The Art of Metallurgy in India

-Bhoomee Vats

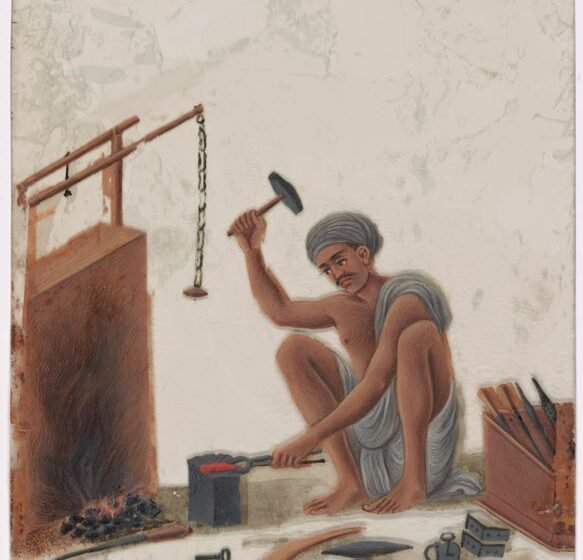

India holds a huge tradition of metallurgical skills hidden in the pages of history for over 7000 years. Metallurgy is not just a skill or a simple activity for India, but a form of art representing one of the most remarkable achievements of its historical civilizations. It reflects a mastery of science, culture, and craft before the rest of the world. Metallurgy is deeply embedded in the system of India, and this can be seen throughout the years, with examples such as that of the earliest use of copper and bronze during the Indus Valley Civilization to the legendary iron pillar of Delhi that did not give in to corrosion for over 1,600 years. Not just this, ancient Indian metallurgists found ways to perform advanced smelting, alloying, forging, and casting techniques, which were often centuries ahead of their Western counterparts. The knowledge was not just limited to making tools, weapons, and ornaments, but also in creating monumental architecture and religious art. This gave metallurgy a high place in not just the socio-economic but also the spiritual life of the country. India’s long-lasting tradition of metallurgical art and skill shows how science and society went hand in hand and played a huge role in the country’s past. This craft not only fulfilled the needs of warfare, trade, and even agriculture but also carried a huge symbolic value by representing prosperity and the value of art. Hence, the legacy of Indian metallurgy is not just about technical and scientific brilliance but also about culture and showcasing how art, skill, and scientific inquiry were successfully and harmoniously blended in the making of civilization.

Important sources for the history of Indian metallurgy

Archaeological digs and literary evidence are the two most important sources for the history of Indian metallurgy. The first evidence of metal in the Indian subcontinent was discovered in the Balochistan town of Mehrgarh when a little copper bead dated to around 6000 BCE was discovered. It’s believed to be native copper, which wasn’t removed from the ore. Copper metallurgy in India dates back to the Chalcolithic societies in the subcontinent, according to spectrometric tests on copper ore samples discovered from ancient mine pits at Khetri in Rajasthan and metal samples cut from representative Harappan artefacts unearthed from Mitathal in Haryana. Indian chalcolithic copper items were almost certainly manufactured on the continent.

Chalcopyrite ore resources in the Aravalli Hills provided the ore used to extract metal for the artefacts. The Archaeological Survey of India produced and released a collection of archaeological literature from copper plates and rock inscriptions throughout the last century. Copper plates were used to engrave royal records. Famine relief attempts are mentioned in the earliest known copperplate, a Mauryan record. It contains one of India’s few pre-Ashoka Brahmi inscriptions. Gold and silver were also used by the Harappans, along with their own alloy, electrum. In ceramic or bronze pots, various ornaments such as pendants, bangles, beads, and rings have been discovered. Indus Valley sites such as Mohenjo-Daro have yielded early gold and silver jewellery.

Disappearance of Metallurgical Skills

India’s prosperity was drastically harmed during the period of Turkish invasion. Turkish rulers carried away the country’s riches to Islamic countries and enslaved men, women, and artisans. In the Mughal period, surviving artisans in the country’s remote places were patronized and resettled in new places. Under the Mughal patronage, the iron workers of Gujarat and Deccan began making forged iron guns, firearms, and various war weapons and armours. Cottage iron making was flourishing by the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The iron production was taking the shape of an organised industry. In 1852, Oldham reported working 70 iron-making furnaces in Birbhum district. These large furnaces could produce 2 tonnes of iron per furnace at the cost of `17 only. However, these industries could not last long. The British representatives took over the local industries. In spite of the better quality of Indian iron and steel, they began to import British and Swedish iron and levy a heavy tax on local produce. European and British governments established their own industries. The British government began exporting high-grade iron ore from India to supply raw material to these industries and banned iron and steel-making in India. The British government also began to import finished iron and steel machinery and levied high taxes on the Indian produce. Thus, the tribal art of iron and Wootz steelmaking was almost stopped. A similar fate was that of zinc production.

Conclusion

Even after being prevalent and important for so many centuries, metallurgy as a skill in India tells the story which is of both loss and excellence. Indian artists continued to portray their unmatched mastery in shaping and refining metals to create something beautiful for more than 7000 years. Some of the major works of this art can be considered the copper beads of Mehrgarh, the gold ornaments of the Harappans, the unmatched strength of Wootz steel, and the grandeur of Mughal weaponry. These works showcase the ability of Metallurgy as a skill to stand as one of the centre stones of the civilization of India. However glorious, this tradition also faced the suffering which was caused due to continuous invasions and colonial exploitation. Even though the Mughals tried to preserve certain crafts in the name of royal patronage, with the arrival of the British, many industries that revolved around handiwork, art, and the skills of the artists crumbled under the weight of huge taxation and bans. The decline of India’s metallurgical skills was not essentially due to a lack of knowledge, skill, or quality but due to deliberate suppression of native enterprise.

Nevertheless, the legacy of Indian metallurgy endures in monuments, artifacts, and historical records that continue to inspire scholars, scientists, and artisans alike. It serves as a reminder of India’s long-standing scientific and artistic achievements, as well as the resilience of its people in safeguarding cultural memory despite adversity. In rediscovering and reviving these metallurgical traditions today, India can not only honor its past but also harness its heritage to fuel innovation for the future.