The Mysteries Of The Alluring Grand Peacock Throne

The Mughal Empire has produced unparalleled artistic pieces of art, jewellery, architecture and most of all the royal seats of their Empire’s rulers.

Studded with opulent gemstones and rare metals with intricate designs, their thrones were not just mere seats for their grand Emperors – they were symbols of power and the glory for this remarkable Empire which has been remembered in history.

We will delve into the workmanship of the legendary Peacock Throne also known as Takht-i-Khaus. From its conceptualization to its mysterious disappearance and the fabled rumours surrounding it, we will uncover the radiance of the Mughal Empire and the Central seat of the Peacock Throne in the exploration of imperial legacy.

The Founding Blocks of The Throne

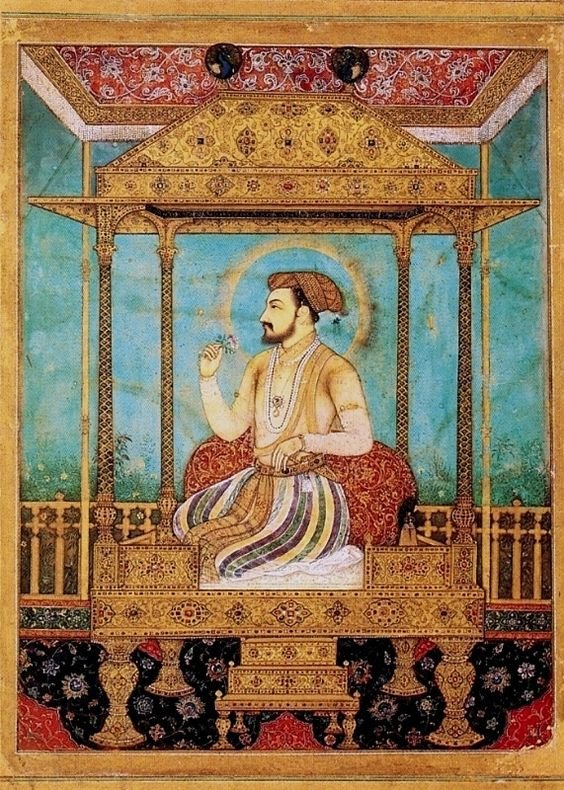

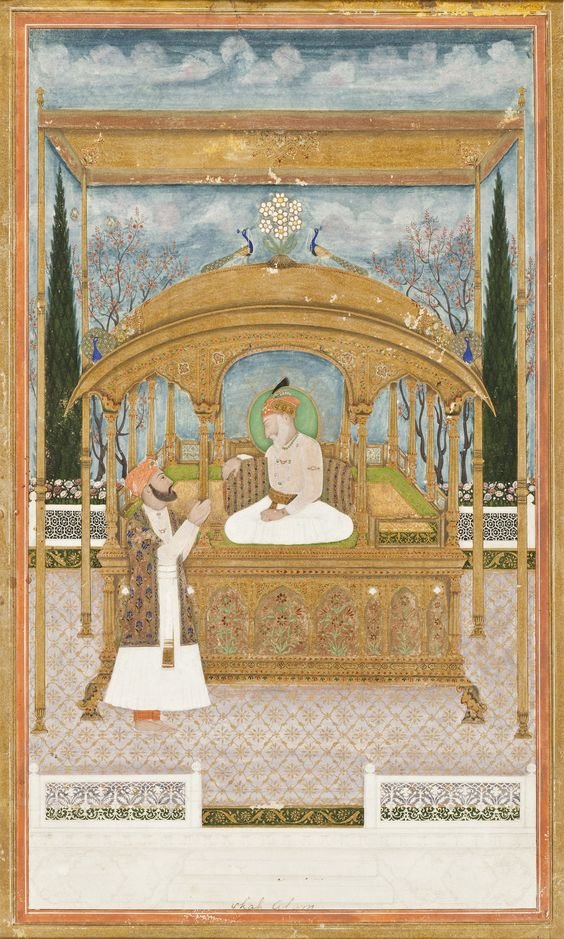

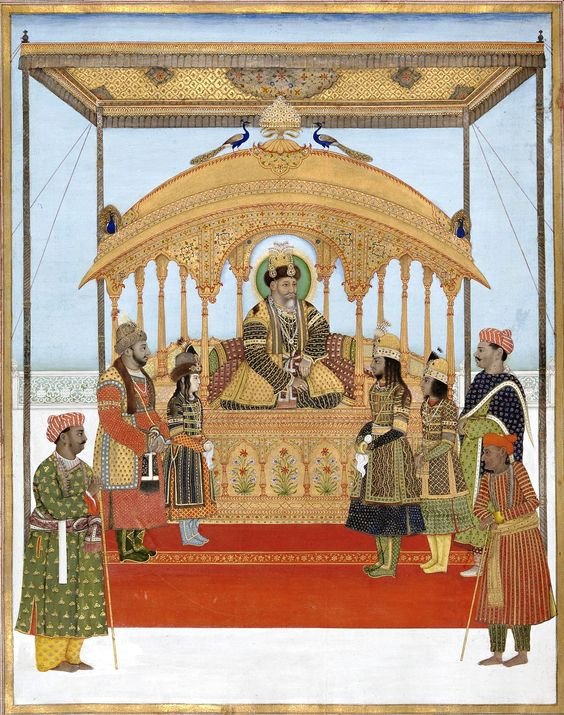

When Shah Jahan ruled, the Mughal Empire was at its peak of the Golden age. He had conquered and acquired many lands and vast areas including reestablishing the capital and the decorated Red Fort. Shah Jahan wished to be an eminent ruler and the Solomon, the “Shadow of God”, who carries out the will of God. For this to be true and symbolised, The Peacock throne was commissioned by the luminous Emperor Shah Jahan.

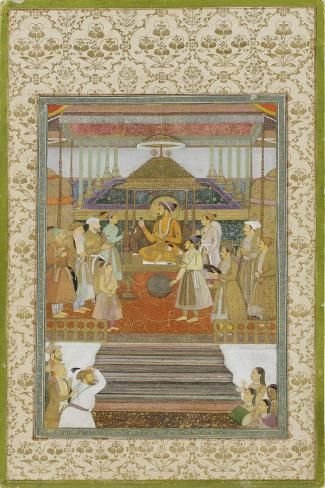

The throne was commissioned in the 17th century, started by Tamerlane but finished by Shah Jahan. Records by various researchers say that the throne took seven years to finish. It was unparalleled and grand just as a seat of the Emperor of the vast Mughal Empire should be, almost signifying a seat of a God. The Peacock throne was placed in the Diwan-e-Khas (“Hall of private audience”) which was the Emperor’s courtroom and this was situated in Delhi, which was established as the capital of the Mughal’s vast Empire.

