Decoding Bharavi’s Literary Heritage: Unveiling the Epic Odyssey of an Ancient Poet

- Ancient history Asian history

Nida Farooqui

Nida Farooqui- December 7, 2023

- 0

- 283

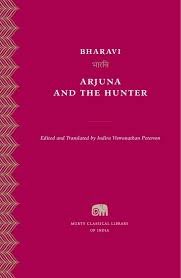

Bharavi, who thrived in the 6th century AD, was a Sanskrit poet renowned for creating the epic “Kiratarjuniya” (”Arjuna and the Mountain Man”). This classical Sanskrit epic falls under the category of mahakavya, or “great poem.” Marked by its elevated expression and intricate style, Bharavi’s poetry possibly left an imprint on the work of the 8th-century poet Magha. The mention of Bharavi’s name, coupled with the renowned Sanskrit poet and dramatist Kālidāsa, appears in a Chalukya stone inscription dating back to 634 C.E., discovered at Aihole in present-day Karnataka. Additionally, an inscription by King Durvinita of the Western Ganga Dynasty reveals that he authored a commentary on the fifteenth canto of Bharavi’s epic, Kiratarjuniya.

Kiratarjuniya, Bharavi’s Epic

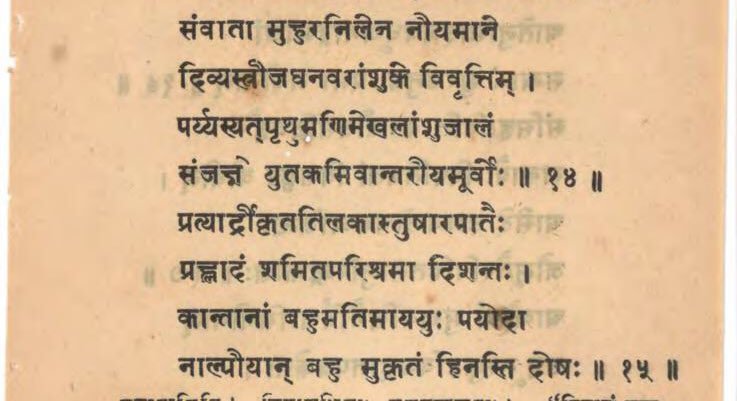

Bharavi’s sole known composition is the eighteen-canto epic poem, Kirātārjunīya, drawing its narrative from the Mahābhārata. Widely acclaimed as the most powerful poem in Sanskrit, A. K. Warder goes so far as to deem it the “most flawless epic available to us,” surpassing even Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacharita. Warder commends Bharavi for his heightened force of expression, meticulous attention to detail, and a more concentrated and polished form. Despite employing a highly challenging language and delving into the intricacies of Sanskrit grammar, Bharavi achieves a remarkable conciseness and directness. His adept use of alliteration, the “crisp texture of sound,” and his selection of metre seamlessly align with the unfolding narrative.

Bharavi’s poetry is distinguished by its intricate styles and transcendent expressions. Much like Kalidasa is celebrated for his similes (upamā) and Daṇḍin for his wordplay (padalālityam), Bharavi is renowned for the profound depth of meaning (artha gauravam) embedded in his work. It is believed that Bharavi’s Kiratarjuniya exerted a significant influence on the 8th-century CE poet Magha’s Shishupala Vadha.

Thought to be composed in the 6th century or earlier, Kirātārjunīya comprises eighteen cantos recounting the fierce battle between Arjuna and Shiva, who assumes the guise of a kirata, or “mountain-dwelling hunter.” Ranked among the trio of larger Sanskrit mahakavyas, including the Naiṣadhacarita and the Shishupala Vadha, it stands as one of the six great epics of Sanskrit literature. This work is distinguished by Sanskrit critics not only for its profound depth of meaning but also for its compelling and occasionally playful expression. Notably, a canto is dedicated to showcasing linguistic prowess, akin to constrained writing. Subsequent epic poems drew inspiration from the Kirātārjunīya’s model.

