Women in Athens and Sparta: Two Worlds, One Gender, Completely Different Lives

-Prachurya Ghosh

The Athenian Ideal: Silence, Seclusion, and Obedience

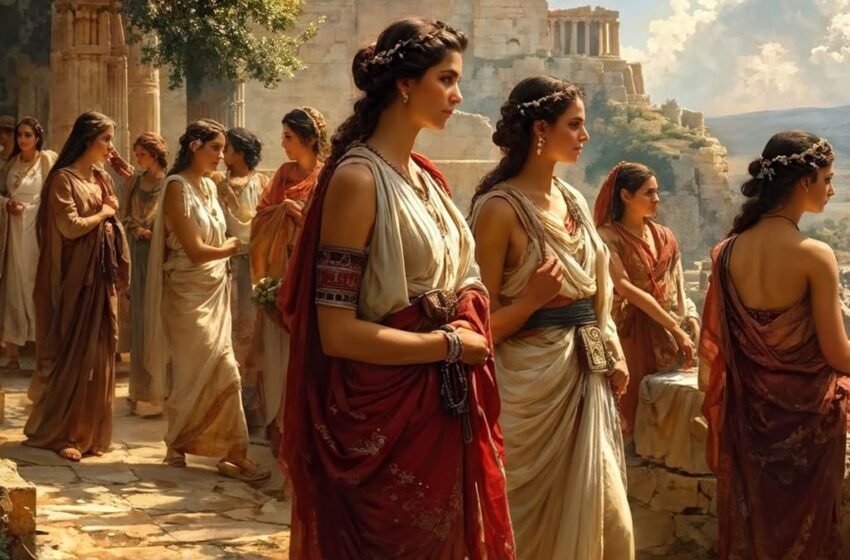

In Athens, a woman’s life was shaped almost entirely by the expectations of marriage and motherhood. From the moment she was born, an Athenian girl was trained to become a suitable wife, meaning someone who would obey her husband, manage the household, and ensure the continuation of the male family line. Her upbringing did not include intellectual or political education, as these were considered unnecessary and even dangerous for women. Instead, she was taught skills such as weaving, sewing, spinning, and basic household organization, all of which took place in the ginekonitis, a secluded part of the house reserved for women. This spatial separation symbolized a deeper ideological separation: men belonged to the public world of politics and debate, while women were confined to the private world of family and reproduction.

Although Athenian women were trained to perform domestic work, elite households relied heavily on slaves. As a result, the wife’s central role was not labor but legitimacy. Her primary duty was to produce lawful heirs, particularly sons who could inherit property and participate in civic life. Once a boy reached the age of seven, he was removed from the women’s quarters and educated by men, marking a clear break between maternal care and male socialization. Girls, however, remained under female supervision for life and rarely left the domestic sphere. Marriage itself often occurred at a very young age, usually arranged by male relatives, leaving women with little or no agency in choosing their partners.

Sexual Double Standards and the Status of Pallakides

Athenian society enforced a rigid sexual double standard that strongly favored men. While wives were expected to be sexually faithful and morally pure, men were socially permitted, and even expected, to seek pleasure outside marriage. Pallakides, or concubines, existed within a socially accepted category of women who could engage in sexual relationships with married men without social scandal. These women could live in the household, attend festivals, and even receive some education. In contrast, a “respectable” wife was expected to remain invisible, silent, and confined to the home.

This created a deeply paradoxical system in which socially marginal women had more freedom of movement and expression than legitimate wives. Respectability came at the cost of autonomy. The Athenian ideal of female virtue was thus built not on empowerment, but on control and exclusion from public life.

The Spartan Ideal: Strength, Voice, and Public Presence

In Sparta, women were shaped by an entirely different social logic. Spartan society was organized around warfare and survival, and every citizen, male or female, was expected to contribute to the strength of the state. For women, this meant physical fitness rather than domestic silence. Spartan girls received formal physical training from childhood, including running, wrestling, discus throwing, and endurance exercises. These activities were conducted in public and often alongside men, something unimaginable in Athens.

This physical training produced women who were confident, outspoken, and socially visible. Spartan women were not confined to the home and were encouraged to express opinions, debate, and influence decisions within the household. Although they could not formally participate in political institutions such as the assembly or the war council, their voices carried real social weight. A Spartan woman could openly criticize her husband, advise him on public matters, or shame him if he acted dishonorably.

Clothing, Body, and the Meaning of Freedom

The difference between Athenian and Spartan values was also reflected in clothing and attitudes toward the body. Athenian women wore long robes that covered most of their bodies and symbolized modesty and restraint. Spartan women wore short tunics that exposed their legs and allowed physical movement. To outsiders, this seemed scandalous and immoral, but within Sparta it was seen as natural and practical. The female body was not sexualized or hidden, but treated as a tool for producing strong citizens.

However, Spartan freedom must be understood carefully. While Spartan women enjoyed greater visibility and mobility, their freedom existed within a rigid ideological framework. They were free not for personal fulfillment, but for the biological and political needs of the state. Their bodies belonged, in a sense, to Sparta.

Marriage and Sexual Norms in Sparta

Marriage in Sparta differed significantly from Athens. While Athens normalized male infidelity, Spartan society emphasized monogamy and discouraged extramarital relationships. Marriage was not romantic but civic, aimed at producing future warriors. The ideal Spartan household consisted of one man and one woman, united by duty rather than emotional intimacy. Even sexual relations were viewed as functional rather than pleasurable, designed to maximize physical fitness and discipline.

Motherhood, Sacrifice, and State Loyalty

The most extreme aspect of Spartan ideology was its attitude toward children. Newborns were examined for physical fitness, and those deemed weak or disabled were often killed. This practice was justified as necessary for collective survival. Mothers were expected to accept this without emotional protest, demonstrating loyalty to the state over personal attachment.

This mentality is expressed in the famous phrase “ἢ τὰν ἢ ἐπὶ τᾶς” (“i tan i epi tas”), meaning “either with it or on it,” spoken by mothers as they handed their sons their shields. The message was uncompromising: return victorious or return dead. A son who survived as a coward was more shameful than a son who died bravely. Spartan motherhood was therefore not nurturing in the emotional sense, but ideological, disciplined, and militarized.

Two Models of Womanhood, Two Models of Society

The comparison between Athens and Sparta reveals two fundamentally different constructions of womanhood. Athenian women were controlled through isolation, silence, and moral regulation. Spartan women were controlled through discipline, physical training, and ideological loyalty. One system produced obedient wives who lived in domestic confinement. The other produced strong mothers whose primary emotional bond was not to family but to the state.

Both societies were deeply patriarchal, yet their mechanisms of control were distinct. Athens excluded women from public life in the name of respectability and social order. Sparta included women in public life in the name of military efficiency. In both cases, women existed not as independent individuals but as instruments of male-dominated political systems.

Ultimately, these contrasting models show that gender is not a universal or natural condition, but a social and political construction. What it meant to be a woman depended entirely on what the city-state required. In Athens, a woman was trained to disappear into the household. In Sparta, she was trained to endure and sacrifice for the state. Their shared biological sex masked profoundly different social realities, demonstrating that womanhood in ancient Greece was not one experience, but many shaped by power, ideology, and survival.