Lost Artifacts: Indus Valley Civilisations – Script and Seals

In the 1850s, Chales Masson, a soldier of the East Indian Company was exploring the dusty plains of Punjab when he came across the apparent ruins of an abandoned and forgotten town. It was not until 1920 that the Indian archaeologist, Daya Ram Sahni started excavations and conducted a path-breaking archaeological discovery which finally revealed the antiquity of Indian Civilisation.

The Indus Valley Civilization, which spanned from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE, holds pivotal significance in not just Indian, but also human history. The advanced urban planning, sophisticated engineering, and thriving trade networks reveal the advanced nature of early Indian societal organization and its technological prowess. With standardized weights, writing systems, and cultural icons, it showcases the early administrative structures and cultural richness. The Harappan Civilisation influenced later societies and greatly contributed to the cultural tapestry of South Asia.

Yet there is one major problem that has stopped historians from completely understanding the nuances of this civilisation and has kept the civilisation still shrouded in secrecy and mystery. This problem is the great difficulty in deciphering the script of the Harappan civilisation. There are many reasons for this challenging endeavor.

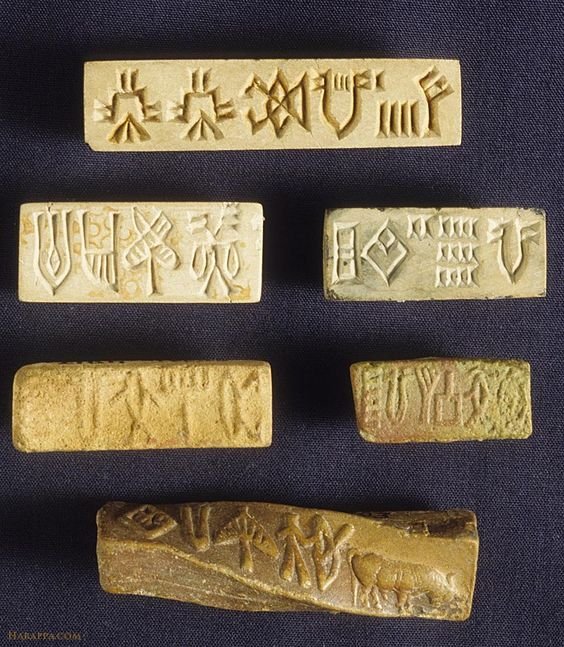

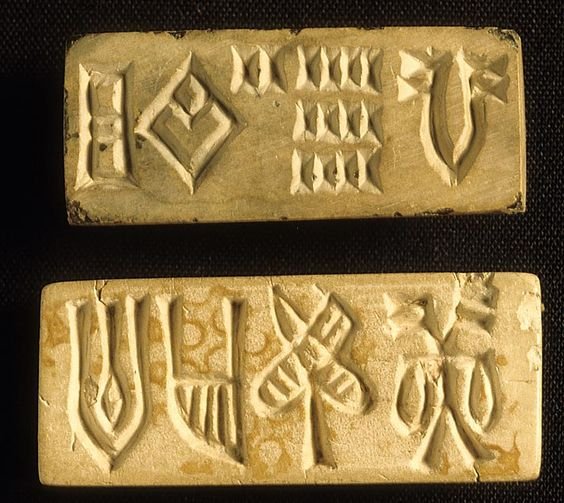

Deciphering the enigmatic script of the Indus Valley Civilization is a complex puzzle fraught with numerous challenges. One of the primary hurdles lies in the extreme brevity of the Indus texts. On an average, these inscriptions comprise only about five signs, with even the longest texts consisting of merely fourteen signs in a single line. Such brevity severely limits the amount of information available for analysis, making it difficult to discern patterns or establish meaningful linguistic relationships.

Adding to the difficulty is the absence of contextual information surrounding the usage of these texts. Unlike other ancient scripts that may be accompanied by explanatory texts or inscriptions in different languages, the Indus script lacks such contextual clues. Without a clear understanding of the social, religious, or administrative contexts in which these inscriptions were employed, decipherment efforts face significant limitations.

Moreover, the absence of bilingual or multilingual texts poses a significant challenge. Bilingual inscriptions, as seen in the Rosetta Stone, provide invaluable comparative data that aids in decipherment. However, such complementary texts are conspicuously absent in the case of the Indus script, leaving scholars without a linguistic Rosetta Stone to guide their efforts.

Another critical obstacle is the lack of knowledge about the language or possibly, languages spoken by the inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilization. Unlike deciphered ancient scripts such as cuneiform or hieroglyphs, the linguistic framework underlying the Indus script remains elusive. Without a firm grasp of the underlying language, decipherment efforts are akin to attempting to solve a puzzle without knowing the correct pieces.