The concept of the throne was to use the Central Asian art elements with Indian influences and Persian concepts to make a harmony of cultures and contrast with no cost to spare. Shah Jahan wanted his throne to rival the stories of the throne of Maharaja VikramAditya and surpass the level set in that age. The throne was built in such a way everyone viewing the Emperor would have a vantage view point and a majestic angle.

A majority of Royalty held gemstones, rubies and diamonds in their possession. Shah Jahan knew that India was the only country with operational Diamond mines. Hundreds of precious diamonds and gemstones were used in the making and no opportunity was lost to add in even more to the glamorous throne.The point of making the throne was to make it in such a way that it encompassed the vastness of the Emperor and the Empire. During the work, its dimensions were increased such that The Grand Throne almost rivalled the size of a small tent house.

The Ever Growing Kingdom

Shah Jahan’s empire was vast. He was the fifth Mughal Emperor and ruled for 30 years from 1628 to 1658 expanding the Empire through territorial conquests, annexations and military campaigns. Shah Jahan had added many regions into the Empire before and during the construction of the Peacock Throne. He had several conquests in the Deccan, struggling with the southern Indian powers capturing his forts as well. He regained control of the city of Kandahar in 1638 which was lost during his father’s reign. He also had several conquests there and the religion now sits in Afghanistan. He had several key forts and regions to strengthen the Empire’s defensive capabilities and power.

During his reign, Shah Jahan took interest in the culture and traditions around him. He was a very inclusive ruler and encouraged the Indian influence and the Persian elements into the constructions of palaces and tombs like the Taj Mahal. His patronage to the arts and commitment to his imperial endeavours is very apparent and visible in the structure built during his reign under his supervision and expertise.

