Pāṇini: The Architect of Sanskrit and Descriptive Linguistics in Ancient India

In the intricate tapestry of ancient Indian scholarship, Pāṇini is celebrated as a legendary figure, revered for his profound contributions to linguistics. Hailed as the father of Sanskrit and linguistics, he emerges from the mist of ancient India, mentioned in fables and texts, with even the Panchatantra weaving tales of his demise at the jaws of a lion. Pāṇini, a Sanskrit grammarian, formulated a thorough and scientific framework encompassing phonetics, phonology, and morphology. Sanskrit, the classical literary language of the Indian Hindus, owes its structure and literature to Pāṇini, who is often hailed as its progenitor.

Pāṇini’s legacy, cloaked in a temporal enigma, continues to captivate scholars and linguists worldwide. As we embark on a journey through the life and works of this remarkable linguist, we unravel the threads of Pāṇini’s unparalleled influence on the study of language.

Origins of the Linguist:

Pāṇini’s personal life remains shrouded in uncertainty, with no definitive information available. An inscription from Siladitya VII of Valabhi refers to him as Śalāturiya, signifying a “man from Salatura.” This suggests that Pāṇini resided in Salatura, located in ancient Gandhara, which corresponds to present-day north-west Pakistan. Salatura is believed to be in proximity to Lahore, a town situated at the confluence of the Indus and Kabul rivers. Pāṇini’s birth places him in the epicentre of ancient Indian wisdom, with timelines oscillating between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE. This temporal ambiguity adds a layer of mystery to the life of a scholar whose impact resonates through millennia.

The name Pāṇini is a patronymic, signifying “descendant of Paṇina.” According to Patanjali’s Mahābhāṣya, his full name was Dakṣiputra Pāṇini, implying that his mother’s name was Dakṣi.

Regarding the dating of Pāṇini’s life, there is no definite information about the era in which he lived, not even the specific century. Scholars have proposed varying timelines, suggesting dates from the seventh to the fourth century BCE. In a comprehensive review by George Cardona in 1997, he asserts that the available evidence strongly supports a dating no later than between 400 and 350 BCE, while earlier datings rely on interpretations and lack probative evidence.

Pāṇini’s Imprint on Literary and Linguistic Frontiers:

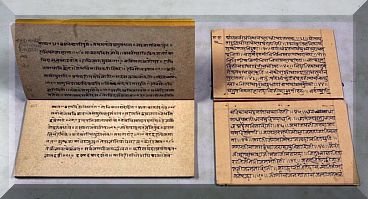

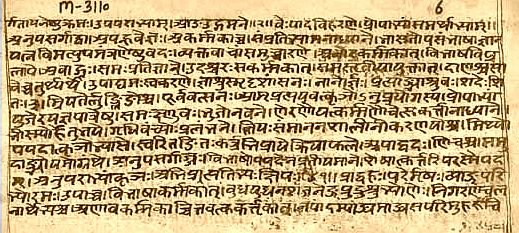

Pāṇini is renowned for the Aṣṭādhyāyī, a sutra-style treatise on Sanskrit grammar consisting of 3,996 verses or rules spread across “eight chapters.” This seminal work is considered the foundational text of the Vyākaraṇa branch of the Vedanga, the auxiliary scholarly disciplines of the Vedic period. The aphoristic nature of his text has attracted numerous commentaries, with Patanjali’s Mahābhāṣya standing out as the most famous among them. Notably, Pāṇini’s ideas exerted a profound influence and garnered commentaries from scholars across various Indian religions, including Buddhism.

Pāṇini’s analysis of noun compounds is another timeless milestone, as it continues to underpin contemporary linguistic theories of compounding in Indian languages. His comprehensive and scientific grammatical theory is conventionally recognized as marking the initiation of Classical Sanskrit, contributing significantly to the development of the language. This systematic treatise served as a source of inspiration, propelling Sanskrit to the forefront as the preeminent Indian language for learning and literature for a remarkable span of two millennia.

Pāṇini’s theory of morphological analysis was a groundbreaking achievement, which was notably more advanced than any equivalent Western theory preceding the 20th century. His treatise adopts a generative and descriptive approach, employing metalanguage and meta-rules. A fascinating comparison places Pāṇini’s work in the realm of a Turing machine, where the logical structure of any computing device is distilled to its essentials through an idealized mathematical model. This visionary aspect of his theory foreshadows concepts that would only find resonance in Western linguistic thought much later in the 20th century.

Sculpting Language: Aṣṭādhyāyī and Bhaṭṭikāvya by Pāṇini

The Aṣṭādhyāyī stands as the magnum opus of Pāṇini, representing the most significant among his various works. This grammar, which essentially defines the Sanskrit language, is modelled on the dialect and register of elite speakers in Pāṇini’s time while also incorporating features of the older Vedic language.

