Nāth Sampradāya and the Synthesis of Shaivism and Tantra

The Nāth Sampradāya is a Shaiva tradition , which is a blend of yoga, tantra, and devotional practices. At its core, the tradition venerates Śiva as Ādinātha, the “First Nāth,” who serves as the primordial teacher. It traces its roots to Matsyendranātha, a 9th–10th century yogi credited with introducing tantric and yogic principles, and Gorakṣanātha, a 12th-century reformer who formalized the ascetic order. Over time, the Sampradāya evolved into two branches: the ascetic Nāths, who renounce worldly life to pursue monastic practices, and the householder Nāths, who live within familial structures while upholding Nāth traditions and practices.

Early Development

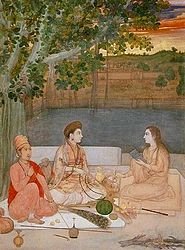

The Nāth Sampradāya emerged from the Siddha tradition, an ancient lineage that emphasizes spiritual and physical transformation. The Siddhas focused on disciplines such as yoga for mental and physical mastery, alchemy for personal transformation, and tantra for esoteric and mystical practices. Two pivotal figures shaped the Nāth Sampradāya: Matsyendranātha and Gorakṣanātha.

Matsyendranātha is associated with Kaula Tantra and its ritualistic teachings and is considered the founder of the Nāth Sampradāya, having received teachings from Shiva.

According to legend, Matsyendra was born beneath a bad star. Therefore, his parents tossed him into the sea because of this. The infant stayed there for several years after being ingested by a fish. When Shiva was teaching his consort Parvati the mysteries of yoga, the fish swam to the ocean’s bottom, and Matsyendra started doing yoga sadhana inside the fish’s belly after learning the mysteries of yoga. He became an awakened Siddha after twelve years. There are several versions of the story.

Another pivotal figure is Gorakṣanātha, who refined these practices and established Hatha Yoga as a central discipline. The myths about his birth emphasize his otherworldly nature, with some believing he was not born in the usual sense but manifested from the cosmic realm, reflecting his transcendence over time and space.

Gorakṣanātha’s legendary journey begins with his connection to his teachers, notably Ādinātha and Matsyendranātha. He is often depicted as receiving his spiritual knowledge directly from Shiva, with Ādinātha being the first teacher in this divine lineage. Gorakṣanātha’s teachings were said to have transcended traditional metaphysical debates of his time, focusing instead on practical yoga and the direct experience of spiritual truth. He is often described as a figure who broke free from the constraints of societal norms, rejecting the dualistic and non-dualistic philosophical debates of his time in favor of direct, experiential practice.

He is believed to have had the ability to perform miracles, including controlling the elements, healing the sick, and even manifesting at will. These stories contribute to his status as a great yogi and Maha-yogi. One of the popular legends involves Gorakṣanātha using his yogic powers to bring balance to the world and guide his disciples through difficult challenges.

Early Texts and Iconography

The Nāth Sampradāya’s earliest references are found in inscriptions, texts, and artistic depictions dating back to the 9th to 15th centuries. These materials reveal the widespread presence of Nāth-like yogis and their spiritual practices across regions like the Deccan and eastern India. Prominent sources such as Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka and Tibetan accounts of siddhas highlight the prominence of figures like Matsyendranātha, revered for their expertise in esoteric yoga and tantric rituals. This early period reflects the Sampradāya’s deep roots in mystical and ascetic traditions, setting the stage for its later development.

Organized Structure

the Nāth Sampradāya functioned as a loose network of yogis and Siddhas for centuries,but by the 17th century, the Nāth Sampradāya had evolved into a well-organized tradition, transitioning from its earlier informal network of Siddhas and yogis. This formalization introduced a division into twelve panths (paths), which represented diverse regional and doctrinal lineages. The establishment of these paths provided a unified framework for the tradition, enabling it to extend its spiritual influence across the Indian subcontinent and solidify its cultural and religious identity.

