Badminton and the Making of a Global Sport

-Oishee Bose

The sport of badminton is not a result of a single invention but the product of countless ordinary decisions made in different places. The game can be read as a social object: shaped by craft, by how people fixed broken gear, by local shops that stocked cheap frames, and by committees that argued over measurements. Over the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries these small practices met larger forces like changing leisure patterns, expanding markets, and new forms of public life and together they produced a sport that could travel beyond a single town or class.

Early shuttle games: objects, markets and everyday practice

Feathered shuttle play is old and widespread. In China, the game now known as jianzi, involved keeping a weighted shuttlecock in the air using the feet. References to similar practices appear in Han and Tang dynasty texts discussing physical training and festival amusements. Archaeological finds and museum-held shuttlecocks made of leather bases and feathers confirm that these were not symbolic descriptions but real, widely used objects. The consistency of design across centuries suggests an established tradition rather than a passing diversion.

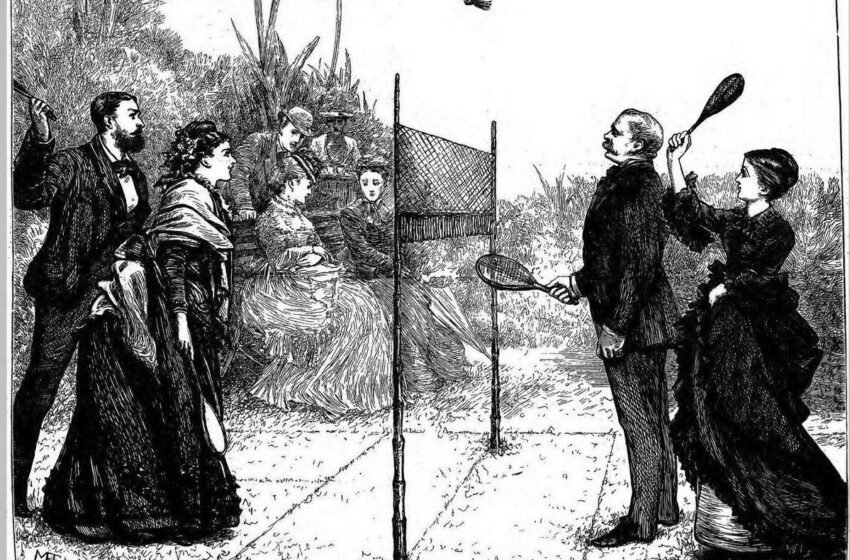

Japan offers a parallel record through the game of hanetsuki. Edo-period woodblock prints depict women and children striking feathered shuttles with wooden paddles called hagoita, especially during New Year celebrations. Many of these paddles survive today, decorated with kabuki figures and seasonal imagery. Temple fair lists from places such as Senso-ji in Edo document the sale of hagoita, showing how play, ritual, and commerce overlapped. These artefacts function as primary evidence of structured shuttle play embedded in everyday life. In Europe the battledore and shuttlecock tradition shows up in children’s manuals and domestic paintings from the seventeenth century onward. These items and images are practical evidence. They show that striking a feathered object was a common leisure activity long before anyone wrote a rulebook.

Poona and the Origins of a Competitive Sport

The modern line of development is easiest to trace in colonial India. Officers who were stationed in the Poona garrison adapted local shuttle play into a net game with competitive scoring. The best dated episode we have is George William Vidal’s note of playing a shuttle game at Satara on 10 July 1873. That entry is important because it provides information about the sport with the mention of a real person, a real place and a real day. The scene in the records is plain: officers off parade, camp chairs or posts used to support a net, and a cork tied with feathers serving as the shuttle. Vidal’s later involvement in Poona circles made him introduce small improvisation to the more organised Poona form that travelled back to England.

How a name stuck: Badminton House and social visibility

Names spread through social networks. The Beaufort estate at Badminton became associated with the pastime because leisure gatherings there featured the game. Estate guides and social notices from the period record country-house entertainments and list the estate among fashionable venues. The sport received more visibility and popularity from this place. Guests who enjoyed the game at Badminton House talked about it in letters and invitations. Over time the estate’s name became the shorthand for the pastime. That is how “badminton” entered general use: not by legal act, but through repeated social reference.

