The Silk Route: Bridging Civilizations and Cultures Across Millennia

Silk Route or the Silk Road is one of the grand trading routes in the history of mankind. It crossed mountain ranges, desert sands, and thirteen thousand miles, connecting the East and the West for several centuries and shaping the cultures, economies, and civilizations along its path. It goes back in time to very ancient days when distant peoples became increasingly interactive due to the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies. The story of the Silk Route is not merely a story of trade but one of culture, political ambition, and human endurance.

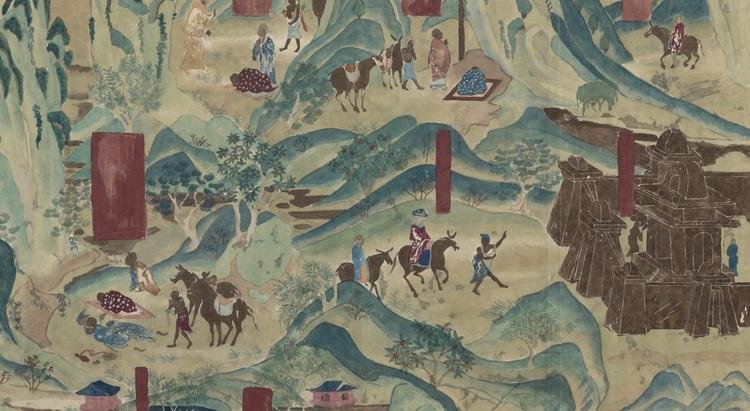

The term ‘Silk Road’ was coined by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in the nineteenth century for describing the lucrative trade in silk originating in China. Silk became one of the rarest and choicest of goods owing to its superior texture and went on to become a much-coveted item in the West. But much more was not traded across this route than just silk. It included precious metals, spices, textiles, glassware, and ceramics, much more than culture, including art, religion, language, and scientific knowledge. The Silk Route takes its origin in the Han Dynasty, wherein the systemic trade of the Silk Road founded by the Chinese ruling dynasty had been set up in the 2nd century BCE. The establishment of routes into the west continued as the Han Court tried to ensure an allegiance with tribes in Central Asia so as to strengthen their empire against invaders from northern areas. Chinese explorer Zhang Qian lent efforts to spearhead early engagements into these opened routes. Missions to Central Asian territories resulted in the introduction of different cultures and goods into China, causing a further flourishing trade to follow. Indeed, the Silk Route is not one route; instead, it consists of a complex web of connected paths. It traverses mountain ranges, steppes, and deserts, from big cities like Xi’an through Samarkand, from Baghdad to Constantinople. The road was long but full of difficulties: the severe weather, dangerous terrain, plus the always lurking danger of being robbed made it hard. Goods were moved across these desolate terrains by caravans of camels and horses, under the see of expert traders and navigators that had in-depth knowledge about the routes.

Beyond economic factors, the route worked to facilitate the movement of ideas and beliefs. For instance, Buddhism expanded from India to Central Asia and China through the Silk Route, where it changed the religious landscape. Other technologies, like papermaking and printing, came westward to affect the Middle East and Europe. Of course, in return, glassmaking, metallurgy, and other such Western inventions would find their way to enhance Eastern cultures. It is in such an exchange that ideas have propagated advancement in human life. The fortunes of the Silk Route were closely tied to the rise and fall of empires. On the one hand, the imperial demand for luxury by the Romans, as well as the calm that was brought about by the Pax Romana allowed merchants to trade safely. On the other hand, prosperity along the Silk Route was similarly a product of the promotion of commerce and culture during the Tang Dynasty of China and the Byzantine Empire. The dislocation caused by other forms of political discontent, such as the dissolution of the Roman Empire or the breakdown of the Abbasid Caliphate, was felt through the coming and going of goods and ideas. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Silk Route reached its highest development during the Mongol Empire. Genghis Khan and his successors established fare completions into an unprecedented period of height and security over most of Eurasia. Much of commerce and cultural exchange traveled along the route in this time of relative peace known as the Pax Mongolica. Marco Polo, the Venetian merchant and explorer, made the famous journey along that line while chronicling his adventures for an otherwise ignorant Europe. The Silk Route was beyond decline. With the 15th century, the bloom shifted away from its great and glorious past into maritime trade, catching the winds of expedient navigation and shipbuilding. Such innovations made it much easier for anyone who wanted to draw merits from overland trade to discover sea routes to India and China. In addition, with the creation of new political entities leading to a politically broken mesh, such as the Ottoman Empire, further hurdles developed within the network. By the 17th century, the Silk Route had been largely obstructed, but it still remembered.

This heritage of the Silk Route speaks volumes and is extremely varied. It transfers cultures and societies, from where people receive shares and recognition to create onto friendship through education and art. The combined East-West influences can be seen in architecture, literature, cuisine, and music. It signifies the immense power inherited by connectivity, showing that goods and ideas, when exchanged, can accelerate progress and innovation. In present-day history, the Silk Route has become the subject of much interest to historians, tourists, and politicians. Its revival has already begun in segments such as Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, which is projected to enhance connectivity across Asia, Europe, and Africa. All that remains of modernity in today’s projects are those which were once part of the ancient Silk Road-bridges that link up to civilizations, stressing out the endurance of cooperation and exchange as needed. The further history of the Silk Route glorifies and lauds human wit and ingenuity in adapting to environments. It underscores the interconnectedness of our world and our shared heritage. It reminds one of the ever-potent dialogue, exchange, and mutual understanding that determine the destinies of civilizations, as one recalls this extraordinary chapter of history.