Functioning as a prescriptive and generative grammar, the Aṣṭādhyāyī employs algebraic rules that govern every facet of the Sanskrit language. Complemented by three ancillary texts—akṣarasamāmnāya, dhātupāṭha, and gaṇapāṭha—this comprehensive work reflects a meticulous effort to preserve the language of the Vedic hymns from corruption. It serves as the culmination of a centuries-long, sophisticated grammatical tradition devised to arrest language change.

The Aṣṭādhyāyī‘s preeminence is emphasized by its ability to eclipse all similar works that preceded it. While not the first of its kind, it holds the distinction of being the oldest surviving text of its kind in its entirety. Comprising 3,959 sūtras in eight chapters, each subdivided into four sections or pādas, the intricacies of its rules and metarules continue to be explored and deciphered by scholars even centuries after its composition.

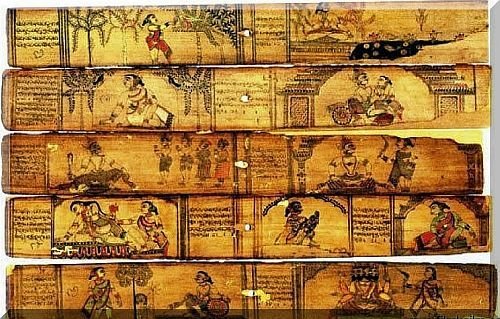

In an era dominated by oral composition and transmission norms, Pāṇini’s Aṣṭādhyāyī is deeply rooted in that oral tradition. To ensure wide dissemination, Pāṇini is believed to have favoured brevity over clarity, and the entire text can be recited end-to-end in two hours. Consequently, a multitude of commentaries has emerged over the centuries, predominantly adhering to the foundational principles laid down by Pāṇini’s work.

Bhaṭṭikāvya, another significant aspect of Pāṇini’s legacy, showcases the enduring influence of the Aṣṭādhyāyī. As an integral part of the Indian curriculum in late classical times, this poetic work by Bhaṭṭi serves as a study aid to Pāṇini’s text. By ingeniously weaving examples from existing grammatical commentaries into the context of the gripping and morally uplifting story of the Rāmāyaṇa, Bhaṭṭi breathes life into the otherwise dry bones of grammar. In his own words, this composition acts as a lamp for those who perceive the meaning of words and a hand mirror for those without grammar, embodying a joy for the sufficiently learned while perhaps slighting the dullard.

Pāṇini is credited with two other literary works, both of which, unfortunately, have been lost to time. One of these lost works is Jāmbavati Vijaya, referenced by Rajashekhara in Jalhana’s Sukti Muktāvalī. While the work itself is no longer extant, a fragment can be found in Ramayukta’s commentary on Namalinganushasana. From the title, it can be inferred that Jāmbavati Vijaya dealt with Krishna’s conquest of Jambavati in the underworld as his bride, as suggested by Rajashekhara in Jahlana’s Sukti Muktāvalī.

In addition to his literary contributions, Pāṇini’s influence extends to the realms of mathematics. Numerous mathematical works related to Pāṇini’s contributions exist. Pāṇini displayed a wealth of ideas in organizing the grammatical forms of his era systematically. In a manner akin to mathematicians who use mathematical language to model known phenomena, Pāṇini devised a metalanguage that closely aligns with modern-day algebraic concepts. His innovative approach to structuring grammatical forms echoes the principles of algebra, showcasing the enduring interdisciplinary nature of his contributions.

Pāṇini’s Resurgence in Modern Linguistics:

The 19th-century European stage witnessed the resurgence of Pāṇini’s work, influencing modern linguistics through luminaries like Franz Bopp. The echoes of Pāṇinian grammar reached Sanskrit scholars such as Ferdinand de Saussure, Leonard Bloomfield, and Roman Jakobson. The impact on formal language rules, proposed by Saussure and later developed by Chomsky, traces its origins to Pāṇini’s structured linguistic approach.

Ferdinand de Saussure, the father of modern structural linguistics, acknowledged Pāṇini’s influence on his foundational ideas. From the concept of semiology to the unity of signifier-signified, Saussure’s work bears the imprint of Pāṇini’s linguistic legacy. Leonard Bloomfield, the founding father of American structuralism, pays homage to Pāṇini in his 1927 paper, “On some rules of Pāṇini.” Bloomfield’s recognition of Pāṇini’s rules further solidifies the Indian scholar’s enduring influence on the evolution of linguistic thought.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, Pāṇini, the eminent Sanskrit grammarian, stands as a foundational figure whose influence resonates through linguistic, literary, and mathematical realms. His magnum opus, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, not only defined the Sanskrit language but also laid the groundwork for the classical tradition, making Sanskrit the preeminent language of learning and literature for centuries. Pāṇini’s innovative theories on phonetics, phonology, and morphology showcased a level of sophistication unparalleled in his time, fostering a comprehensive understanding of language structure. Beyond linguistics, his foray into mathematics and the creation of a metalanguage underscore his interdisciplinary contributions, drawing parallels with modern algebraic concepts. Pāṇini’s legacy endures not only in the intellectual corridors of linguistic studies but also in the broader landscape of literature and mathematics, making him an enduring beacon of ancient Indian scholarship.