History of Sawan Kanwar Yatra and Its Significance

-Anushka Sengupta

India, with its rich spiritual heritage and cultural traditions, boasts innumerable festivals and pilgrimages that constitute the essence of its religiosity. Of these, the Kanwar Yatra in the holy month of Shravan or Sawan (July–August) occupies a special space in Hindu lore. Every year, millions of such devotees, called Kanwariyas, make this pilgrimage to bring back holy water from sacred rivers and worship it onto Lord Shiva. The yatra is not merely a ritual. It is an intertwining of mythology, asceticism, fellowship and heritage.

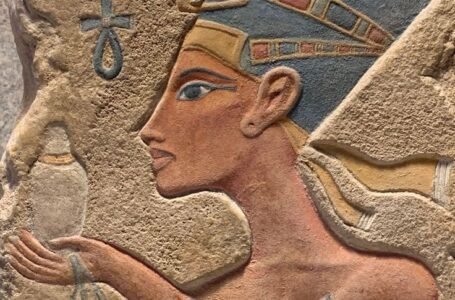

The roots of the Kanwar Yatra are steeped in Hindu folklore. One of the ancient allusions is in the legend of Samudra Manthan–the celestial churn of the ocean. When the lethal poison Halahal materialized, Lord Shiva gulped it down to save the world. To ease the agonizing poison’s burn, devotees started pouring water from holy rivers like the Ganga to Shiva — a practice that became the Kanwar Yatra. Another significant connection is from the Ramayana, when Lord Rama is said to have presented Ganga water to Shiva at Deoghar’s Baidyanath temple. In the same vein, the myth of Parashuram (an avatar of Vishnu) who had presented Ganga water to a Shivalinga in atonement lends additional credence to the ceremony’s provenance. Combined, they enrich the symbolic and spiritual landscape of the yatra, underscoring themes of thanksgiving, repentance and cleansing.

Kanwar Yatra is an extraordinary pilgrimage where devotees carry river water, especially the Ganga, using a kanwar, a bamboo pole with pots filled with water on either side. These are hung from the shoulders as the pilgrims trek barefoot, chanting “Bol Bam!” in idolatry of Shiva. The yatra typically concludes at a Jyotirlinga or a Shiva temple, where the jal is ceremoniously presented to the god. Some of the great destinations are Haridwar, Gaumukh, Sultanganj, Deoghar, and others. The yatra is not simply an individual ascetic practice, but a shared act of faith, community, and sacrifice.

Historically, Kanwar Yatra was a local affair observed by a few ascetics residing in close proximity to Ganges. In antiquity, it was largely the domain of ascetics and villagers. It was during the medieval period with the expansion of Shaivism and the establishment of major Shiva temples that pilgrimage attracted a broader following. Fast forward to the present day, and the Kanwar Yatra has become one of the biggest annual religious congregations on the planet over the last several decades. With the spread of roads and connectivity, millions now come from UP, Bihar, Jharkhand, Haryana, Rajasthan and Delhi. The pilgrimage had therefore evolved beyond a mere religious observance to a wild socio-religious spectacle.

Spiritually, the yatra is intertwined with the month of Sawan, sacred for Lord Shiva. That they are absolved of their sins and brought closer to moksha by offering Ganga water during this month. Pilgrims observe austerities on the journey. They shun non-vegetarian food, alcohol and other earthly pleasures. So walking barefoot for days is a test of faith, it’s an act of surrender. The pilgrimage unites communities, with langars, resting stations and medical camps arranged by the locals and volunteers. Thus the yatra reaffirms social cohesion and common religiosity. The Kanwar Yatra is about cleansing and rejuvenation. Carrying water from the river becomes a metaphor for carrying the load of one’s suffering and casting in at the feet of god. Sprinkling water on Shiva indicates the release of ego, desires, and sins. Economically as well, the pilgrimage is important. Small businesses thrive along the paths, and the towns that host pilgrims benefit from increased commerce, hospitality, and cultural trade.

These are the primary routes of Kanwar Yatra – Haridwar to Neelkanth Mahadev, Rishikesh, Sultanganj to Baidyanath Dham, Deoghar and Varanasi to Kashi Vishwanath Temple. Every route is bathed in orange flags, music systems and decorated stalls rendering a festive but devotional atmosphere. With these facilities around, the journey remains feasible even for a novice pilgrim. Even with its spiritual significance, the Kanwar Yatra is not without its hardships. The sudden presence of huge crowds frequently causes traffic problems, garbage and security challenges. Even in recent years, states like Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand have led the way by deploying police, organizing cleanliness drives, installing CCTVs and medical support. Such endeavors seek to preserve the holiness of the pilgrimage while coping with the logistical strain of such a massive congregation.