Branches of the Nāth Sampradāya

The Nāth Sampradāya is composed of two distinct branches that reflect different approaches to spiritual life: the ascetic Nāths and the householder Nāths. Despite their differences, both branches share a commitment to the tradition’s core values of devotion, discipline, and spiritual growth.

The ascetic Nāths embody the monastic ideal, renouncing worldly attachments and dedicating their lives to rigorous spiritual practices. They pursue a path of meditation, tantric rituals, and yogic disciplines such as Hatha Yoga, aiming to achieve self-mastery and spiritual enlightenment. Their renunciatory lifestyle is a hallmark of the tradition, emphasizing detachment and inner transformation.

In contrast, the householder Nāths integrate Nāth principles into everyday life while maintaining familial and social responsibilities. Spread across India and Nepal, they focus on preserving the oral traditions of the Nāth Sampradāya through devotional singing and storytelling. Their practices, such as performing bhajans and narrating Nāth legends, ensure the continuity of the tradition within a broader community context.

These two branches highlight the versatility of the Nāth Sampradāya, allowing both ascetics and householders to contribute to the spiritual and cultural legacy of the tradition.

Key Rituals and Symbols

Rituals and symbols are central to the identity of the Nāth Sampradāya, with unique practices that distinguish both ascetic and householder branches.

- Hooped Earrings (Kānphatā): Ascetics are known for their large, hooped earrings inserted into cartilage slits during initiation. These symbolize their renunciation of worldly attachments and commitment to spiritual discipline.

- Sīṃgnād Janeū: A sacred thread adorned with a small horn, a rudrākṣa seed, and a flat ring, worn around the neck. This thread signifies adherence to the Nāth tradition and is used in ritual practices.

- Pātradevatā: A sacred pot containing key Nāth symbols, including earrings, a rudrākṣa bead, and a chillum (smoking pipe). This pot is central to Nāth worship, serving as a repository of the tradition’s spiritual insignia.

Regional Spread and Influence

The Nāth Sampradāya has a broad geographic reach, influencing various regions across the Indian subcontinent.

South India

The Kadri Monastery in Karnataka is among the oldest Nāth centers, associated with Matsyendranātha and early tantric teachings. Many foundational texts on Hatha Yoga also trace their origins to the Deccan region, highlighting the area’s role in shaping the tradition.

East India

The Nāth tradition emerged in Bengal and Assam as early as the 13th century. However, it gained a more organized presence only by the 18th century, with householder Nāths playing a key role in its preservation and propagation.

Nepal

The Nāth Sampradāya holds a significant place in Nepal’s cultural and religious history. Inscriptions from the 14th century mention Nāth yogis and their influence in unifying Nepal. Gorakhnāth, a central figure in the tradition, is revered as a protector deity and continues to be a symbol of spiritual and political power in Nepal.

Northwest India

In Punjab, Nāth centers like the Jogi Tilla Monastery have historically been influential. The Nāths also played an instrumental role in the Himalayas, contributing to local politics and religious developments, particularly through figures like Jālandharnāth.

Practices and Doctrines

At the heart of the Nāth tradition lies a distinctive blend of spiritual practices aimed at achieving liberation (moksha) and union with the divine. The primary methods include Hatha Yoga, Tantra, and devotion, each of which serves a unique role in the practitioner’s spiritual journey.

Yoga, particularly Hatha Yoga, is a cornerstone of Nāth practice. Hatha Yoga emphasizes physical discipline as a means of attaining spiritual enlightenment. The tradition’s focus on postures (asanas), breath control (pranayama), and meditation is believed to purify the body and mind, facilitating deeper spiritual experiences. Although the practice is less commonly followed by Nāths today, it remains an essential element of their tradition, contributing to the overall health and well-being of practitioners.

