The Age of Exploration: How Maps Transformed the World

~Vani Mishra

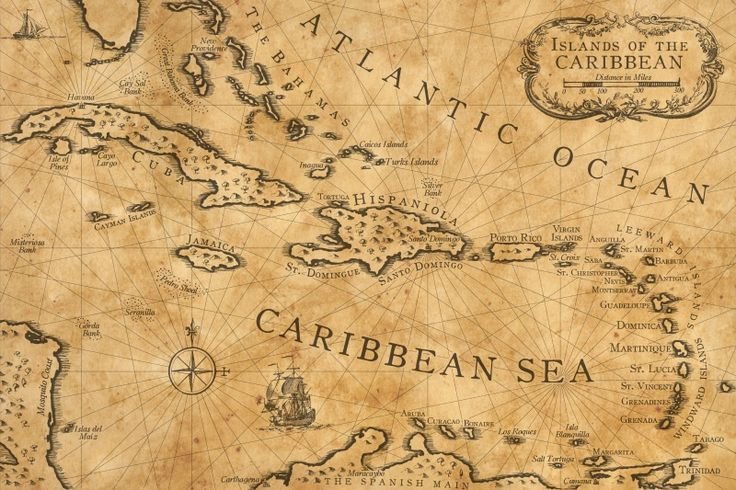

There was a time when the boundaries of the known world were sketched not in sharp lines but in speculation, fantasy, and sometimes in advisories: “Here be dragons.” Maps were more than travel guides for centuries. They were reflections of human desire, ambition, and fear. In the Age of Exploration, approximately between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, maps became instruments that transformed how people conceived of the earth and of themselves.

Retrospectively, it is astonishing that a mere sheet of parchment or paper, inscribed with ink, was able to change the destiny of empires and the course of history. It did. Maps assumed the unobtrusive presence of sailors who navigated unknown seas, the riches of kings who planned for expansion, and the signs of an era that did not hesitate to redefine the world’s borders.

Before the Voyages: Imagined Worlds

Maps were more about imagination and faith than accuracy for most of the Middle Ages in Europe. The well-known mappa mundi centered on Jerusalem, with Asia, Africa, and Europe spread out more symbolically rather than geographically. Maps were storytelling they represented a world view influenced by religion, myth, and inherited wisdom from classical authors.

But even in their inaccuracies, these maps show something deeply human. Humans wanted to understand the great unknown. They needed to visualize their position in the universe, even if the facts were incorrect. What they needed was not accuracy but meaning.

That started to shift in the fifteenth century, when technical improvements in navigation, mathematics, and printing began to turn cartography into something more scientific.

The Age of Discovery and the Wider Canvas

When the Portuguese mariners started hugging the coast of Africa, and when Columbus sailed west across the Atlantic in 1492, the old maps simply could not keep pace. Every new expedition required new portrayals of coastlines, rivers, and seas. The world was gradually being redrawn—not in fantasy but in experience.

The printing press was the key. Maps could now be mass-produced and disseminated. What had potentially been a lone valuable manuscript in a monastery library could now be printed and taken to merchants, explorers, and monarchs. Information was on the move, and with it, greed.

Imagine the authority of those early minutes: a sailor grasping a chart that identified the rim of Africa, a merchant unrolling a map that indicated a route to Asia, a monarch staring at a world that seemed to be expanding with each stroke on the page. The promise of potential was exhilarating.

Maps as Instruments of Power

Maps were never politically neutral. They bore the ambitions of those who had them drawn up. Once European empires started to expand outside their continents, maps became weapons of conquest and domination. A newly found territory was rapidly drawn, given a name, and claimed, usually with scant attention to the residents already there.

Cartography was a language of power. To place a line on a map was to claim ownership. Colonies were not merely conquered with ships and troops but also with charts and atlases. To Europeans, the map was evidence of possession. To indigenous peoples, it often was evidence of displacement.

At the same time, maps were badges of pride. Rulers kept showy world maps in their courts, not only as navigational instruments but as spoils of exploration. They were as much art as science, adorned with sea monsters, compass roses, and pictures of faraway peoples and strange animals.

A New Way of Seeing the World

The impact of these maps went beyond empire. They changed the way ordinary people imagined the earth. For the first time, one could see the continents drawn together in a single frame. Oceans that once seemed endless became measurable. The globe, which had been an abstract idea since antiquity, was now something tangible.

This change of mind was fundamental. Maps prompted people to think on a global scale, to realize that far-off places were linked, that commerce, conflict, and culture extended far past the horizon. They prompted curiosity. They inspired travel. They made the world, in a way, smaller and more comprehensible.

And yet, despite their increasing accuracy, maps were still profoundly human documents. They were full of errors, prejudices, and conjectures. Coastlines were distorted, islands misplaced, and areas inflated or reduced. But that, too, is part of their tale: maps show not only the world as it existed, but the world as folk thought of it.

The Legacy of the Age of Exploration

Now, when we unfold a map on a telephone or have satellites mapping out our location with pinpoint accuracy, we take for granted the magic that older maps had. But during their time, those hand-drawn maps were groundbreaking. They provided the link between imagination and reality, the known and the unknown.

They also remind us of the two sides of human progress. Maps facilitated connecting cultures, expanding knowledge, and spurring discovery. They were also used to justify conquest, erase identity, and carve up lands with borders that continue to spark war today.

Maybe that is why map history remains so compelling. They are not geography’s mere records. They are records of human aspiration our desire to travel, to conquer, to comprehend, and to belong.

The World on Paper

The Age of Exploration was a time of bravery, aspiration, and occasionally brutality. At its center were maps tissue-thin leaves of parchment that bore whole worlds on their surfaces. They were navigators for seamen, instruments of empire-building for nations, and portals for visionaries.

To view those ancient maps today is to see both the confines and the genius of the human intellect. They remind us that history is not a matter of battles and voyages alone, but of the subtle, painstaking labour of those who placed lines on a page, and in so doing, remapped the world’s horizons.