Art with the mystical pen– Kalamkari of Andhra Pradesh

- Lifestyle Asian history Medieval history

Khadija Khan

Khadija Khan- January 17, 2023

- 0

- 441

The major source for the well-known textile art, one of the simplest forms of visual art and design, known as Kalamkari, is the Swarnamukhi River’s banks, which are close to Srikalahasti, Andhra Pradesh.

Indian handicraft artists have created aesthetic harmony on a variety of surfaces, including metal surfaces, terracotta, glass, and trees– practically all imaginable materials, to build diverse insights of tradition and culture. Since Kalamkari was first practised over three thousand years ago, there have been many trials and errors. “Kalam” refers to a pen used in painting, while “Kari” in Urdu alludes to the craftsmanship involved. It may be traced back to the early time of alliance during the commerce of Indian and Persian trade merchants who recognised these textile paintings. Through time and fashion, artists have consistently developed their craft of painting stories.

Artists in Srikalahasti, unlike other locations where this specific art is done, continue to use age-old dying methods that have been handed down through the centuries. Kalamkari most likely began with depicting religious rites in south India.

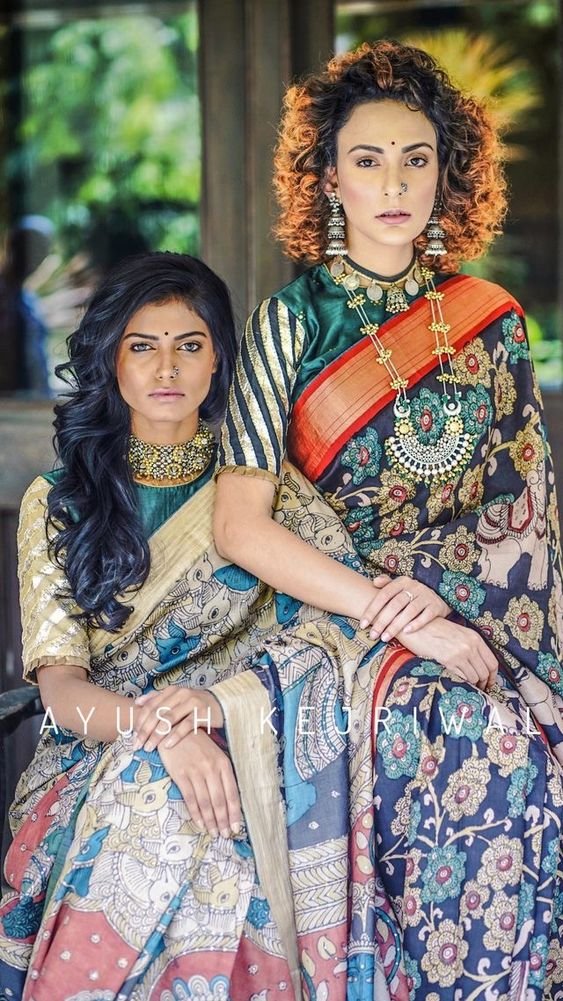

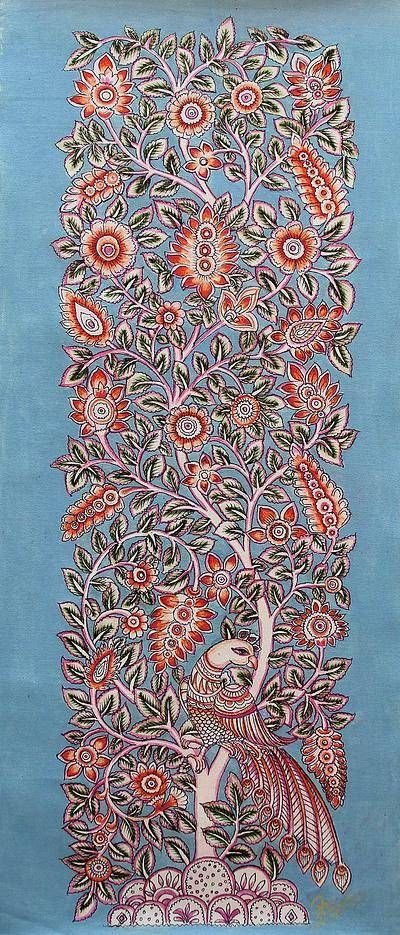

Folk singers used to travel around villages, telling the villagers tales from the Ramayana and Mahabharata during those times. Storytelling gradually changed into paintings, giving rise to a new art style known as Kalamkari. On kalamkari sarees, many motifs, like as flowers, peacocks, and paisleys, were frequently painted. Historical forts, temples, and architecture also served as basic inspiration. Currently, wall hangings, sarees, dupattas, and wall panels are also produced using this textile art style.

When painting, kalamkari artists are completely free to express themselves uniquely; unless specifically requested by a buyer, no two works are ever identical. The brilliant colours and lack of shading are what give kalamkari paintings their unique characteristics. Each piece is formed through intricate craftsmanship. In dupattas and sarees, several Hindu myths and scenarios are shown in succession.

Contrary to earlier times, when only cotton was used, kalamkari may be done on all kinds of fabrics, including silk, tussar, chiffon, and georgette. A basic patterned saree can take up to 20 days to make and is cleaned four times, making kalamkari a labour-intensive craft.

For kalamkari, the weather is very important because rainwater can ruin the fabric’s outlines while high temperatures can cause the colours to spread. It takes 23 to 25 stages to complete a kalamkari painting, including dying, bleaching, hand painting, tracing, washing, and ironing.

