The Evolution of Women in Cinema: From Silent Shadows to Leading Lights

-Anushka Sengupta

→ Trace the portrayal of women through landmark films like Mother India, The Color Purple, Queen, and Everything Everywhere All at Once

As both external and internal mirrors of society, cinema has consistently reflected and influenced society’s conceptions of gender, power, and identity. This is a massive leap forward for the portrayal of women in film, from damsels in distress to fully fleshed out leading ladies who propel the story forward. This essay outlines how these representations of women have changed by looking at four seminal films from around the world, spanning several cultures and centuries — Mother India (1957), The Color Purple (1985), Queen (2013), and Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022). From their varied geographical roots to their distinctive visual narratives and multifaceted female characters, these films are testaments to the evolving portrayal of womanhood on screen, each being a landmark stepping stone toward new horizons of female empowerment, agency and identity.

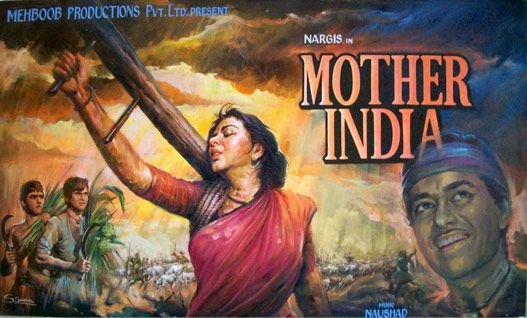

Mother India, directed by Mehboob Khan, is an iconic landmark in early post-independence Indian cinema with international recognition. The film narrates the story of Radha, a poor village woman who endures immense hardship and personal sacrifice in the face of injustice, poverty and social expectations, refuses to conform yet upholds responsibility towards her ethics and familial structure to restore social justice. She is the embodiment of the closely-held, idealized “Bharat Mata” (Mother India) – a Hindu goddess-like representation that is often used to evoke the greater Indian spirit. She is strong, resilient and self-sacrificing. As for Radha, in Mother India she is no longer the mute heroine but the architect of action and captain of narrative. Her power is constantly limited by being cast within a narrative of suffering and martyrdom. Consequently, she turns into an exemplar of the self-sacrificing maternal ideal, the woman who gives up her own wants and needs for the welfare of her household and neighborhood. Even in this forward-thinking cinematic marvel, women can’t escape the patriarchal structures of society that judges their worth by the extent to which they can endure the suffering in silence. While this portrayal was indeed progressive for its time, it demonstrates early female representation in film—from women being portrayed as saviors, but only in the domestic and moral sphere.

Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple, adapted from Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, goes beyond that and takes a significant leap, detailing the experiences of African American women who were twice made invisible by the forces of racism and patriarchy in early 20th century America. Indeed, the creativity of the adaptation matches the quality of their substance. Celie, the protagonist of the novel, starts off as an invisible, voiceless and abused child and finishes as a self-reliant woman capable of claiming her own narrative, emerging from it all with liberation and redemption. While Mother India proudly waved the banner of and glorified women’s sacrifice, The Color Purple is a story of reclamation and awareness of one’s own agency and autonomy. Out of every journey, Celie’s might be the most personal one. She frees herself not just from the men who see her as property, but from the internalized self-hatred that comes with the idea that she is of no worth. As a result of sisterhood, letters, and spiritual awakening, Celie evolves from a timid, overpowered spirit to a majestic, radiant presence. The film incorporates feminist narrative undertones where women are not just vessels of reproduction or symbols of endurance, they are vessels of their own liberation. By placing Black women at the center of the story, it challenged the mainstream cinema, emphasizing personal empowerment over moral martyrdom.

Vikas Bahl’s Queen, released in 2013, crystallized a new wave of liberated, feminist storytelling to such a degree that it became a touchstone within Indian cinema. In this film, the narrative’s main character, Rani, is abandoned by her future husband just days before their wedding ceremony. Determined on avoiding shame, she reclaims her passion for travel and goes on their planned honeymoon alone, entering a more enjoyable and freeing adventure throughout Europe. As is made clear over the course of Rani’s journey, this transformation in her spirit is quiet yet profound and progressive. Her rebellion is not through drugs or the conventional sense of the word but rather through life changing experiences that are the exact opposite of her orthodox upbringing as she rediscovers happiness, liberation and self-esteem. While Queen is sprawling over a landscape that is culturally dynamic and emotionally rich, it keeps a buoyant tone that allows it to face complex questions around identity and autonomy. It compels the Indian female protagonist to be independent, adventurous and self-loving. Like Mother India, Queen places its protagonist at the center of the storm. Unlike Mother India, the film does not place its female lead in the familial structure of a martyr. Unlike The Color Purple, it’s not centered on healing trauma caused by an oppressor. It rather keeps going back, time and again, to the centrality of a simple, profound truth—the choice to love yourself. This is a reflection of a world where more women are free to choose who they want to be against the patriarchal backdrop.

The Daniels’ Everywhere All at Once presents one of the most radical portrayals of womanhood in modern cinema. Evelyn Wang, an elderly, overwhelmed Chinese-American laundromat owner, finds she must save the multiverse at the heart of this absurd multiverse trip amid family conflicts, generational trauma, and her own feelings of inadequacy.Evelyn’s complexity sets her apart. She is profoundly human, imperfect, weary, not a young rebellious or idealized mother. Rather than a straight narrative of empowerment, the movie examines female identity through a kaleidoscope of possibilities—each version of Evelyn exposes a different potential life route. By embracing these contradictions, Everything Everywhere All at Once breaks fresh ground; it implies that empowerment comes not from overcoming one’s flaws but from accepting them. Furthermore, the film is groundbreaking for its intersectionality—that of race, immigration, and queerness next to gender. It shows a modern mindset that embraces diversity of experience and understands there is no one way to be a woman.

As shown in these four movies, the development of women in cinema shows a great change from symbolic images to multidimensional realities. From Evelyn’s chaotic humanity in Everything Everywhere All at Once to Radha’s resolute sacrifice in Mother India, female characters have progressively shifted from the fringes to the very center of the narrative—and more notably, they have been free to grow, dream, and set themselves apart on their own conditions. This transformation mirrors societal changes and continuing fight for gender equality. Although progress has been made, the depiction of women in film keeps changing, molded by new voices, varied experiences, and an ever-widening concept of what it means to be a woman on screen. The leading lights of the future will surely shine bright as cinema keeps mirroring and transforming our knowledge of the world.