The Eradicate Sparrow Campaign: A Forgotten Chapter of the Great Chinese Famine

-Oishee Bose

On a normal evening in 1958, a town square was full of noise and faces. People carried pots and pans, children climbed trees to reach nests, and neighbours celebrated as eggs were shattered and fledgling were extracted from hiding spots. The energy of the time appeared to be that of a harvest festival. Local leaders lauded the job as did radio broadcasts. That scene played over town after town until the total impact was a drastic altering of the way whole terrains functioned rather than local ceremony. This is the tale of how a little, ordinary bird became the centre of a national policy that progressed from a slogan to mass action, how that activity interacted with other policies to aggravate a developing catastrophe, and how historians, ecologists, and economists have sought to assess the extent of what happened.

Origins and official logic

The Maoist regime in People’s Republic of China presented the Great Leap Forward as a national sprint. Leaders spoke about sudden transformation and set public targets that demanded visible results quickly. The Four Pests campaign began in 1958 as a clear, simple project that appealed to the same appetite for immediate achievement. The campaign named rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows as problems to be solved. Policymakers offered an arithmetic that was easy to explain and even easier to act upon: a widely circulated figure claimed a single sparrow ate roughly two kilograms of grain per year. That kind of number made the problem feel measurable and the solution feel obvious. People could be mobilized to act, and action felt patriotic because it promised more grain for the nation.

Local organization supplied the legs for this national idea. Party cadres, schoolteachers, factory groups, and neighbourhood committees received direct instructions to organize hunts, tally results, and celebrate success. Public life changed quickly as the communal rituals of noise and capture spread. Scientists and agronomists who tried to introduce caution, entered a political atmosphere that rewarded clarity and patriotic fervour and discouraged complex debate. The campaign moved from slogan to practice in a matter of months, and once practice began it developed momentum that proved very hard to stop.

How the campaign was carried out

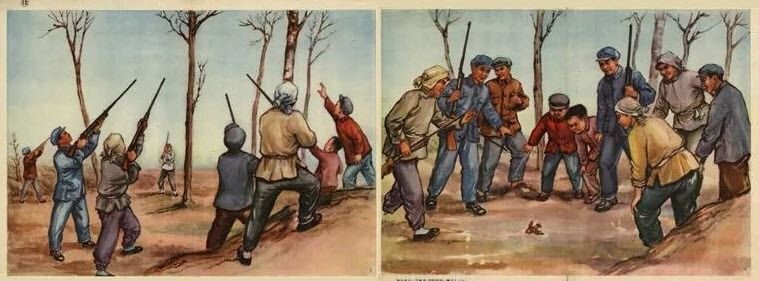

Practical methods were straightforward and visible. Groups beat pots and drums into the night so sparrows could not settle. Over-exerted birds sometimes dropped from exhaustion or became easy prey. Villagers climbed trees to pull down nests, smashed eggs, and captured adult birds with nets and slings. Children were enlisted as helpers and public events rewarded neighbourhoods that reported larger kill counts. Official statements and newspapers featured lists of numbers, and the intensity of public participation showed on the ground.

Exact totals of birds killed differ across accounts and scholars advise caution about precise figures. Several contemporaneous sources and later summaries place the toll in the hundreds of millions for a single year, and many accounts cite cumulative figures approaching two billion sparrows over the late 1950s. Historians emphasize that such large figures should be treated as estimates rather than exact head counts. The unavoidable historical point remains: sparrow populations crashed rapidly across broad areas because of concerted, nationwide actions that destroyed adults, eggs, and breeding sites.

Ecological role of sparrows in farm landscapes

Sparrows looked ordinary because their work happened quietly. Those birds ate both small amounts of seed and substantial numbers of insects. Parent sparrows fed many insect larvae to their chicks, and adults took locust nymphs, caterpillars, beetles, and other herbivores that damaged crops. Ecologists describe this as a trophic interaction. Removing a predator or insectivore reduces pressure on pests and allows those pests to multiply quickly, because many insects reproduce at fast rates.

Farmers sometimes noticed the consequences only after damage had begun: more caterpillars on millet, larger swarms of grasshoppers, sudden holes in otherwise healthy wheat heads. Removing sparrows therefore produced two effects at once. The little quantity of grain consumed by birds was lost directly, and a much larger, subtler service, which is the constant suppression of pest populations, also disappeared. Ecologists and later historians described removing a widespread insectivorous bird at scale as effectively firing a vast unpaid workforce of pest control. The consequences then unfolded faster than communities could adapt.

Interaction with other policy failures and the slide toward famine

A number of policy shifts in the late 1950s reduced rural resilience. Collective farming reorganized land use and local management. Production targets set by central authorities often proved unrealistic. State grain procurement took large portions from rural stocks to supply industry and cities, leaving villages with small buffers against shortfalls. Local officials faced powerful incentives to report high yields and to meet quotas set far above realistic output. Varied weather conditions in some regions compounded the political stresses.