Clubs, argument and the 1893 Laws

Turning informal play into a sport requires agreement. Clubs carried out that work. The Bath Badminton Club kept minute books in the 1870s and 1880s that show debates over net height, court dimensions and what counted as a valid serve. Committee members such as J. H. E. Hart appear in these records as drafters of proposed rules. Those drafts were discussed and adjusted across several clubs. The Badminton Association of England published an agreed set of laws in 1893. The printed laws provided a shared framework and made inter-club contests possible under comparable conditions.

The All-England, 1899: a public stage

A tournament turned private practice into public spectacle. The first All-England Championships took place on 4 April 1899 at the London Scottish Drill Hall in Westminster. Contemporary papers reported the event, paying attention to both the game and the atmosphere. The first tournament emphasised doubles and reflected the club culture from which the game grew. Reporting on the matches created named competitors and gave readers concrete accounts to remember and pass on.

Crafting the Game: Equipment and Makers

Equipment determined what play looked like. Early shuttles were hand-assembled: a cork base, a ring of feathers, glued and bound by small makers. Trade catalogues and period adverts show workshops and small suppliers offering “hand-assembled” shuttles and rattan rackets. Club correspondence sometimes records complaints about inconsistent batches, and invoices in association archives show orders placed by clubs and schools. For competitions to be fair, makers had to deliver reliable objects. Factory production expanded to meet that requirement, producing shuttles and rackets with tighter tolerances, which enabled matches across distant venues to be comparable.

The Thomas Cup: donation, war and a shifted map of excellence

The Thomas Cup began as a donor’s initiative and ended as a global signal of change. Sir George Alan Thomas presented a cup for a men’s international team championship in 1939. Federation minutes record the formal offer and initial planning. The outbreak of the Second World War suspended those plans.

Sport resumed after the war, and the Thomas Cup was contested for the first time in 1948–49. The tournament tested teams that had developed during and after wartime conditions. Malaya won that inaugural contested event. Contemporary reports praised the players’ skill and preparation, and later commentators interpret the result as competitive strength which had shifted beyond Britain and Europe to Asia, serving as evidence of the expanding geographical base. Malaya also celebrated the triumph as a sporting legitimacy and a cultural milestone.

Badminton as a Global Sport

After the Thomas Cup began, badminton slowly became more organised at the international level. New competitions appeared. The World Championships were first held in 1977. The Sudirman Cup followed in 1989 as a mixed team event. These tournaments gave national associations more regular goals. Training became more structured. Junior players were selected earlier and trained for longer periods.

In several Asian countries, badminton moved firmly into schools and state-supported sports systems. Children trained daily and competed regularly. Coaching became a profession rather than a voluntary role. The inclusion of badminton in the Olympic Games in 1992 changed the sport’s position within national sporting systems. Governments began funding it, matches were televised more often, players received institutional support and could train full time. International tours became predictable and prize money increased.

Equipment also changed during this period. Wooden rackets were replaced by composite frames. Shoes and court surfaces improved. Training placed greater emphasis on physical fitness and injury management. Women’s events were held alongside men’s events at major tournaments. Para-badminton later became part of the Paralympic Games. By the late twentieth century, badminton had become a fully organised international sport, while still being played widely in schools, clubs, and local halls.

Conclusion

Badminton’s past shows that durable sports depend less on dramatic invention and more on routine systems: supply chains that deliver reliable equipment, local organisers who maintain schedules and spaces, and informal networks that pass skills from one generation to the next. Paying attention to those systems changes what historians and policy makers look for. It highlights the value of preserving trade records, club minutes and material objects, and it suggests that investment in grassroots infrastructure can have outsized effects on participation and excellence. It also raises questions about credit and memory: whose labour gets named in official histories, and whose work remains invisible in ledgers and scrapbooks? This perspective matters beyond badminton. If we want to understand how sports emerge, spread and become sites of social mobility, we should study the everyday practices that sustain them, and use that evidence to shape how support and recognition are allocated today.