Rediscovering Pachisi: The Timeless Indian Board Game that Inspired Parcheesi

Pachisi is a cross and circle Indian board game that is played between two to four people. Traditionally it is played on a cross shaped cloth, however, any surface may be used, including a drawing or engraving on the floor. The name of the game finds its roots in the Hindi word “Pacchis” meaning twenty-five. It is based on the highest number one can get to by throwing the cowrie shells. It is described as “Pasha” in the Mahabharata.

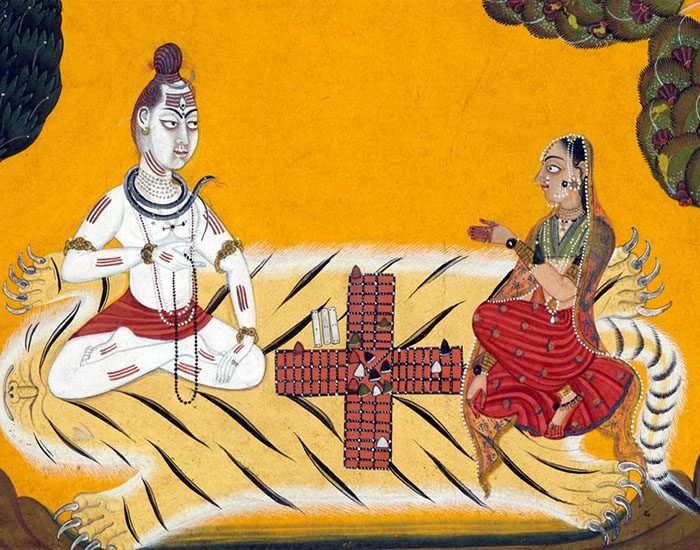

Mythologically speaking, the game has been mentioned in Skanda Purana where the lord Shiva-Parvati play the game. It is an important part of Mahabharata in which a match of Pasha takes place between Yudhishthira and Duryodhana. Archeologically, gamesmen similar to Pachisi has been found from Iron Age digging sites during Painted Grey ware period from sites in Mathura and Noh (110-800B.C.). In between the 6th-7th century, remnants of game identical with Pachisi are found in the Ellora caves. A Chinese document mentions that Chinese game “Pinyin-Chupu” draws its reference from a game invented in western India and spread to China in the time of Wei Dynasty.

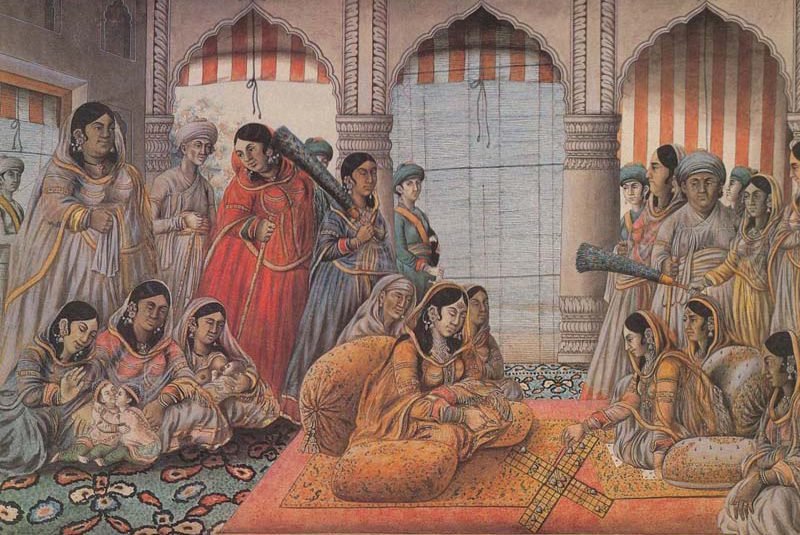

Some of the oldest evidences of the Pachisi is the Mughal- built Pachisi courts at Fatehpur Sikri and Agra, which date back to 16th century. Here the Mughal emperor Akbar and his noblemen would play the game at grand scale, not with Cowries, with courtesans taking the role of tokens in colourful costumes. This has been recorded in details by his biographer, Abul Fazl in great details. He mentions that game was very popular at the time, implying that Pachisi substantially pre-dated Mughal era. Many Mughal and Rajput paintings and manuscripts depict people playing this game.

Most cross and circle games employ a board with a circle encircling a cross, which is commonly in the shape of paths. This can also imply that the tokens used by players move in a circular pattern along the central cross without the presence of an actual circle, as in Pachisi. Pachisi’s board consists of four routes, each eight tiles long and three tiles wide. All four paths intersect in the middle region known as charkoni. Some tiles, often three or four per arm of the cross, are marked with a “X” and referred to as castles. They are arranged so that there is always a twenty-five-pace distance between the first castle on one arm and the last castle on the other arm, hence the term Pachisi.

In conventional games, four players were divided into two-person teams, with players seated across from one another on the same team. Each player received four tokens, which were all placed in the charkoni. The players took turns casting the cowrie shells, with the one with the highest roll making the opening move of the game, followed by the other in a counterclockwise pattern. Once the game began, each player moved one of their tokens based on the roll of the cowrie shells, first down the middle column of the arm facing the player, then up and down the outer paths of each of the remaining arms in a counterclockwise progression, with the last path being the same as the first. The first team to return all of its tokens to the charkoni after making a full circuit around the board won the game.

Capturing and blocking tokens was also an important aspect of the games. A player who landed on the same square as an opponent’s token was regarded to have captured it. Captured tokens were returned to the charkoni, who had to start the game over. In some versions of the game, a token could only reach the charkoni if it had captured at least one opponent token during its stay on the board.

Ludo, a late nineteenth-century British game, and Mensch ärgere Dich nich, an early twentieth-century German game, are two examples of early European adaptations of Pachisi. The game was later adapted into two American games: Sorry! and Parcheesi.

Today, Ludo is the most commonly played version of Pachisi in India, although the original version is still played in some parts. The ancient game has entertained families for millennia. From emperors playing a life-sized game to kids gathering around and playing on a bed, the journey of Pachisi illustrates the enduring power of shared experience. Roll the dice, accept a little bit of the past, and experience the magic of this ageless game.