian rulers, Persian and Afghan conquerors, and eventually found its way to the British Crown. The Kohinoor diamond is a breathtaking gemstone renowned for its remarkable size, clarity, and rich history. This oval-cut diamond exhibits a stunning colorless transparency, allowing light to refract and sparkle brilliantly from its facets.

The Kohinoor’s allure lies not only in its impressive size and clarity but also in the legends and lore surrounding it. Believed by some to carry a curse for its tumultuous history, the diamond has been part of royal treasures, symbolizing power, wealth, and sovereignty. Today, the Kohinoor remains a prized jewel in the British Crown Jewels, displayed in the Tower of London. However, calls for its return to India persist, echoing sentiments of restitution and cultural heritage preservation. Its legacy endures as a testament to the complex intersections of colonialism, conquest, and the enduring allure of precious gems. Its enduring appeal continues to captivate the imagination of admirers worldwide, serving as a timeless emblem of human ingenuity and the enduring allure of precious gemstones.

Ancient sources point to the Golconda Diamond mines as the possible birthplace of the Kohinoor diamond. The Golconda diamond mines, located in the present-day state of Telangana, India, hold a legendary status in the world of gemstones. Dating back to at least the 4th century BCE, these mines were renowned for producing some of the most exceptional diamonds known to history. It was during the rule of the Kakatiya dynasty (12th-14th centuries CE) that systematic diamond mining began in Golconda. Golconda’s prominence in the diamond trade continued through the medieval and early modern periods, reaching its zenith during the rule of the Qutb Shahi dynasty (16th-17th centuries CE). Along with the Koh-i-noor, the Hope Diamond and the Darya-i-Noor are also believed to have been mined here.

The first historical mention of the Koh-i-noor is found in Alauddin Khilji’s diary. He talks about acquiring the huge diamond from the rich lands of the Kakatiya kingdom in the South. The Kakatiya dynasty, ruling over the Deccan region of southern India, possessed immense wealth and influence, including control over the famed Golconda diamond mines. Alauddin Khilji, hearing of the Kakatiya’s riches, launched a series of military expeditions into the Deccan. His armies marched southward, conquering territories and subjugating rival rulers along the way. The exact circumstances of how Alauddin Khilji acquired the Kohinoor from the Kakatiyas are shrouded in mystery. Some accounts suggest that it was seized as spoils of war during the Sultan’s conquests, while others propose that it was obtained through diplomatic negotiations or as tribute payments.

Regardless, it is believed the Koh-i-noor was then transferred from one Sultan to another and eventually came in the possession of Babur as his victory prize over the Lodhis. In 1526, Babur, a descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan, defeated Ibrahim Lodhi, the last Sultan of Delhi, in the pivotal Battle of Panipat. He writes in his accounts how he received in tribute a “famous” diamond whose weight was nearly 187 carats. Its acquisition further solidified Babur’s authority and symbolized the wealth and prestige of the Mughal dynasty.

Under subsequent Mughal rulers, including Babur’s descendants such as Akbar the Great and Shah Jahan, the Kohinoor remained a cherished jewel of the imperial treasury. It was often worn by Mughal emperors as a symbol of their divine right to rule and as a testament to the empire’s grandeur. The Kohinoor’s journey from the Lodhi dynasty to the Mughal Empire marked a significant chapter in its storied history, shaping its role as a symbol of power and prestige in the Indian subcontinent.

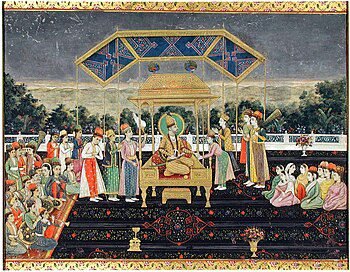

The Koh-i-noor entered its next chapter when Shah Jahan, the fifth Mughal emperor commissioned the Peacock throne to be built. Shah Jahan is renowned for his grand architectural and artistic endeavors. The Peacock Throne was designed to evoke awe and splendor. It featured a raised platform adorned with intricate gold and silver filigree, studded with a dazzling array of precious gemstones, including diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires.

The throne’s backrest was crafted in the shape of a magnificent peacock with its tail unfurled, hence its name. Skilled artisans from across the Mughal Empire were summoned to work on the Peacock Throne, employing techniques passed down through generations. But it was the Koh-i-noor that actually raised the value of the Throne to surmount all other Royal items showcasing wealth.

Then during the next emperor, Aurangzeb’s reign, the Koh-i-Noor diamond underwent alterations allegedly by the hands of Hortense Borgia, a Venetian lapidarist. Borgia, tasked with enhancing the gem’s brilliance, carelessly reduced its weight, incurring Aurangzeb’s wrath. The Emperor, angered by Borgia’s negligence, nearly sentenced him to death. However later, Aurangzeb spared Borgia’s life but imposed a heavy fine of 10,000 rupees as punishment for his error. This incident underscores the immense value placed on the Koh-i-Noor and the meticulous care required in handling such precious treasures during the Mughal era.

As the Mughal empire entered a phase of decline, it was Nader Shah whose invasion would change the journey of the Koh-i-noor diamond. Nadir Shah’s acquisition of the Kohinoor diamond is steeped in the turbulence of his conquests. In 1739, Nadir Shah, the Persian ruler, launched a devastating invasion of India, culminating in the sack of Delhi. His forces plundered the city, resulting in widespread massacre and looting. The invasion also epitomized the weakening of centralized authority in the Indian subcontinent.

During his invasion of India, he seized the Peacock Throne from the Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah. The Kohinoor, adorning the throne, captivated Nadir Shah’s attention. Its legendary beauty and historical significance were irresistible. Thus, it became part of his plunder, adding to the immense wealth looted from Delhi. The diamond’s journey from the Mughal treasury to Nadir Shah’s possession marked another chapter in its tumultuous history, further enhancing its reputation as one of the world’s most coveted gems.