Also, the cultural traditions of the Civilisation are not uninterrupted. This further muddles the decipherment efforts. The absence of direct linguistic descendants or clear continuity in cultural practices makes it challenging to trace the evolution of language or decipherment clues beyond the civilization’s demise.

Despite these formidable challenges, scholars continue to employ interdisciplinary approaches and innovative methodologies in their quest to unlock the secrets of the Indus script. The mystery surrounding the script has led to various theories and hypotheses, but none have yielded definitive results. Some scholars argue that it represents a logo-syllabic script, while others propose a proto-Dravidian or proto-Elamite origin. Advances in computational linguistics, statistical analysis, and archaeological discoveries offer hope for eventual breakthroughs in decipherment. However, until these hurdles are overcome, the script of the Indus Valley Civilization remains one of the most enduring mysteries of ancient history, tantalizing researchers with its elusive secrets.

The inability to understand the script hampers our ability to reconstruct the Indus Valley Civilization’s history, societal structure, and cultural practices. It impedes our understanding of trade networks, diplomatic relations, and interactions with contemporary civilizations. Resolving this linguistic puzzle is crucial for unlocking the full extent of the civilization’s contributions to human history and civilization. Apart from this enigmatic script that has so far succeeded in keeping the history of this civilisation so mysterious, the Harappan seals speak a language of their own.

In the Indus Valley civilisation, stone seals were carefully constructed and fired to ensure their durability. These seals had a variety of purposes inside the ancient culture. These seals were primarily used for trading, but they were also used for sealing jars and labeling bags, which helped the civilization’s expanding economy. Remarkably, a sizable concentration of these seals was discovered in the port city of Lothal in the Indus Valley, highlighting its significance as a center for maritime trade and commerce.

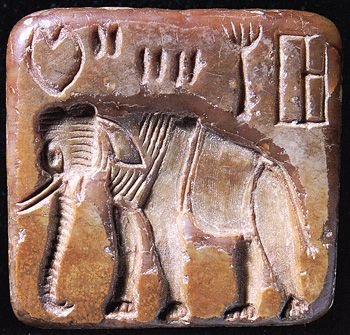

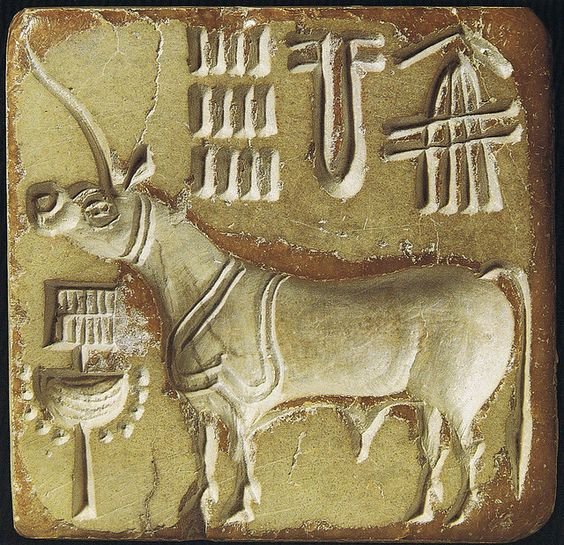

The finding of Harappan seals in far-off places like Mesopotamia and Central Asia offers strong proof of vast trade networks and cross-cultural interactions between ancient civilizations. The Indus Valley civilization’s inventiveness and creative diversity are reflected in these seals, which are distinguished by their many shapes. But in Harappan society, square-shaped seals became the most common type.

Harappan seals were made mostly of steatite, a soft stone that is easily found in river bottoms. However, they were also made of copper, terracotta, chert, faience, agate, gold, and ivory, demonstrating the civilization’s skill in using a range of materials. It’s interesting to note that certain seals were found buried with the dead, indicating that they may have had ceremonial or symbolic meaning—perhaps as necklace ornaments or protective amulets.

The seals themselves had complex pictographic scripts or symbols on one side that were typically written in a bidirectional or right-to-left manner, suggesting a highly developed communication system. The other side included finely carved animal impressions that showed a wide variety of animals, such as tigers, buffalos, elephants, and more. The quintessential Harappan seal was square in shape, with symbols on top, an animal motif in the middle, and more symbols at the bottom, representing the essence of Harappan symbolism and craftsmanship.

One particular seal that has created much discussion regarding its true meaning and interpretation is the “Pashupati seal”. Among the several seals found from the Indus Valley civilization, this one stands out for its elaborate design, which centers on a human figure instead of animals found on such seals. According to some historians, it might be a representation of a proto-Shiva figure. Yet this interpretation is hotly debated.

