The Sacred Ghats of Varanasi: A Historical Testament Throughout the Ages

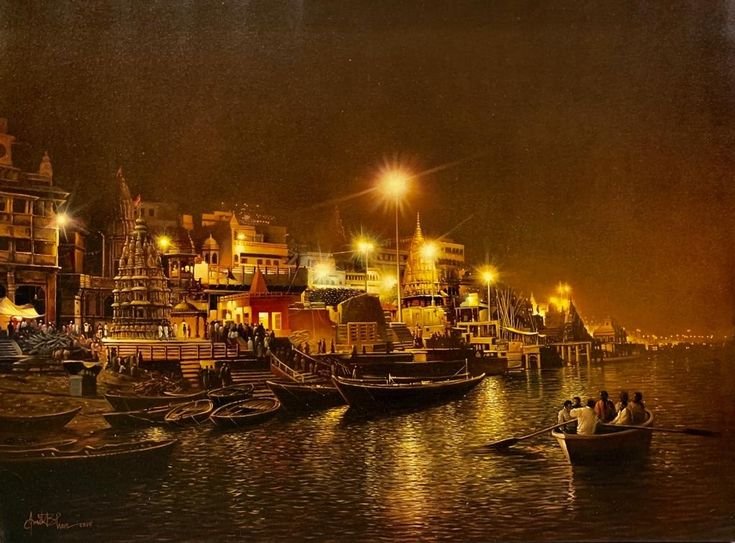

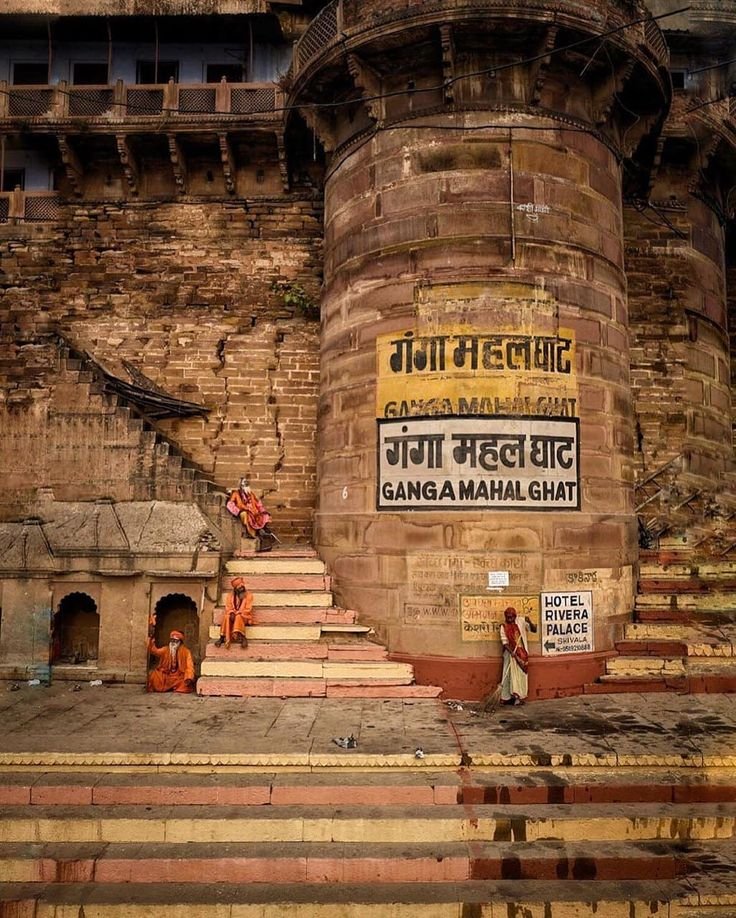

Acting as a quintessential representative of India’s spiritual legacy, Varanasi, also referred to as Kashi or Banaras by the local populace, belongs to the world’s oldest cities measured in terms of continuous habitation. After thousands of years of religious, cultural, and philosophical evolution, it is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities. Most importantly, the actual identity of the place revolves around its ghats-gently sloping banking along the sacred Ganges River. With an impressive figure of more than 80 ghats, they amply represent the spiritual linchpins of the city where acts of life, death, and rebirth continue like an unbroken thread.