The Design Deconstruction and Symbolism Of The Throne

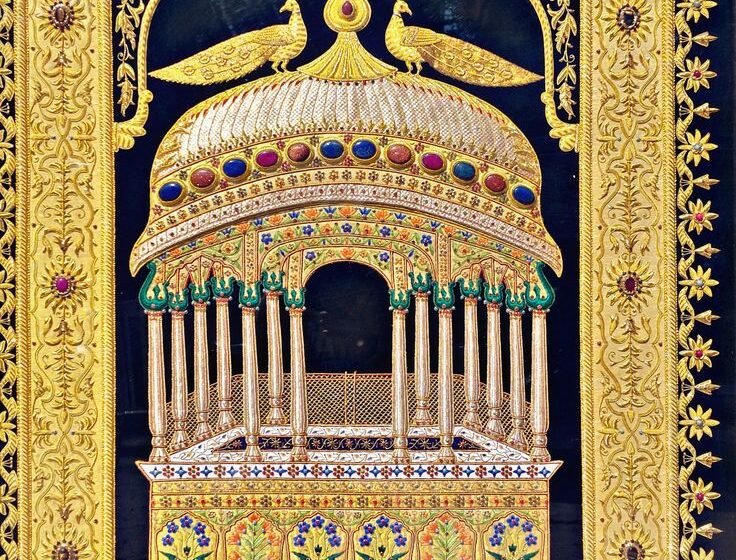

The name of throne was derived from the two grand peacocks flaring their tail feathers out in full which was studded with multi coloured jewels making the back of the throne a grand visual. A parrot cut out of an emerald and the Mountain of Light diamond or the infamous Kooh-i-noor situated in the throne as well. The peacocks symbolise beauty and power as well as immortality. Many praises of the Emperor were inscribed all around the throne in Arabic calligraphy.

The famous traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier recorded in his travels the description of the throne as he was allowed to have an up close view of the Takht-i-Khas. He recorded this account of the throne during the preparations of the Emperor’s annual birthday festival.

The throne had a main seat or mattress-bed which was 6 feet long and 4 feet wide which had four fixed bars at the edges which were about 20-25 inches high. These supported the base of the throne, upon which there were twelve ranged columns holding up a wide canopy; open to three sides facing the court surrounding the throne. They were covered with inlaid gold, diamonds, rubies and emeralds. The middle of each bar held a balass ruby with four emeralds surrounding it making a square cross.The term “balass,” often used in the accounts of rubies, was derived originally from Balkh, in Badakhshan, where there are ancient spinel-ruby mines.

Similar to the square cross, the other side had an emerald cut with four rubies surrounding it. The emeralds were table cut and had almost 10 to 12 carats each. Many parts were set in gold and pearls. The longer side of the throne had a set of four silver-gold steps to ascend it. Surrounding the throne was an array of arms, swords, maces, a shield, bow with a quiver of arrows suspended.

Three cushions decorated the bed of the throne, a round large soft cushion for the Emperor’s back and two large flat cushions placed at his side. The cushions and arms were all covered with fabric and stones that matched the whole glamour of the throne itself. There were 108 balass rubies which were estimated to be at least 100 carats and 116 emeralds. Tavernier states that most of the emeralds were flawed.

The canopy, a quadrangular-shaped dome, encompassing the throne from above, was covered with diamonds and a fringe of pearls all round. A peacock with an elevated tail made of blue sapphires and a body of gold inlaid with precious stones had a large ruby on its breast and a hanging pear shaped pearl. A large bouquet of various different gemstone flowers at the same height of the peacock had a 80 to 90 carat diamond.

The most costly component of the throne remained the extensively studded twelve columns supporting the overhead canopy, surrounded by beautiful rows of pearls. The total cost was around 107,000 lakhs of rupees. Its cost now would have been estimated to 5.5 billion dollars.

The artisans and smiths who worked on this throne are anonymous to history but they were led and supervised by Emperor Shah Jahan and his vision. He was no amateur to these ventures in the fields of art. He conceptualised the throne and carried out the execution of the work. The Timur ruby (352 carats) , the Akbar Shah diamond (95 carats), the Jehangir diamond (83 carats) and the famous Kohinoor (186 carats) adorned the throne. Shah Jahan had his name engraved on some of the large balass including the Timur ruby to etch his name down in history which diminished the ruby’s value but held a lot of dignity for the Emperor.

The Disappearance and Rumours Of The Throne

After an internal struggle with his son Aurangzeb, the Mughal Empire started losing its strength and power due to a high intolerance towards other religions racking up.

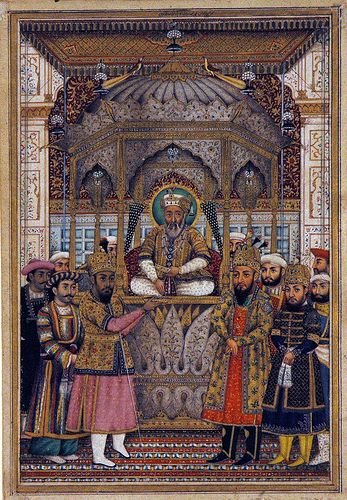

The throne remained as many weak Emperors ascended until 1739. Nadir Shah sacked Delhi and captured the throne for himself.