Following the assassination of Nadir Shah in 1747, his vast empire plunged into chaos, leading to its eventual collapse. Amidst the power vacuum, the fate of the Koh-i-Noor diamond, once part of Nadir Shah’s treasury, shifted hands. Nadir Shah’s grandson found himself in possession of the Koh-i-Noor amidst the turmoil. Recognizing the strategic value of alliances in the volatile political landscape of the region, Ahmad Shah sought support for his burgeoning ambitions.

In 1751, Ahmad Shah Durrani, the founder of the Afghan Empire, emerged as a key player. In exchange for his military backing, Nadir Shah’s grandson bestowed the Koh-i-Noor upon Ahmad Shah, solidifying their alliance. This exchange of the Koh-i-Noor diamond for military support marked a significant chapter in its storied history. It symbolized not only the shifting alliances and power dynamics of the region but also the enduring allure and value placed upon the legendary gemstone by rulers seeking to bolster their authority.

According to British records, on one of his diplomatic visits to Afghanistan, Mounstuart Elhinstone witnessed the Koh-i-noor for the first time when it was displayed by the grandson of Ahmed Shah Durrani, Shuja Shah. He wouldn’t have known it at that point of time but it would soon be the British who would possess this legendary diamond. In 1809, Shah Shuja sought assistance from the United Kingdom amid rising concerns over a potential Russian invasion. Forming an alliance, Shah Shuja hoped to bolster his defenses against advancing Russian threats. However, his plans were swiftly thwarted as internal unrest led to his overthrow from power.

Despite being deposed, Shah Shuja managed to escape with the Koh-i-Noor diamond in his possession. Fleeing to Lahore, which was part of the Sikh Empire under the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Shah Shuja sought refuge and sanctuary. n a gesture of hospitality, Maharaja Ranjit Singh extended his protection to Shah Shuja. However, in return for his generosity, Singh insisted that the Koh-i-Noor diamond be relinquished to him. In 1813, Shah Shuja, recognizing the precariousness of his situation and indebted to Ranjit Singh for his hospitality, acceded to Singh’s request. The Koh-i-Noor diamond thus passed into the possession of Ranjit Singh, becoming part of the vast treasures of the Sikh Empire.

This instance highlights the complex interplay of diplomacy, power dynamics, and personal ambitions in the geopolitics of the time. The Koh-i-Noor diamond, a symbol of wealth and prestige, was coveted by rulers seeking to assert their authority and strengthen their positions amidst the ever-shifting alliances and conflicts of the early 19th century.

Upon acquiring the Koh-i-Noor diamond from Shah Shuja in 1813, Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Sikh Empire proudly displayed the gem as a symbol of his authority and opulence. Singh, known for his grandeur and strategic flair, affixed the diamond to the front of his turban, ensuring that it became a prominent feature of his attire. During ceremonial occasions and major festivals like Diwali and Dussehra, Singh adorned himself with the Koh-i-Noor, wearing it as an armlet to dazzle his subjects with its brilliance. His elephant-mounted processions provided opportunities for his people to catch a glimpse of the renowned gem, further cementing his status as a powerful and prestigious ruler.

Additionally, Singh recognized the diplomatic value of the Koh-i-Noor and strategically exhibited it to important visitors, particularly British officers. By showcasing the diamond to such prominent figures, Singh aimed to assert his authority and cultivate favorable relations with the British, while also emphasizing the wealth and splendor of his empire.

However with Ranjit Singh’s death, his empire entered a period of decline. After a period of chaos, his 5 year old son, Duleep Singh became the Maharaja. Soon the Second Anglo-Sikh war resulted in the Sikh Empire’s defeat and subsequent acquisition of the Kohinoor diamond by the British. Article 3 of the Treaty of Lahore reads –

“The gem called the Koh-i-Noor, which was taken from Shah Sooja-ool-moolk by Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, shall be surrendered by the Maharajah of Lahore to the Queen of England.”

The Koh-i-Noor diamond, steeped in history and legend, was finally ceremoniously bestowed upon Queen Victoria on 3rd July 1850 at Buckingham Palace. Presented by the deputy chairman of the East India Company, this event coincided with the Company’s 250th anniversary, marking a symbolic fusion of imperial power and colonial acquisition, further solidifying the diamond’s place in the annals of British royal treasures.

Till date, the ownership of the Kohinoor diamond remains a subject of contentious debate, steeped in historical grievances and cultural significance. India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and even Iran have all staked claims to the legendary gem, each citing historical, legal, and cultural arguments to support their ownership rights. Conversely, the British government maintains its ownership of the Kohinoor, rejecting calls for its return and citing legal agreements and historical contexts as justification. The diamond remains prominently displayed in the Crown Jewels collection at the Tower of London, serving as a tangible reminder of Britain’s colonial past and imperial legacy.

Amidst the controversy, calls for a diplomatic resolution or shared ownership arrangement have also surfaced, acknowledging the complex historical and cultural significance of the Kohinoor to multiple nations. The dispute over the ownership of the Kohinoor diamond underscores larger issues of colonial restitution, cultural heritage preservation, and national identity, highlighting the enduring impact of colonialism on global relations and the complexities of historical grievances in the modern era.

Amidst the controversy, calls for a diplomatic resolution or shared ownership arrangement have also surfaced, acknowledging the complex historical and cultural significance of the Kohinoor to multiple nations. The dispute over the ownership of the Kohinoor diamond underscores larger issues of colonial restitution, cultural heritage preservation, and national identity, highlighting the enduring impact of colonialism on global relations and the complexities of historical grievances in the modern era.