LASCAUX CAVES: A Gateway to the Palaeolithic Murals

Amidst all the historical archaeological evidences comprising monuments, sculptures, inscriptions, coins, pillars, literature, manuscripts etc, Cave art and paintings outshine the most while revealing the unravelled forlorn stories and instances which are ages old, yet are lively of eternal ritual of art. One among many such historical caves, is the strikingly breathtaking Lascaux Caves, also known as Lascaux Grotto and Grotte de Lascaux in French serving as a shelter to the most intricately idyllic and vivid portrayals of prehistoric artwork belonging to the Palaeolithic age dating back to 17000-15000 BCE.

Nestled in southwestern France, near the village of Montignac in the Dordogne region, embracing Vézère Valley which is a home to numerous such caves discovered since the beginning of the 20th century (for example Les Combarelles and Font-de-Gaume in 1901, Bernifal in 1902), and embodying countless prehistoric paintings, Lascaux Grotto contains nearly 1,500 engravings, and around 600 simulacrums of animals, such as deer, bison, and even some felines. Lascaux Grotto is located just a short distance upstream from the Eyzies-de-Tayac cave system.

It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979. Regarding Lascaux Grotto, UNESCO notes: “The hunting scenes show some 100 animal figures, which are remarkable for their detail, rich colours and lifelike quality.”

Accidental Discovery and Excavation

Unknown to the extraordinary discovery they would make for the archaeologists of the world, in September 1940, four boys in desperate search of their lost dog, accidentally came across a foxhole down which their dog had fallen on the hill of Lascaux. After exploring further and expanding the entrance, Marcel Ravidat was the first to descend to the bottom, followed by his three friends. They constructed a makeshift lamp to illuminate their path and discovered a greater variety of animal wall paintings and depictions in the Axial Gallery than they had anticipated. The next day, they returned better prepared and ventured deeper into the cave. Astounded by their discovery, the boys informed their teacher, initiating the process of excavating the cave a week after by archaeologists and historians to examine and authenticate the figures. It was opened for the public and tourists 1948 onwards.

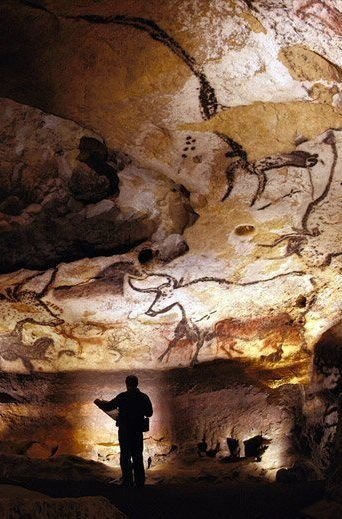

The cave is approximately 20 metres wide with a height of 5 metres. The cave was in an undisturbed condition, hermetically packed and unaffected by sudden temperature changes. Moreover, a layer of clay in the soil made it watertight and dry, which can be ascertained as the major reason for the survival of these antique paintings. The cave has several deep passages and rooms or halls. It has been demarcated into seven sectors namely, the Great Hall of the Bulls, the Lateral Passage, the Shaft of the Dead Man, the Chamber of Engravings, the Painted Gallery, the Nave, and the Chamber of Felines.

THE ANTIQUE ART

Adorned with ‘parietal art’ which refers to the paintings and engravings found on the walls of caves, Lascaux is sketched with most representations of animals native to the region, some abstract symbols (such as dots, lines, and geometric shapes) and a bird-headed figure which is designated to be the only human figure in the cave as humans are rare in Palaeolithic art.

Experts have pinpointed more than 900 images as animal depictions, with 605 of these being precisely identified. Among these animal images, there are 364 paintings of horses and 90 of stags. Cattle and bison make up 4 to 5 percent of the images which render one of the initial sections of the cave as ‘The Hall of the Bulls’. Additionally, the cave features images of other animals, such as felines, birds, a bear, and a rhinoceros. The illustrations were both painted and engraved into the walls.

