MOHENJODARO: The earliest urban metropolis with a mysterious decline

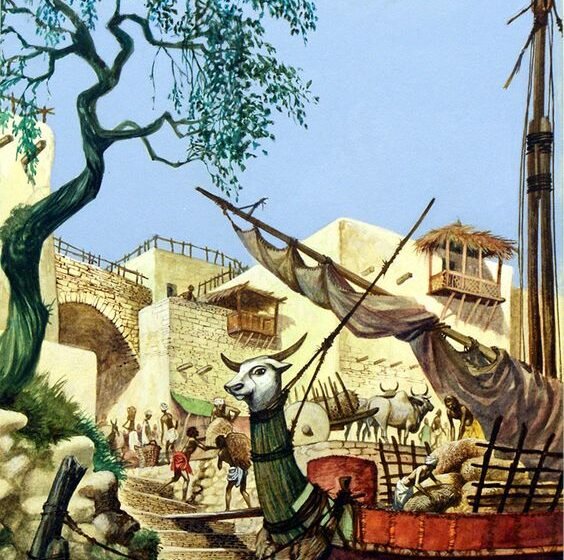

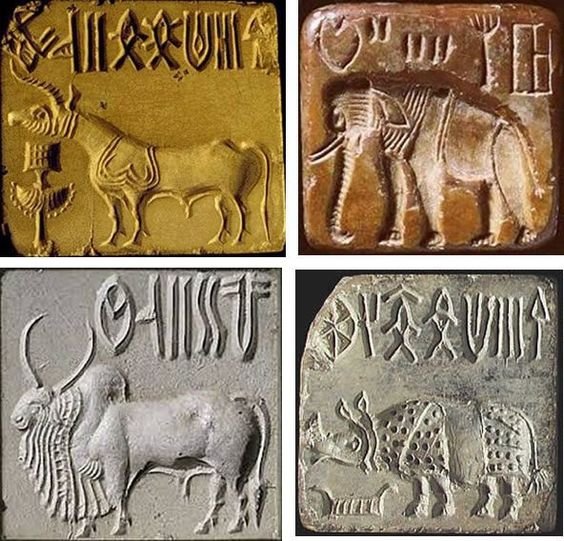

The second oldest human civilization in the world, discovered at the turn of the early nineteenth century, marked one of the biggest findings of an exceptional human settlement ever recorded in world or Indian history. India’s most ancient and sophisticated civilised culture prevailed in the Indus Valley from 2600-1900 BC. However, some recent studies suggest that the civilisation came into being as early as 3,300 BC indicating that it developed prior to the Egyptian civilisation and thrived as a contemporary to the Mesopotamian civilisation through prosperous trade links. There is a striking similarity found in the seals of Indus valley and those found in Mesopotamia. And it is also likely that the descendants of the Sumer dynasty of Mesopotamia may have entered the Sindh region.

Also known by the name of Harappan Valley Civilisation, it flourished in the bronze age as a remarkable urban settlement exemplifying modern day architectural features in symmetry and well channelled drainage system. The existence of this civilisation unravelled when the cities of Harappa and Mohenjodaro were excavated and information was gathered about the Indus civilisation through the ‘Archaeological Survey of India’ agency which conducted research on the ‘Indian cities during the time of the Aryans’.

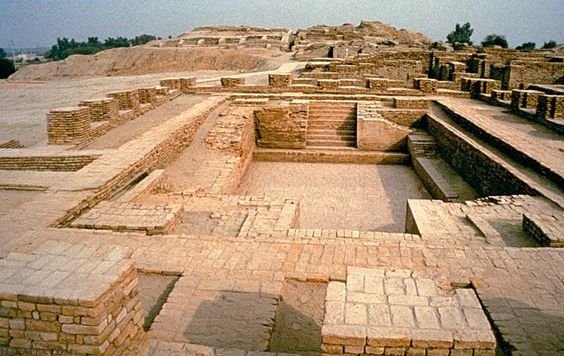

Designated as a Unesco World Heritage site in 1980, Mohenjodaro or the ‘Mound of the dead’ with other spelling variations such as Mohanjo-daro (Mound of Mohan =Krishna), Moenjo-daro or even Mohen-jo-daro, is reputed to be one of the earliest urban cities of South Asia situated on the right bank of the Indus River in the modern day Larkana district of Sindh province of southern Pakistan.