Primary amongst those championing the seal representing a Proto-Shiva was John Marshall, one of the earliest archaeologists who worked on excavating the Harappan civilisation. He stated his arguments as follows – “My reasons for the identification are four. In the first place the figure has three faces and that Siva was portrayed with three as well as with more usual five faces, there are abundant examples to prove. Secondly, the head is crowned with the horns of a bull and the trisula are characteristic emblems of Siva. Thirdly, the figure is in a typical yoga attitude, and Siva [sic] was and still is, regarded as a mahayogi—the prince of Yogis. Fourthly, he is surrounded by animals, and Siva is par excellence the “Lord of Animals” (Pasupati)—of the wild animals of the jungle, according to the Vedic meaning of the word pashu, no less than that of domesticated cattle.”

Academics like Doris Srinivasan and Alf Hiltebeitel have considered the figure as a representation of prototypes of Non-Vedic Gods. Other historians have been more cautious in making interpretations. Wendy Doniger believes that “we cannot know it, [and] it does not mean that the Indus images are the source of the Hindu images, or that they had the same meaning.”

Today, archaeological findings have reached an exciting phase where every few months, a new site is being discovered because of the breathtaking speed at which science is progressing. Currently, the ASI is focused on excavations around Rakhigarhi. Situated in present-day Haryana, India, Rakhigarhi represents one of the largest and Harappan settlements discovered to date. There is also much excitement regarding the fact that much of it remains to be excavated yet and the emerging evidence that Rakhigarhi may actually predate the Harappan civilisation.

One of the most significant discoveries at Rakhigarhi is its cemetery, which provides invaluable insights into Harappan burial practices and mortuary rituals. Archaeologists have uncovered multiple burial pits containing skeletal remains, pottery, ornaments, and other grave goods. Analysis of these burials has shed light on aspects such as social status, health, and diet of the ancient inhabitants. Furthermore, the presence of elaborate grave goods suggests a belief in an afterlife or reverence for ancestors, underscoring the spiritual and cultural dimensions of Harappan society.

In recent years, Rakhigarhi has attracted significant attention from archaeologists, historians, and the public alike. Ongoing excavations, scientific analyses, and interdisciplinary research continue to deepen our understanding of the Indus Valley Civilization and its significance in world history. Furthermore, efforts in heritage conservation and site management aim to preserve Rakhigarhi’s cultural legacy for future generations and promote awareness of its importance in shaping the history and identity of South Asia.

Advancements in technology have revolutionized archaeological research in the Indus Valley region. Ground-penetrating radar (GPR), LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), and other remote sensing techniques have enabled archaeologists to survey large areas efficiently and non-invasively, identifying buried structures and subsurface features with unprecedented accuracy. These technologies have facilitated the discovery of previously unknown sites and enhanced our understanding of urban planning, settlement patterns, and environmental adaptations of the Harappan civilization.

Furthermore, interdisciplinary approaches combining archaeology with scientific analyses have yielded valuable insights into various aspects of Harappan life. Isotopic analysis of human skeletal remains has provided information about diet, migration patterns, and social interactions. DNA analysis has offered insights into population genetics and genetic affinities with present-day populations. Studies of ancient plant remains and animal bones have revealed agricultural practices, domestication processes, and subsistence strategies of the Harappan people.

In addition to on-site excavations, ongoing efforts in heritage conservation, site management, and public outreach play a crucial role in preserving and promoting awareness of the Indus Valley Civilization’s rich cultural heritage. Museums, interpretive centers, and educational programs contribute to disseminating knowledge about the significance of the Harappan civilization and its enduring legacy in shaping South Asian history and culture.

In conclusion, the ongoing excavations in the Indus Valley Civilization represent a relentless pursuit to uncover the intricacies of one of the ancient world’s most enigmatic civilizations. Through a combination of meticulous fieldwork, technological advancements, and interdisciplinary collaborations, archaeologists are gradually unraveling the complexities of Harappan society. Moreover, scientific analyses of artifacts, skeletal remains, and ancient DNA offer opportunities to explore questions of migration, population dynamics, and genetic affinities. Through these multidisciplinary approaches, researchers aim to construct a comprehensive understanding of the Harappan world, connecting the dots between archaeological evidence and broader historical narratives.

Each discovery adds another piece to the puzzle, offering glimpses into the daily lives, religious beliefs, social structures, and remarkable achievements of the people who inhabited the fertile plains of the Indus River valley millennia ago.

As excavations continue and new technologies emerge, the study of the Indus Valley Civilization remains dynamic and ever-evolving. Each revelation deepens our appreciation for the ingenuity and resilience of these ancient peoples, while also challenging us to rethink our assumptions about the past. Ultimately, the exploration of the Indus Valley Civilization is not just a journey into history but a quest to understand the complexities of human civilization and our shared human heritage.