Nadir Shah was a lowly shepherd who ascended the ranks of the Safavid Dynasty (in Iran) and installed himself as Shah. He later invaded Delhi and killed numerous citizens and forced Emperor Muhammad Shah to give up vast amounts of currency, gemstones, jewels, precious metals and resources.

When he left, the entirety of the Peacock Throne had been taken as well back to Iran. As they proceeded to leave, the rear caravans of Nadir Shah’s loot were attacked by the Sikh armies and a lot of treasures and jewels were recaptured. Unfortunately the Kohinoor and the Peacock throne left India. Proceeding this, he was attacked by the Kurds, a tribe in Iraq. After this incident, there have been no valid documents or records of the Peacock Throne.

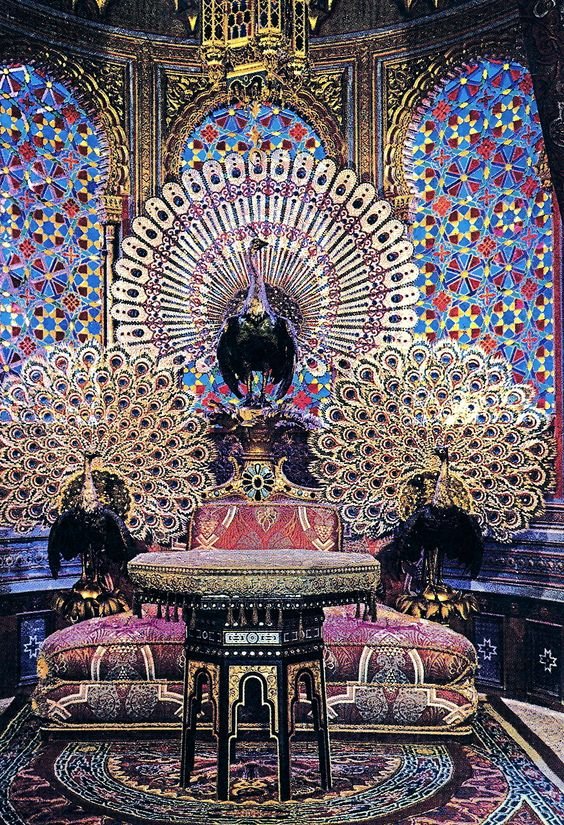

The most logical explanation was that it was dismantled and its jewels were scattered all across Iran. The base legs of the throne were taken back to Iran. The Qajar throne or the Naderi throne was made as a replica to the original Peacock throne and was used for the coronation purposes by two Pahlavi Shahs. Fath Ali Shah also made a reproduction of the throne and nicknamed it “Tavu” or Peacock after one of his wives/concubines.

This throne now sits in the Central Bank of Iran where it is safely kept. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is said to also have potentially discovered a marble leg from the pedestal of the original throne. The throne’s gems are found in numerous jewellery with engravings of Shah Jahan and other Emperors’ names or inscriptions relating to Shah Jahan.

The Kohinoor was found by Ahmad Shah Durrani, the leader of the Afghan nation and was worn by his descendants in the form of a bracelet and then given to the founder of the Sikh Empire, Ranjit Singh.

Not long after, The East India Company annexed the Kingdom of Punjab and took away the loot of Ranjit Singh along with the Kohinoor which now remains with the British Monarchy.

The Last Echoes of The Peacock Throne

The Tahkt-i-Khas was an exemplary work of art for its age and enthralled many generations to come, both Indian and Persian. The Bavarian King Ludwig II made a version of the throne which was overly exaggerated but impressive. This was for his Moorish Kiosk in Linderhof Palace in Germany.

The Peacock Throne’s name rose from being a decorative throne to the name of the entire Iranian Empire which resembled royalty and power as the peacock was a royal bird in Mughal iconography.

The Peacock Throne was the symbol of the Mughal Empire’s Golden age and it represented power and immortality to all of its Kingdom. The epitome of Mughal craftsmanship was visible in the work of the throne. It was a beacon of refinement and cultural diversity with techniques of Persia but recognized Indian elements. The symbolism embedded in every detail of the throne radiated the importance and extravagance. The gemstones, rubies and emerald not only signified the vast wealth but also cosmic and divine attributes in Mughal beliefs.

At long last, this elaborate and ornate throne will be remembered as an architectural triumph screaming the glory of the grandeur and glamour of the Mughal Empire and Age.