The hope of Harappa that drove the excavation

Motivated by the findings at Harappa, archeologists under the aegis of Sir John Hubert Marshall (English director general of the Indian Archaeological Survey (1902–31)), geared the excavation work at a location 400 miles from Harappa to unearth the city of Mohenjo-daro. So in the year 1921, Raibahadur Dayaram Sahani spearheaded the excavations at Harappa and gathered antiquities of the Indus Valley Civilisation while Rakhaldas Banerji excavated and discovered the ruins of Mohenjodaro in 1922. On the same lines, Nani Gopal Majumdar is known to have discovered another relatively small buried town named ‘Chanhu-daro’.

Major archaeological work at the Mohenjo-daro site was conducted through the 1930s under various directors, including K.N. Dikshit and Ernest Mackay. Although their methods were not as systematic as those used today such as the stratigraphic approach, their excavations yielded a wealth of data still valuable to researchers. Following Dr. G. F. Dales’ last significant dig in 1964-65, further large-scale excavations were halted to protect the site from environmental damage.

Since then, only limited salvage excavations, surveys, and conservation efforts have been permitted, mostly by Pakistani professionals. More recently, UNESCO, in partnership with the Department of Archaeology and Museums in Pakistan and international advisors, has focused on conserving the site’s remaining structures.

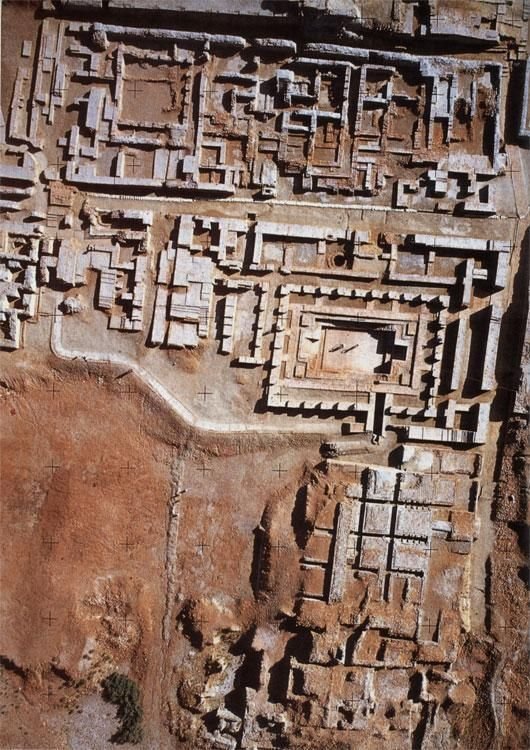

The excavations revealed Mohenjodaro as the largest urban centre of Indus Valley Civilisation once spread over a circuit of 5 km, and its rich components and structures as reminiscent of a capital of an extensive state.

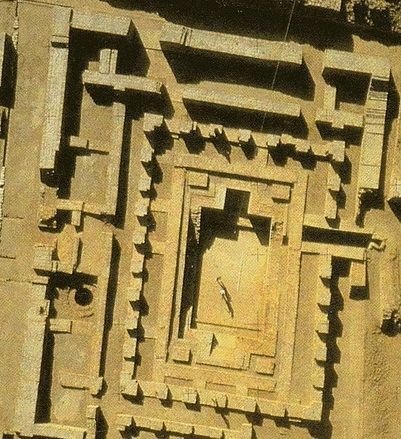

Mohenjo-Daro was divided into two sections, much like its contemporary cities, Kalibangan and Harappa. The higher western section, the Citadel, housed administrative buildings such as The Great Bath, granaries, and a presumed religious or educational centre, ‘the College of Priests’, on an elevated mud-brick foundation, surrounded by a substantial wall. The Lower town was home to the majority of the population, featuring a labyrinth of streets and lanes which was also fortified. This residential area was organised by occupational groups and yielded an abundance of everyday items and data on burial customs.