Varanasi’s ghats are not just mere inanimate constructions; rather, they symbolize frames into realms of transcendence. They become prayerful, meditative, and salvific sites so integrally bound with the Hindu belief in the Ganges’ holiness and its capability of purging sins. Over the centuries, history, mythology, and culture have shaped and moulded these ghats into potent representations of India’s spiritual ethos.

History of Varanasi Ghats

The earliest initiation of Varanasi’s ghats, according to some sources, lies in the remote history of the city that goes back about three millennia. Varanasi referred to in the Rigveda, one of the most ancient texts of the world, is said to be a site of outstanding spiritual significance. The ghats developed naturally, complementing the pilgrimage role of the city, and facilitating access to the sacred waters of the Ganges.

The ghats, along with the riverbanks, used to be informal bathing rooms for pilgrims, where they would wash themselves of sins and then seek blessings for their further journeys. This riverfront gained prominence during the Gupta period (from the 4th to the 6th centuries CE), where it featured in religious ceremonies such as yajnas (fire rituals) and shraddha (offerings to ancestors). The construction of decent proper ghats probably started in this period with help from kings and affluent merchants.

In the medieval periods, the ghats were expanded and developed, as different kings and benefactors commissioned various buildings to enhance their spiritual and architectural significance. The Mughal, Maratha, and Rajput houses constitute the most important dynasties that fashioned the ghats of today. The Marathas also contributed the most in the 18th century, involving queens like Ahilyabai Holkar, who reconstructed a number of the ghats that had fallen into disrepair.

The Mythology and Spiritual Significance of the Ghats

Hindu mythology creates a very deep spiritual significance for the ghats, hence rendering them something more than mere architectural features. In the ancient texts, the Ganges River descended to the Earth through prolonged efforts of King Bhagiratha to purify the ashes of his ancestors in the quest for liberating them (moksha). This cosmic act made the river symbolic of divine grace as well as made the ghats easy paths towards liberation.

One of the most famous is Manikarnika Ghat. It is said to be the place where the earrings of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati fell; hence, it is considered sacred for cremation rites. It is believed that performing the last rites here liberates the soul from the cycle of birth and death.

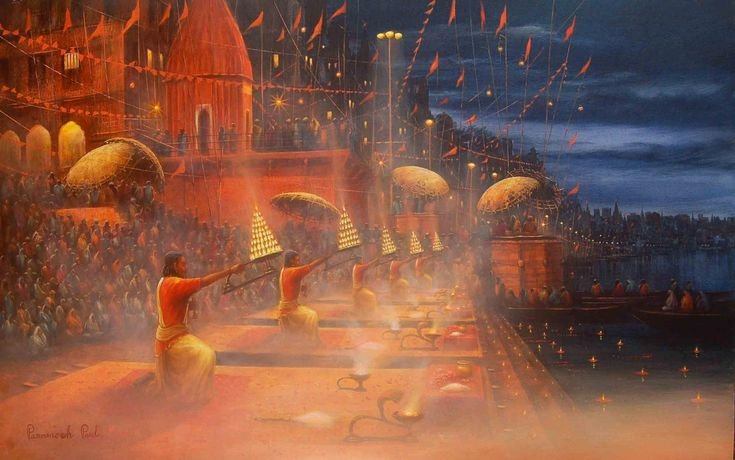

Dashashwamedh Ghat, another made ghat, is connected to the myth that Lord Brahma conducted snake horse-based offerings (aswamedhas) to welcome Lord Shiva to Varanasi. This ghat is extremely vibrant and represents the hub of daily Ganga Aarti which attracts tourists and pilgrims alike.

Another mythologically significant Ghat is the Panchganga Ghat, where five rivers are said to have converged. Devotees can enjoy the blessedness of several holy rivers together, for it is the place where many sages underwent severe penances.

These mythological stories add divine authenticity to the ghats, re-establishing their status as the sacred space that connects the mundane with the divine.