The Great Hall Of The Bulls

Also known as Rotunda, the Hall of the Bulls, about 65.6 feet (20 metres) long, and width varying between 18 and 24.6 feet (5.5 and 7.5 metres) is the most outstanding main chamber of art which is aptly named as it largely displays aurochs, an extinct cattle. Four bulls are depicted in a roundabout of dance towering above fleeing horses. The humans of that time were savvy artists, possessing great skill shown by the sketching of animals in side view with their horns turned reflecting a realistic picturesque. One of the bulls is 17 feet (5.2 metres) long and is the largest animal discovered so far in cave art. While most figures are identifiable, some are indecipherable, for instance, the seemingly pregnant horse with a horn-like structure on its head and a peculiar figure depicted with panther skin, a deer’s tail, a bison’s hump, two horns, and a male member. Some have suggested it to be wizard or sorcerer but it’s difficult to claim so.

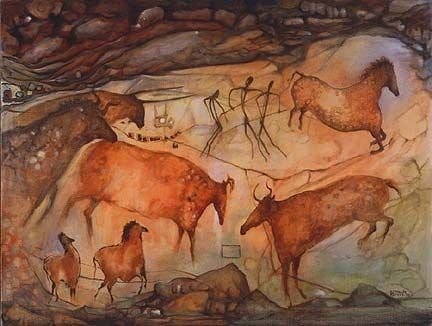

Axial Gallery

Revered as ‘Sistine Chapel of Prehistory,’ Axial Gallery which lies beyond the Hall of the Bulls has a ceiling festooned with awe-inspiring compositions. Red aurochs are depicted with their heads forming a circle. The main figures in the Gallery stand facing each other: a powerful black bull on one side, and a female aurochs on the other, appearing to leap onto a lattice drawn beneath her hooves. There are numerous horse depictions, including one called the ‘Chinese horse,’ with its hooves shown slightly behind, showcasing an advanced use of perspective. Towards the back of the passage, a horse is illustrated galloping with its mane flowing, while its companion is shown falling with its legs in the air.

Unfathomable depictions in other chambers

A passage from the second exit from the Hall of Bulls, largely containing engravings, leads to the Nave, where a large black bull and two bison standout due to their wild energy, appearing to retreat. Opposite them, a frieze depicts five deer that seem to be swimming. After the Nave, the Chamber of Felines introduces predators, with engravings of tyranny of lions captivating the scene. In another part of the cave, the Shaft of the Dead Man offers more intriguing material wherein besides a wounded bison with its intestines spilling out, there are depictions of a woolly rhinoceros, a bird on what appears to be a stick, and a naked man with an erect member. This imagery definitely conveys a story, though its precise meaning and sense remains uncertain.

The Tools and Techniques deployed

The prehistoric homo sapiens prudently chose the technique and tools to draw the compositions which varied according to the characteristics of the base used (the walls and ceiling of the cave) which is suggestive of the fact that they were much ahead of their time. For instance, in the Hall of the Bulls, the support is rough and hard making drawing the best alternative whereas in the Chamber of the Felines, figures were created by engraving, as the rock had begun to disintegrate slightly due to corrosion. Another technique involved painting by blowing dried paint through tools made from hollow bones.

The artists made the most of the environment of the cave by using the natural shapes of the rocks as parts of the figures. Similarly, in this manner, the shape of the wall partially assisted in the construction of animal silhouettes. Scaffolding might also have been used in the process of painting as some compositions are located significantly high beyond 2.5 metres, where the walls meet the ceiling.

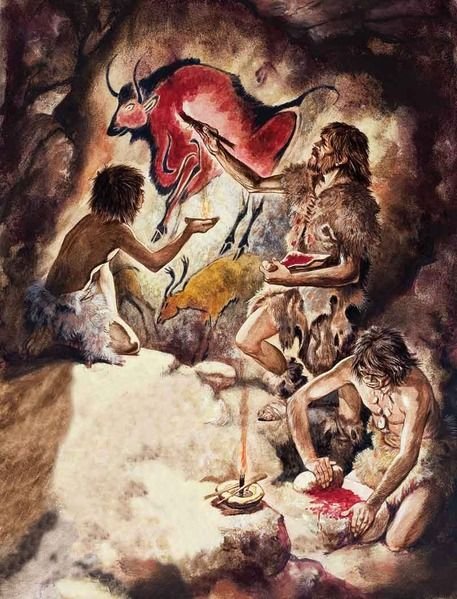

From the artefacts found in the cave, we know that the deeper sections were illuminated by sandstone lamps fueled by animal fat and by fireplaces. The artists worked in what must have been smoky conditions, using minerals as pigments for their creations and colours. Majorly black, brown, red and yellow colours were used. Other colours, such as mauve, appear but are quite rare. In parietal cave art, talc was sometimes added to rare pigments to enhance their application.