In brief, chanderi or cotton cloth is purchased and washed in plain water to remove any starch. Then it is dried, washed again and soaked in a solution of cow milk and chebulic myrobalan locally known as karakha pindhi for about 1 to 2 hours and eventually dried again. It is then ready for the basic outline drawing with a help of burnt tamarind stick that acts as charcoal/chalk piece. Once the basic outline is complete, black lines are drawn around the edges using a thin bamboo stick (Kalam). The inside is then hand-painted with a single colour using kalam, and once again rinsed in plain water. The material is placed in boiling water for the maroon/red colour to adhere to the fabric. Until all the colours are used, the washing procedure is repeated. After ironing, pressing, and proper packaging, the cloth is ready to be shipped.

Instruments

The Kalamkari pen is without a doubt the most important instrument used in Kalamkari painting, along with natural colours. Burnt tamarind sticks are also used to make the contours. When painting with kalamkari, a wooden frame called a “maggam” is used to hold the cloth on both ends.

Technique

- Dyeing Process

Although diverse sarees might take up to two to three months to complete and a simple one may be finished in ten days, many artists work on a single saree at a time. The more skilled artisans design the spaces within, while the less skilled ones draw the outline.

- Making brushes (Kalam)

The Kalamkari pen is comprised of a bamboo reed with a fabric coiled on one end that is sharpened. A cotton fabric is wrapped around the stick in a certain design, and a thread is wound around it to hold the cloth in place. When a cotton cloth, soaked in dye, is applied to the fabric, it serves as a filler. The pen must first be dipped in the necessary dye before being gently pressed to release the colour. In contrast to the pen used to fill in huge areas, the one used to draw the outlines is sharper.

- Organic Plant Dyes

There are about 500 plants that are discovered as a means to create natural colour, but just a few of them are abundant, affordable, and provide visually appealing colours. Some organic dyes used to create various hues are:

- Light yellow is created with karakha pindi (chebulic mayrabolan is combined with cow milk)

- Black fabric outlines made with kassim kaaram (Jaggery, rusted iron filings, and water).

- Blue is produced by natural indigo.

- Golden yellow is produced by pomegranates.

- Rosemary is created by Catechu (Suryadu chakka).

- Red is produced in Algeria.

- Water and alum together produce grey.

- Cow Milk (Highlights the fabric’s colour).