Architectural and Cultural Evolution of the Ghats

The construction of the ghats reflects a complex conjunction of architectural influences over the years. Built principally of stone, the ghats descend from the land into the water and are generally formed with steep steps. The ghats are characterized by temples, pavilions, and shrines that, while separate, create a visual whole under their diversity of creative processes extended to merge spiritual interest with art forms.

Many ghats get their names because the rule was built or reformed by some rulers or benefactors. For instance, Kedar Ghat was built on the initiative of the Maharaja of Vijayanagar, while Scindia Ghat indicates a contribution from the Scindia dynasty. Rajasthan’s Rajput kings also had their share of contributions by building ghats, like Harishchandra Ghat, after that legendary king Harishchandra, who with his oath of truth worked as a keeper of the cremation ground.

Influenced largely by the Marathas, this advertising campaign aimed at restoring Varanasi to its original glory during their rule. Holkar was direct in her restoration efforts, which included Manikarnika Ghat, showcasing the intersection of piety and architectural innovation.

Culturally, the ghats are melting pots of traditions. Classes in classical music and dance have been staged there from time to time. Great festivals like Ganga Mahotsav cherish the artistic heritage of Varanasi here. The ghats have served as rendezvous places for poets, philosophers, and scholars in the exchange of ideas, thereby further establishing their place in the intellectual and spiritual realms.

The Role of Ghats in Everyday Life

The ghats of Varanasi have a particular worldview of existence and death, dealing with great variety in action from dawn to dusk in every breath of existence.

At dawn, the ghats are already ablaze with activity, witnesses to scenes where devotees perform ablutions, yoga, and meditation. As priests conduct their rituals, pilgrims immerse themselves in the holy waters for the cleansing of the spirit. The boatmen take tourists across the river, offering them an unparalleled view of the ghats against the brilliance of the rising sun.

During the day, the ghats become a melting pot of sacred and spiritual activities. Vendors sell flowers, incense, and religious articles, while creative artisans do their best to sketch the ageless beauty of the riverfront. Sadhus or ascetics meditate on the bank of the river as stubborn embodiments of the renunciation of worldly desire.

The ghats also serve as the focal points for some of life’s most poignant rituals. Firewood continuously burns at Manikarnika and Harishchandra Ghats where families perform last rites for their loved ones. The comingling of life-affirming, death-invoking explicate rites zeal against the Hindu philosophy of the cyclical culture.

As night descends on the ghats, the Ganga Aarti becomes a veritable spectacle of devotion. Clad in saffron robes, the priests perform synchronized rituals with lamps, conch shells, and chants, weaving an ethereal tapestry of sublime sensations. Each night, this ceremony pays homage to the sanctity of the Ganges and reiterates its standing as the lifeline of millions.

Environmental Challenges and Conservation Efforts

While these ghats are a sight to behold, they have been confronted with drastic alterations from environmental pollution and urban encroachment. Industrial waste, sewage, and other excesses of human activity have adversely touched the actual Ganga, which feeds these ghats. As such, the acclaim gained by Varanasi as a travellers’ haven has already pushed it to the very verge when speaking of infrastructural sustainability.

With this has come the increased flow of conservation and restoration efforts aimed at the ghats in recent years. The Namami Gange program of the government brings in a project aimed at cleaning the Ganges and replenishing her; the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor Project has further enhanced ghats both in accessibility and aesthetics whilst still retaining their heritage.

Various local organizations and environmental activists work together to emphasize the need for sustainable practices such as littering, pollution, etc. to preserve the ghats for generations to come.

Conclusion

The ghats of Varanasi are not mere structures; rather, they constitute the living soul of the city. They are carved by history, myth, and culture, the testimony to the lasting companionship shared between mankind and divinity, and for centuries have served to remind one to think, renew, and reconcile oneself with the eternal truths of life and death.

Nourished by divine nostalgia, ghats remain, through thick and thin, an eleventh-hour inspiration. They are a sacred lineage that recurs into the bonds shared through generations. These spaces bring strength in faith, courage to confront challenges, and unity between diverse streams and stories of history. Here, each soul is granted serenity and consolation amidst joys and sorrows together with their ups and downs.