Traditions and Culture Tied in One: Ramlila and Its Origin

-Bhoomee Vats

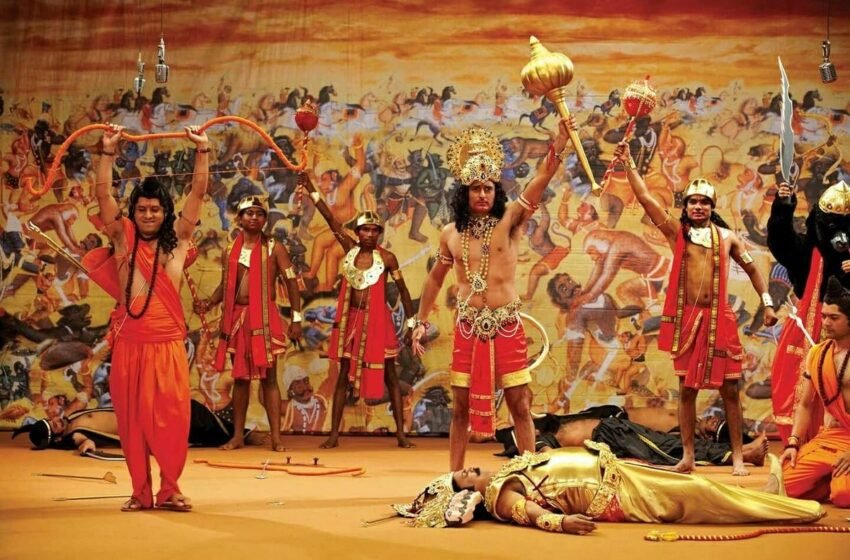

The term ‘Ramlila’ literally translates to “Rama’s play”. It is a performance of the epic of the Ramayana in a series of scenes that does not just consist of acting but also includes song, narration, recitation, and dialogue. It is performed all around northern India during the festival of Dussehra, held each year according to the ritual calendar in autumn after the festival of Navaratri. The most famous and grand Ramlilas consist of places like Ayodhya, Benares, Vrindavan, Almora, Sattna, and Madhubani. The staging of the Ramayana is centred around the Ramacharitmanas and it is one of the most popular forms of storytelling in the north of India. This sacred text, which is devoted to the glory of Rama, the protagonist of the Ramayana, was composed by Tulsidas, a hindu poet, saint, and devotee, in the sixteenth century in a form of Hindi to make the Sanskrit epic available to all.

To celebrate Rama’s return from fourteen years of exile, festivals are organized in hundreds of settlements, towns, and villages during the Dussehra festival season. Ramlila is about the battle between Rama and Ravana and it also includes of a series of dialogues between gods, sages, and the faithful. Ramlila’s dramatic force stems from the succession of icons representing the climax of each scene. Due to the way it is performed, the audience is invited to sing and take part in the narration. The Ramlila brings the whole population together, without any kind of distinction of caste, religion, or age. All the villagers participate with enthusiasm, playing roles or taking part in a variety of related activities, such as tasks like mask and costume making, and preparing make-up, stage, and lights. However, the development of mass media, particularly television and its soap operas, has led to a reduction in the audience of the Ramlila plays, which are therefore losing their principal role of bringing people and communities together.

Versions of Ramlila

Different forms of Ramlila take place in India, some of which are:

- Uttarakhand- Uttarakhand is very rich in cultural traditions. From time to time, many festivals and celebrations are held here. Kumaoni Ramlila is special in this context. Its historical background is more than 160 years old. Kumaoni Ramlila is mainly based on Dohas and Chaupais of Ramcharit Manas and is staged in the Geet-Nataya Shailee tradition. The characters who perform in Kumaon’s Ramlila are common people who become proficient in just twenty days of Taalim. There is social participation in all the work, from the arrangement of stage construction and staging to gathering financial resources. The influence of Parsi theatre is visible in the dialogues, tunes, rhythm, beats, and notes spoken in Kumaoni Ramlila. A mixed glimpse of Braj folk songs and Nautanki is also found in the Ramlila here. In Kumaon’s Ramlila, simple words of the local dialect are used in the dialogues. Various ragas and raginis are used in Ramlila’s sung dialogues. Kumaon’s Ramlila includes the Ramayana singing style of Bareilly’s famous storyteller, Pt Radheshyam. The singing by the characters sounds very pleasant to the ears, with the melodious tune of the harmonium and the resonant sound of the tabla

- Ayodhya– In Mumtaz Nagar in Ayodhya, which has a population of around 1,000 people, with more than 800 of whom are Muslims, local Muslims have been organising the Ramleela for six decades. The mythological Ramleela is staged under the banner of the ‘Ramleela Ramayana Samiti,’ a committee formed by the Muslims of Mumtaz Nagar in 1963 to promote communal harmony. The Ramleela, performed over ten continuous days, features different characters from the Ramayana played by Muslim artists, funded by the Muslim community, and directed by a group of Muslim directors. Reacting to the involvement of Muslims in the Ramleela, Maulana Liyaqat Ali, a cleric in Ayodhya, stated, “It is one of the greatest examples of communal harmony. At a time when Muslims are being targeted for their religion and largely trolled by the media, they have not lost their spirit of harmony. This Muslim Ramleela is proof of our tolerance and belief in brotherhood.”

- Delhi- Delhi is the undisputed epicentre of Ramlila celebrations. The iconic Ramlila Maidan pulls in massive crowds every year, where the tale of Lord Ram unfolds across ten nights of dramatic performance. Equally famous is the Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra (SBKK), known for its acclaimed dance-drama production that fuses classical and folk traditions with polished artistry. The celebrations spill across the city. From the Red Fort grounds, where elaborate stagecraft dazzles audiences, to neighbourhood gatherings in Dwarka and DDA grounds, Ramlila in Delhi feels both monumental and intimate. Once the plays wind down, the city’s melas come alive. Connaught Place and Pitampura buzz with ferris wheels, chaat stalls, and candyfloss, making it as much about food and family fun as about mythology. From here, the festival spirit flows east, into the heart of devotion along the Ganges.

Ramlila of Ramnagar

Started more than 200 years ago by the king of Varanasi, Ramanagar Ramleela is touted to be much older than that. It is believed that the student of Tulsi Das, Megha Bhagat, was the first person to start Ramcharitmanas-based Ramleela in the 17th century. Then Kashi Naresh Balwant Naryan Singh started the Ramleela within the fort premises with unmatchable grandeur and details. Further, King Ishwari Prashad Narayan Singh (1857- 1889) took Ramleela out of the fort among the common people of Kashi & Ramnagar. The 5 Km square area of Ramnagar has been designated Ayodhya, Janakpuri, Lanka, Ashok Vatika, and Cheer Sagar (Pond of Durga temple). The Ramleela has the affectionate patronage of Kashi Naresh even today so much so that Casting of every cast is being done by him. A practice still intact by the modern world and its inventions, the Ramleela of Ramnagar is celebrated for a full 31 days (longer than any other place in the world) in Varanasi.

All the participants start their training 3 months before the actual event, and throughout this time, they are only addressed by the name of their character; even if in private, they live a life just like the character they are playing in the event. The event takes place in different parts of the city without any speakers, mics, or modern lights. The organizers are seen moving with lamps and torches, and the characters are transported from one location to another in a human chariot that devotees pull. There is a peculiarity of Niyamis (the one who regularly attends the Leela). Niyamis carries a source of light, a sitting arrangement, and a Ram Charit Manas. They keep reading the Manas along with the Leela. Niyamis carries Itra with them and greets other fellows with the Itra.