The sparrow eradication entered as another shock layered on this fragile foundation. Comparative analyses that use county-level data and proxies for ecological suitability show that counties where sparrows had been common tended to experience larger percentage declines in yields after the campaign than counties less suited to sparrows. A prominent study that attempted to quantify the marginal effect of the anti-sparrow campaign calculated localized rice yield drops of roughly 5.3 percent and wheat declines of about 8.7 percent in sparrow-suitable counties relative to less suitable counties. That same paper interpreted its model outcomes as amounting to nearly 19.6 percent of the observed national decline in yields during the famine years, and it associated that marginal effect with approximately two million excess deaths across 1959–1961.

Historians who emphasize institutional responsibility push back against single-cause explanations. A large volume of scholarship locates primary responsibility for famine mortality in coercive policies, procurement rules, and incentive structures that led to massive misallocation of grain. Economists and ecologists treat sparrow removal as a measurable amplifier of those governance failures rather than as their root cause. Good historical practice treats the eradication program as a significant but not solitary contributor to the crisis. The combination of biological shock and policy failure magnified harm.

Concrete numbers and what they tell us

Numbers shape perception and policy. The commonly cited range for total excess deaths in 1959–1961 lies roughly between about 16.5 million and as many as 45 million people, with variation caused by different demographic methods and sources. Scholars who try to isolate the sparrow campaign’s role employ different datasets and econometric choices that produce different numerical outcomes. Contemporary sources and later summaries cite vast counts of dead sparrows and place cumulative kills in the hundreds of millions or near two billion. The figure of roughly two kilograms of grain per sparrow per year shows how an arithmetic framed the public debate and made action seem to follow directly from calculation. That arithmetic influenced popular perception and administrative action, helping to turn a small statistic into a large public movement.

Human stories and social memory

Numbers describe scale, but personal testimony provides texture. Oral accounts from survivors and village histories record a mixture of pride, confusion, and later regret. People often took part in the activities convinced they were protecting harvests and feeding families. Later they found themselves facing empty storehouses and loss. That shift created deep social grief and ruptured trust. Public discussion of famine and of the sparrow program’s contribution remained constrained for decades. Late twentieth-century and early twenty-first-century scholarship began to combine demographic reconstruction, archival research, and ecological analysis to fill out the memory of what people experienced and how communities later recounted those years.

Policy reversal and attempts at remediation

An official change of course arrived after the scope of shortages became undeniable. Authorities removed sparrows from the Four Pests list around 1960 and redirected public campaigns toward other targets. External assistance included Soviet shipments of Eurasian tree sparrows and releases meant to re-establish bird populations. Those corrective actions acknowledged error in policy and practice but ecological recovery and social repair required time that hungry people did not have. The reversal recorded in government policy stands as administrative recognition that the campaign had exceeded its intended goals and produced harmful effects.

Scholarly debate and continuing questions

Archival finds and improved demographic and environmental modeling help historians to better define judgments. Crucial lines of investigation currently center on local variance: which counties and ecological regions experienced the most marginal effects from bird removal and why did some local authorities more successfully moderate results than others? Demographers inquire how reliable the mortality reconstructions are and which fresh local records may reduce the vast ranges in estimates. Social historians investigate how survivor narrative was formed by memory and local politics. Though more effort is needed to tighten projections and to explain the variety of local results, integrating oral history, local archives, and contemporary empirical techniques has improved understanding.

The event in historical perspective

The eradication of sparrows from 1958 through roughly 1960 belongs in mid-twentieth-century Chinese history as a clear example of a policy experiment that made sense in its moment. That experiment offered an arithmetic, a civic ritual, and a visible task that delivered immediate recognition and social reward. Those features made the policy stick. The campaign’s outcomes show that policies operate inside living systems and that human institutions and natural systems interact in complicated, often surprising ways. Removing a widespread insectivore at scale produced effects that outlasted the ceremonies and amplified human suffering precisely because other policies had already weakened rural coping capacity.

Closing observation

Every time one looks back in time, balance is sought. Elimination of sparrows alone did not cause the Great Famine. Evidence indicates that the campaign was an unnecessary amplifier of a terrible collection of environmental stressors and laws rather than their only source.

Given its everyday appearance at the time, the Eradicate Sparrow Campaign is still among the most consequential events of the Great Leap Forward. It comprised of no clandestine preparations, no cutting-edge technology, and no far-off battlefield. Carried forward by ordinary people working inside an amazing political event, it unfolded in courtyards, fields, and village squares. The campaign demonstrates how mass involvement and a policy based on basic calculations might transform surroundings and livelihoods over a period of months. It reminds us as a historical event that state power does not necessarily run only via violence. It can also operate via passion, discipline, and communal faith, with results only apparent long after public mobilization subsided and the birds disappeared from the landscape.