Red pigments were made from hematite, either in its raw form or within red clay and ochre; yellow from iron oxyhydroxides; and black from either charcoal or manganese oxides. The pigments were prepared by grinding, mixing, or heating, and then applied to the cave walls. Painting techniques included drawing with fingers or charcoal, applying pigment with brushes made of hair or moss, and blowing the pigment onto a stencil or directly onto the wall using tools like hollow bones.

One notably engrossing fact is that there are no specific manganese oxides deposits found anywhere near Lascaux and the closest known source is located some 250 kilometres away, in the central Pyrenees, which serves as an indication to a trade or supply route. But it was common for humans of that period to source their material resources from far away places which further pinpoints to the zeal of efforts the Lascaux artists put in.

In addition to the artwork at Lascaux, a variety of implements were uncovered. Numerous flint instruments showed evidence of being employed to etch marks on the cave walls. There were also instruments made from bones. The colouring materials found at the site had reindeer antler particles in them, possibly from carving the antlers near the colourants or using them as a mixing agent with water. Furthermore, shell remnants, some fashioned with holes, were discovered and aligned with additional finds suggesting that personal ornaments were utilised by Upper Paleolithic Europeans.

WHY WERE THESE PAINTINGS CREATED?

Though the cave art is admirable, it is as enigmatic and cryptic as archeologists have not been able to unearth the meaning and story behind the creation of these art pieces. The cave was difficult to access, with some deepest and darkest chambers being especially inaccessible, indicating it was not used as a habitation. Therefore, there is uncertainty about the intention of the Paleolithic humans behind stroking these depictions on cave walls.

For a while, the “art for art’s sake” theory (pure artistic expression) was considered, but it lacks substantial support. One of the main theories is that the paintings had a ritual significance, possibly related to “hunting magic.” It is also suggested that the images might carry narratives and stories.

THE LASCAUX REPLICA

The cave was made inaccessible to the public in 1963 after it suffered from damage like fading of the colours of the paintings, growth of algae, and exposure to outside temperature conditions which have significantly affected the cave. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the Lascaux caves have been afflicted by a fungal outbreak. The issue has been attributed to several potential factors, including the installation of a new air conditioning system, the usage of intense lighting, and excessive visitor traffic. By 2006, the situation had worsened with the emergence of black mould. Consequently, in January 2008, the caves were temporarily sealed off from everyone, including scientists and conservators, for a period of three months. During this time, only one person was permitted to enter the cave for a brief 20-minute session weekly to check the environmental conditions.

As it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979 along with other 25 painted caves and 147 prehistoric settlements located in the Vézère valley, numerous conservation and preservation efforts have been made and are ongoing to shield and sustain the artwork. Moreover, three replicas have been created for visitors to witness the remnants of a bygone age. The first replica, known as Lascaux II, is situated less than 200 metres from the original cave and replicates the Great Hall of the Bulls and the Painted Gallery sections. There is also Lascaux III, a mobile exhibition, and Lascaux IV, the most recent and complete replica. Owing to 3D digital scanning, every centimetre of the original cave has been recreated using polystyrene, resin, and fibreglass techniques. A team of 34 artists meticulously copied the paintings onto the new walls and ceilings. Additionally, a virtual tour of the cave is available. Recently in Paris, over 200 experts gathered for a symposium to address the preservation of Lascaux’s priceless treasures. Organised by France’s Ministry of Culture and Communication and led by Dr. Jean Clottes, the event aimed to find solutions for their future conservation.

Conclusively, the Lascaux Grotto stands as the most extraordinary pathway to dwell into the mysteries of a forgotten era and unravel the lesser known habits of our prehistoric ancestors.