- Designing

Small tamarind sticks are burned before being coated in sand to allow them to cool naturally without becoming brittle. The sticks become worthless for sketching outlines on cloth if water is introduced to the fire. When sketched on cloth, burned Tamari sticks function as a graphite pencil. The contours are traced as artisans spread out the cloth and clip it at both ends to make it simpler for them to sketch. Since the outlines must be exquisite and exact, only skilled craftsmen are chosen. Learning to draw the outlines typically takes a trainee three months, while learning to fill the fabric with colour takes around fifteen days. Running designs are produced by skilled artisans freehand without the use of any references. The contours of the cloth are traditionally created with the burned tamarind sticks, although skilled craftsmen can also use a kalamkari pen to directly draw the outlines in black (kassim karam). Kassim cannot operate at extremely cold temperatures.

Since kassim spreads when exposed to high temperatures, kalamkari work is done in the early hours of the morning in the months of April and March. The artisan sketches the outline or pattern on the butter sheet or tracing paper, and small holes are drilled along the borders on the sheet. Tracing is typically done on unique client orders or on a particular god or goddess that craftsmen are unfamiliar with the design. Black powder is then applied around the edges of the tracing sheet while it is still on the cloth, creating an outline on the fabric below.

- Installation of Wooden Frame

After the fabric is fastened at one end, it is gently stretched to the other end and then locked and fixed in place with the help of a piece of local wood known as a karra. This wooden frame is called kalamkari maggam. If the craftsman needs the cloth to be more elastic later on, the wooden frame may be modified.

- Painting and Drawing

Inspiration for Kalamkari designs, motifs, and painting styles came from Indian palaces, monuments, and temples as well as from nature patterns. The cloth is spread out completely and once the outlines on the fabric have been made, the colouring and filling procedure begins. Up to 10 craftsmen work independently to add colour to various parts of a single fabric. Alum, which is essentially colourless but functions as a highlighter when painted and a natural mordant to make the colour adhere strongly to cloth, is combined with karaka pooh (maroon) to create a solution. The parts that will be filled in red or maroon are first painted, and they are then allowed to cure for one to two days in diffused sunshine so that the fabric can fully absorb the colour.

It is advisable to wash the cloth in flowing water to prevent the extra alum and colour from sticking to the opposite end of the fabric while washing it rhythmically to ensure that it is eliminated. After thoroughly drying in the sun, the cloth is boiled in water before being dried. The cloth is dried after being re-soaked in pure milk. When subsequent colours are put to the cloth, milk serves as wax to stop colour from bleeding. The cloth is then painted using brilliant colours such as blue, grey, yellow, and golden yellow on canvas using kalamkari pens. All colours employ alum since it has a mordant property. To remove extra colour, damp cloth is gently pushed against the coloured region.

Finally, the cloth is then rinsed in running water to eliminate impurities, soaked in lukewarm water to remove excess alum and colour, and ironed, ready to be delivered to the customers. Depending on the style and pattern, kalamkari painting on sarees might take up to 50 days to complete. Nowadays, trendy designs are highly popular, but every professional kalamkari artist has their own aesthetic and creative freedom to use a variety of designs and motifs.

The majority of traditional crafts, including Kalamkari, require a lot of labour and use materials difficult to acquire (handmade instruments, natural dyes) The advantage of kalamkari has always been its use of organic dyes, so it did not face competition from other textile centres throughout the world as such colours were scarce and their use was unproven. But the decline in Kalamkari began in the 19th century when the British brought low-cost aniline dyes that were popular among Indian craftspeople. Many kalamkari centres still perceive this as a true threat. Unfortunately, simple-to-use chemical dyes appeal to traditional artisans as their old process are labour intensive. For instance, a gorgeous red dye made from the roots of the manjishta plant is sometimes replaced by the artificial dye Alizarine. Similar to how German blue is frequently used in place of real indigo.

Comprehensive, exclusive, and protective law for the handloom weavers and their goods is now required in a nation like India– a country with a rich heritage and a strong handloom legacy. If it is implemented, traditional craftsmen and weavers will at least have a chance to safeguard their art and materials and compete in the market; otherwise, the existing textile industry would incline towards the end for this age-old legacy in the coming years.