In the Kirātārjunīya, the predominant emotion is the Vīra rasa, or the mood of valour. The epic elaborates on a minor episode found in the Vana Parva (“Book of the Forest”) of the Mahabharata: During the Pandavas’ exile in the forest, Draupadi and Bhima persuade Yudhishthira to wage war against the Kauravas, a proposal he initially resists. Ultimately, Arjuna, guided by Indra’s counsel, undergoes penance (tapasya) in the forest to appease Shiva. Impressed by Arjuna’s austerities, Shiva decides to reward him.

A demon named Muka, assuming the form of a wild boar, charges at Arjuna. In response, Shiva manifests as a kirata, a wild mountaineer. Arjuna and the kirata simultaneously release arrows at the boar, successfully killing it. An argument ensues over who shot first, leading to a protracted battle between Arjuna and the kirata. Despite Arjuna’s valiant efforts, he is astonished to find himself unable to defeat this mysterious mountain-dweller. Eventually, Arjuna realises the divine identity of his opponent and surrenders. Pleased with Arjuna’s courage, Shiva rewards him with the formidable weapon, the Pashupatastra. It’s noteworthy that within the Mahabharata, only Arjuna possesses the Pashupatastra.

Reception of his work

The Kirātārjunīya garnered acclaim from critics, inspiring over 42 commentaries. Bharavi’s distinctive style, particularly evident in cantos 4 to 9, where the focus shifts from the plot to exquisite descriptive poetry, left a lasting impact on subsequent Sanskrit epic poetry. This departure from emphasising action influenced a significant shift in the genre. More than a tenth of the verses from the Kirātārjunīya find their way into anthologies and works on poetics. The 37th verse from the eighth canto, depicting nymphs bathing in a river, stands out for its beauty and remains a favourite. Another verse from the fifth canto, renowned for its imagery, earned Bharavi the moniker “Chhatra Bharavi” as it vividly portrays lotus flower pollen blown by the wind into a golden umbrella (Chhatra) in the sky. The work is celebrated for its harmonious blend of verses appealing to laypeople and intellectually engaging verses appreciated by scholars. This quality, described as samastalokarañjakatva, contributes to the Kirātārjunīya’s reputation for delighting audiences at all levels.

As the sole known work of Bharavi, the Kirātārjunīya holds a unique position and is hailed as “the most powerful poem in the Sanskrit language.” A. K. Warder goes a step further, declaring it the “most perfect epic available to us,” surpassing Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita. This distinction is attributed to Bharavi’s exceptional force of expression, meticulous concentration, and polished detail. Despite employing a highly complex language and revelling in the nuances of Sanskrit grammar, Bharavi achieves clarity and directness. His use of alliteration, a “crisp texture of sound,” and the choice of metre harmoniously align with the narrative, contributing to the epic’s enduring appeal.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Bharavi’s Kirātārjunīya stands as a monumental achievement in Sanskrit literature, earning its place as “the most powerful poem in the Sanskrit language.” This singular work, the only known creation of Bharavi, has left an indelible mark on the literary landscape, influencing subsequent epic poetry with its unique blend of descriptive beauty and intellectual engagement. With more than 42 commentaries attesting to its enduring appeal, the Kirātārjunīya is celebrated for its harmonious balance, captivating both lay audiences and scholars alike. Bharavi’s distinctive style, characterised by exquisite poetry and a departure from plot-centric narratives, has set a precedent for the genre. The work’s verses, including the renowned depictions of nymphs and evocative imagery, continue to resonate and find their place in anthologies and discussions on poetics.

K. Warder’s acclaim of the Kirātārjunīya as the “most perfect epic available to us” underscores its literary prowess, surpassing even celebrated works like Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita. Bharavi’s ability to navigate complex language and intricate Sanskrit grammar while maintaining clarity and directness is a testament to his skill as a poet. The enduring influence of this epic, from its powerful expressions to its meticulous details, cements Bharavi’s legacy as a literary luminary. In exploring the Kirātārjunīya, we not only unravel the narrative intricacies of an ancient poet but also witness the timeless allure of a work that continues to captivate and inspire generations.