Ultimately, the Sawan Kanwar Yatra remains an ageless homage to faith, humility, and communal spiritual journey. Steeped in ancient mythologies and nurtured by the steadfast devotion of millions, it is still one of India’s most vital spiritual traditions. In our age of rapid lifestyles, the yatra not only resurrects spirituality but re-establishes the importance of perseverance, humility and sewa. A living tradition, part myth and part ordinary belief, it reminds us of the eternal connection between man and God. The oldest textual mentions of water offering during Sawan is found in texts like the Skanda Purana and Shiva Purana, which highlight the virtue of worshipping Lord Shiva with water and bilva leaves in this month. These Puranic texts set the stage for eventually-organized pilgrimages. Others believe the practice was once tied to primitive Shiva cults that flourished in the Gangetic plains and Himalayan foothills, where tanks were venerated as incarnations of the goddess.

A few centuries ago, the Kanwar Yatra was a small-scale event. Ascetics and hermits that lived with austerity were the main actors, striding solo or in small clans to splash nearby Shiva shrines with water. Over the centuries as temple architecture blossomed under the sponsorship of regional dynasties like the Guptas, Palas and Chandelas, so did the number of Shiva temples and devotees. In medieval times, particularly with the emergence of Bhakti movements, devotion to Lord Shiva became more democratized. Saints such as Tulsidas, Kabir and Ravidas promoted personal devotion over ritualism, rendering pilgrimages such as the Kanwar Yatra more accessible and communal. By the late 20th century, the Kanwar Yatra had become a mass movement. With better transport and communication and televangelist sermons and songs the pilgrimage boomed. Today, the likes of UP, Bihar, Jharkhand, Haryana, Delhi and Rajasthan see millions of Kanwariyas descend. It is a manifestation of life and faith bursting out in colorful processions, thundering bhajans and camps emblazoned with slogans on the magic of the pilgrimage and the glory of Lord Shiva—a massive display of religious fervor.

Spiritually, the yatra is intimately connected with the month of Sawan which is astrologically associated with increased spiritual sensitivity. There is a belief that if we offer Ganga water to Shiva in this month, it washes our sins and gives Mukti. Worshipers maintain rigorous vows of abstinence, celibacy, and humility. The barefoot journey of hundreds of miles is its own form of sacrifice, a corporal atonement and spiritual cleansing. The continuous recitation of bol bam serves not only as an expression of devotion, but as a meditative mantra that keeps the pilgrim’s spirit alive. Culturally, the Kanwar Yatra is a great leveler. Strangers, from different regions and castes and economic backgrounds, walking shoulder to shoulder, breaking bread in roadside langars, sleeping under the same tarps roofs, lending each other a hand on the route. The pilgrimage generates group cohesion, altruism, and social cooperation. Community kitchens, volunteer camps and free health check ups en route mirror the seva (service) streak of Hindu spirituality.

On the economic front, the yatra invigorates local commerce. Food, religious items, clothes and souvenirs are sold by vendors. Transportation services flourish and temple towns see an increase in tourism. This seasonal influx of people drives economic activity to otherwise rural and small-town areas. The major routes of the Kanwar Yatra include: Sultanganj (Bihar) to Baidyanath Dham (Deoghar, Jharkhand) – about 105 km walk. Haridwar, Gaumukh, Gangotri to Neelkanth Mahadev (Rishikesh, Uttarakhand) – a well-known Himalayan trail. Haridwar to local temples in Delhi, Meerut, Muzaffarnagar and other cities in UP and Haryana. Varanasi to Kashi Vishwanath Temple An important city route where ancient traditions mix with contemporary worship.

To handle the modern scale of it, local governments have set up elaborate police and emergency services, traffic diversions and waste management schemes. The pilgrimage remains amazingly peaceful and disciplined, thanks to the devotion and cooperation of the pilgrims themselves. Overall, the Sawan Kanwar Yatra is more than a religious pilgrimage — it’s a profound declaration of devotion, tradition, and spiritual awakening. Rooted in ancient mythology and honed by centuries of tradition, the yatra continues to attract millions in a ritual of devotion that defies regional and social barriers. In a world ever more individualistic and consumerist, the yatra teaches us about the power of communal faith and the human longing for purification, for the eternal quest to unite with God. It remains a tribute to the ancient spiritual soil of India, a soil where legends turn to ceremonies and ceremonies turn to living.