ARCHITECTURE

Town Planning

The most striking feature of town planning was the roads. In contrast to the Harappan roads that were strategically designed in a grid pattern orientation, Mohenjo-Daro, despite its size and importance, does not exhibit a perfect grid layout. Although the cities were meticulously planned, the roads were not always straight nor did they consistently intersect at right angles. At some junctures, these straight roads are curved and sometimes designed in east-west and north-south directions, on the whole, keeping in mind the direction of wind. The lower city’s roads divided it into four blocks, constructed from mud bricks and linked by smaller roads and alleys. The main road was wide enough to allow two bullock carts to pass side by side! The city was divided into big markets where the main roads seem to have been built stronger

by spreading a layer of brick pieces on the top.

As far as building structures are concerned, partly or fully baked bricks were used that were of standard proportion. The shapes of the bricks used for houses differed from those used for public roads and gutters. The walls were plastered with gypsum-mixed mud. Houses were generally simple in design, with the tops of the walls adorned with intricate brick patterns. The structures were either single or multi-story with flat roofs and railings around the edges. Each household had its own toilet, bathroom, a small kitchen in one corner and staircases made of either brick or wood. Provisions were made for rainwater drainage, and while houses had few windows, there was often one overlooking the courtyard. All house entrances faced lanes leading to the main road.

A meticulously planned drainage system

A notable feature of town planning was the advanced water supply and drainage system. Each household had at least one bathroom located by the street, with waste water directed through small gutters which were connected to a larger main gutter (nullahs), all covered with bricks or stones. The implementation of such a hygiene-conscious waste disposal system highlights the remarkable town planning and masonry skills of this ancient culture. Since these covered drains required regular cleaning, the lids were intentionally made from limestone, which is lighter compared to other rocks. Additionally, the Harappans used bitumen in these drains, representing one of the earliest known instances of waterproofing in history.

THE GREAT BATH

Regarded as the most spectacular marvel of the Indus Valley architecture, this rectangular public bath is situated in the citadel complex, constructed from fully kilned, durable bricks which measure 11.70 metres in length, 6.90 metres in width, and 2.40 metres in depth. The bath is situated 8 feet (2.5 metres) below the surrounding pavement. Its floor is made up of two layers of sawed brick plastered with gypsum-mixed lime, with a layer of bitumen sealer between them. Water was likely supplied by a large well located in a nearby room, and an outlet in one corner of the bath led to a high, corbeled drain that discharged water on the west side of the mound. Access to the bath was provided by flights of steps at either end, which were originally finished with timber treads set in bitumen.

Towards the north of this bathing structure, there are eight small bathrooms with a wastewater discharge system. The layout ensures that bathers do not face each other, even though the rooms are opposite each other. A well to the southeast supplied the water, and there was a special system for removing waste water and providing fresh water. The existence of such a public bath with separate rooms indicates the importance of bathing in Indus Valley culture. Since every house had a bathroom, “The Great Bath” was most preferably used for religious or festive occasions.

A hub of wells

A total of 700 wells were found in Mohenjodaro as against Harappa and Dholavira where a handful of them existed which indicates that people inhabiting this city relied on private and public wells for their needs despite being located near the Indus river. The rainwater collection drains were separate from the sewage drains. It is estimated that nearly every household in Mohenjo-Daro had its own private well, and the Great Bath was also supplied with water from one of these wells.

SCULPTURE CRAFTSMANSHIP

The people living in Indus Valley had a knack and skill for sculptural artefacts which include metal idols, terracotta sculptures, stone carvings etc. found here. Researchers have excavated 11 sculptures carved out of stones.

The Priest King

Representing one of the earliest attempts at sculpture , the ‘Priest King’ is particularly well-known. This soapstone artefact, found at Mohenjo-daro, stands 17.5 cm tall. The priest’s beard and moustache are intricately engraved, and his half-open eyes suggest a meditative state akin to a yogi. He wears a headband with a circular medallion in the centre of his narrow forehead. The priest dons a shawl decorated with trefoil knot patterns, painted red inside which used in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Crete, might have influenced the Indus Valley. This artefact is displayed at Karachi’s National Museum of Pakistan.