Tantra, another important facet of Nāth spirituality, involves esoteric rituals and the worship of deities, particularly goddesses. Tantric practices are often considered secretive and are meant to unlock hidden spiritual potential. This form of worship involves intricate rituals designed to awaken and harness the power of the divine, often through the use of mantras, yantras, and other sacred symbols. The emphasis on goddess worship within the Nāth tradition is seen as a means of connecting with the feminine aspect of the divine, which complements the Shaiva principles of masculine power.

In addition to these esoteric practices, the Nāth tradition incorporates elements of Bhakti—devotion to the divine. Bhakti has had a significant influence on daily worship among Nāths, blending devotional practices with the more mystical and esoteric aspects of Tantra. This combination of Tantra and Bhakti allows for a holistic approach to spirituality, emphasizing both personal devotion and the cultivation of deeper spiritual knowledge.

Key Teachings and Philosophical Goals

The core goal of the Nath tradition is the pursuit of liberation (moksha or jivan-mukti) while alive, a concept known as paramukti, which is achieved through deep yogic practice and self-realization. Gorakshanatha’s teachings emphasize the idea that spiritual freedom is attainable through self-discipline, meditation, and living a virtuous life. According to contemporary Nath Gurus like Mahendranath, the ultimate aim is not only to achieve spiritual liberation but also to avoid rebirth, thus escaping the cycle of reincarnation.

The Nath yogis also reject the traditional caste system, which they see as an artificial social construct. Gorakshanatha, in his writings, proposes a more inclusive framework based on the practice of the 64 arts (kalas), advocating for the transcendence of caste distinctions in favor of spiritual practice and self-realization.

Practices of Hatha Yoga and Influence on Other Traditions

The Naths are known for their early contributions to the development of Hatha Yoga, a discipline focused on physical postures (asanas), breath control (pranayama), and meditation techniques. Texts like the Vivekamārtaṇḍa and Gorakhshasataka are among the foundational works of Hatha Yoga, often attributed to Gorakshanatha. These texts influenced other philosophical schools, including Advaita Vedanta, and are believed to have shaped the broader yogic and mystical traditions in India.

Additionally, the Naths played an important role in the development of the Vaishnavite and Sufi traditions, particularly through their acceptance of Muslim yogis into their fold. The Naths’ inclusive approach allowed them to bridge religious divides, and their practices have influenced both Hindu and Sufi mysticism.

Distinctions from Other Orders

The Nāth tradition is distinctive in several ways, particularly in contrast to other ascetic and religious groups in India. Unlike the militarized ascetic groups, such as the Daśanāmī Sampradāya, the Nāths do not adopt weaponry or engage in warfare. Their practices and rituals prioritize non-violence (ahimsa) and spiritual purity, setting them apart from more militant ascetic orders. The Nāth tradition also distinguishes itself through its unique symbols, such as the tilak (a mark worn on the forehead) and the trident (trishul), which represent the power and divine energy of Lord Shiva.

Additionally, the Nāths’ practice of focusing on internal spiritual development—rather than external displays of strength or prowess—further defines their separation from other Shaiva orders. The Nāths’ non-violent, introspective approach to spirituality, combined with their emphasis on self-discipline and the pursuit of inner truth, positions them as a distinct and influential force within the broader Hindu tradition.

Decline and Modern Adaptations

Like many religious and spiritual traditions, the Nāth order faced significant challenges during colonial rule in India. The impact of British colonization was especially felt by ascetic orders like the Nāths, who were suppressed and marginalized as part of the broader effort to control indigenous practices. As a result, many Nāth practitioners were forced to adopt household lifestyles to survive, and the traditional practices of the order declined.

However, the Nāth tradition has experienced a resurgence in modern times, primarily due to efforts by organizations like the Yogi Mahasabha. This group has worked to preserve Nāth teachings, revitalize traditional practices, and create awareness of the importance of the Nāth tradition in contemporary spiritual discourse. Despite the decline in active practitioners, the tradition continues to influence yoga and spiritual movements around the world, with many of its teachings being incorporated into modern wellness practices.