The Dancing Girl

Among the bronze sculptures which were made using the Lost-Wax technique, one notable find is the Dancing Girl (10.8 cm in height), a sculpture of a girl with arms extended to her knees and a pouty face, considered advanced for its time. British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler praised it, calling the girl “perfectly confident of herself and the world,” extremely rare in the world. It is displayed in the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Museum in Mumbai.

The ‘Seated Male Sculpture,’ carved from alabaster, is a significant stone artefact. The figure is cloaked in a petticoat-like garment wrapped around the waist and extending under the right hand, with the left hand resting on a slightly raised knee. The headless sculpture has an unfinished appearance, with a rough hair mass at the back and a rope-like feature that could be a hair braid or ornament.

Terracotta Sculptures

Terracotta figures of humans and animals were common in the Indus civilization. A notable terracotta human statue with distinctive features like a long nose and beardless face was discovered during the 1950 excavation of Mohenjo-daro’s grain house. Horned animal figures, possibly representing deities, were also found. Many terracotta statues of women, likely depicting goddesses or ancestral deities, were used in worship. One unique statue shows a woman in a low-waist dress with a fan-shaped crown used as oil lamps. Some female figures symbolise fertility, while others depict daily activities.

Seals (Mudra)

Seals from the Indus Valley, crafted from chalkstone, alabaster, and limestone, showcase fine art and craftsmanship. Over 1,200 seals, mostly square or rectangular, have been found at Mohenjo-daro, featuring engraved animal figures and hieroglyphics. Circular and cylindrical seals with thread holes were also common. These seals were intricately carved using saws, chisels, augers, and burins, then treated with alkali and kiln-fired for a shiny finish. The animal depictions, especially of bulls, are lifelike and comparable to Egyptian and Mesopotamian art.

Toys

Indus Valley toys, made from clay, shells, and ivory, reflect the artisans’ creativity, including miniature vehicles and movable bull figures, with mechanisms allowing the head to move via a thread.

An ornamental fondness

The inhabitants relished wearing ornaments made from precious stones and metals like Lapis Lazuli which were imported from Afghanistan, while gold and silver were sourced from Rajasthan’s Khetri mines. Popular items included bangles, necklaces, and beads made from semi-precious stones like steatite and agate. A notable find is a seven-stranded necklace made of gold and semi-precious stones, highlighting the area’s exquisite jewellery craftsmanship.

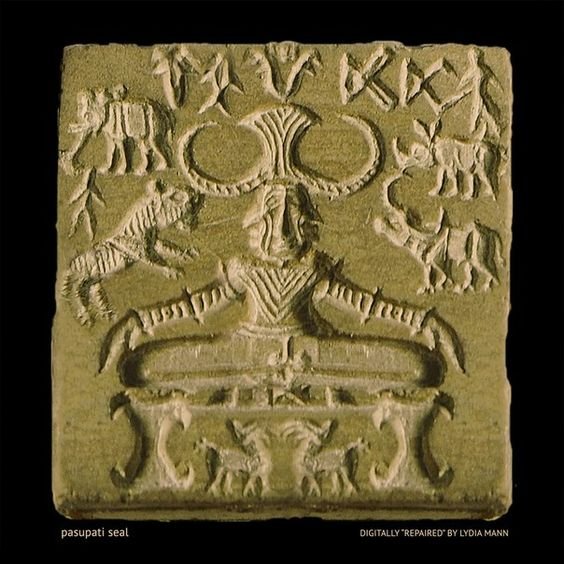

Whom did they worship?

Some later discoveries revealed that their society was matriarchal and the Mother Goddess, symbolising birth and fertility, was highly revered. Seals also depict Pashupati, or Proto-Shiva, a male figure resembling the modern Shiva, characterised by a visible phallus and a yogic posture, indicating his significance in society. While some also regarded him as a protector of tribes due to being surrounded by various animals.

AN INDECIPHERABLE DECLINE

Although various theories ranging from an Aryan invasion, climate change induced flood, a massacre and many more have been ascertained by some scholars, the exact reason for the series of circumstances that resulted in the decline of one of the most vibrant and prosperous civilizations still remains unknown. Few skeletons were found in the lower town which led some historians to come up with the theory of an external invasion. However, the undeciphered hieroglyphs might hide some answers.