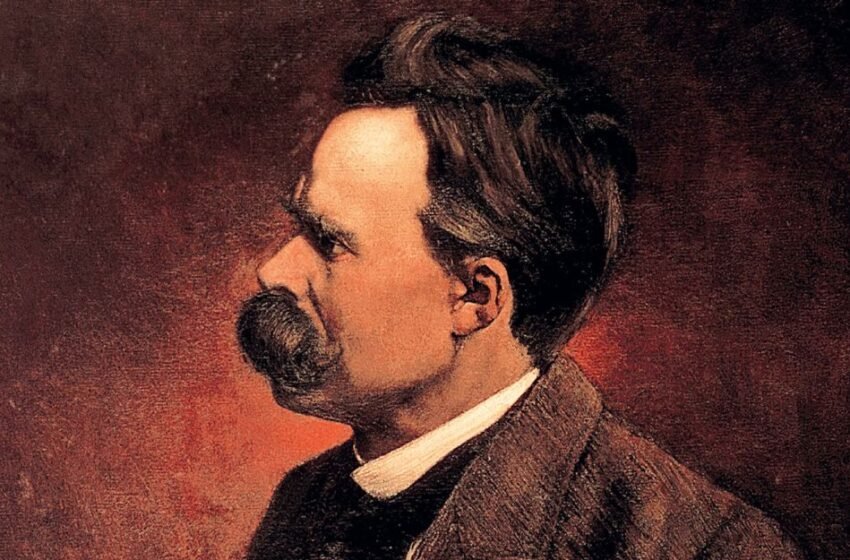

Nietzsche: The Thinker Who Redefined Truth

-Prachurya Ghosh

Introduction: Nietzsche and the Crisis of Modern Thought

Friedrich Nietzsche occupies a paradoxical position in modern intellectual history. He is celebrated as one of the most radical critics of Western metaphysics and morality, yet he remains one of the most controversial figures because of his views on women and religion. His philosophy is deeply disruptive: it challenges inherited moral systems, religious certainties, and social norms that had structured European thought for centuries. Two of the most debated aspects of his work are his critique of God—summarized in the provocative declaration that “God is dead”—and his reflections on women, which often appear misogynistic, ironic, or deliberately provocative. These two themes are not isolated from each other. On the contrary, Nietzsche’s ideas on women and God emerge from the same philosophical project: a radical revaluation of values aimed at exposing the psychological, cultural, and historical foundations of morality itself.

Historical Context: Nietzsche and Nineteenth-Century Europe

To understand Nietzsche’s position, one must situate him within the broader crisis of modernity in nineteenth-century Europe. This was a period marked by the decline of traditional religious authority, the rise of scientific rationalism, and the growing dominance of bourgeois morality. Nietzsche perceived this world as spiritually exhausted, clinging to moral ideals that no longer had a living foundation. His philosophy was not merely descriptive but diagnostic: he sought to reveal the hidden motives behind beliefs, especially those that presented themselves as universal truths.

The Meaning of “God is Dead”

Nietzsche’s critique of God is perhaps the most famous and most misunderstood aspect of his philosophy. When he announces the “death of God,” he is not making a simple atheistic claim that God does not exist. Rather, he is diagnosing a cultural condition: the collapse of belief in the Christian God as the ultimate source of meaning, truth, and moral authority. In works such as The Gay Science and Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche portrays this event as a catastrophe for Western civilization. God’s death signifies the end of an entire worldview that had structured European life for nearly two thousand years. Without God, there is no transcendent foundation for truth, no divine guarantee of moral values, and no cosmic purpose to human existence.

Nihilism and the Problem of Meaning

Yet Nietzsche does not celebrate this event uncritically. The death of God produces what he famously calls nihilism: the sense that life is meaningless, that all values are arbitrary, and that nothing truly matters. Modern humanity, in Nietzsche’s view, continues to live in the shadow of Christian morality even after losing faith in its metaphysical basis. Concepts such as equality, compassion, guilt, and self-sacrifice persist, but they are no longer grounded in a belief in God. They become, instead, empty habits—moral reflexes inherited from a dead tradition.

Christianity as Life-Denying Morality

Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity is particularly harsh because he sees it as a life-denying religion. He argues that Christianity glorifies weakness, suffering, and humility while condemning strength, power, and creative vitality. In his Genealogy of Morality, he develops the concept of “slave morality,” a moral system created by the weak to protect themselves against the strong. According to Nietzsche, values such as meekness, obedience, and altruism are not universal moral truths but psychological strategies developed by those who lack power. Christianity, in this sense, represents a moral revolution in which resentment becomes virtue and strength becomes sin.

The Übermensch and the Revaluation of Values

This critique of God leads directly to Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch, or “overman.” The Übermensch is not a biological or racial ideal, but a philosophical one: a figure who creates new values in a world without divine authority. If God is dead, humanity must become its own legislator, inventing meanings and goals instead of inheriting them. The Übermensch embodies self-overcoming, creativity, and affirmation of life. He does not seek comfort in metaphysical illusions but embraces the tragic, uncertain nature of existence.

Nietzsche on Women: Provocation and Prejudice

Nietzsche’s reflections on women must be understood within this same framework of value-critique. On the surface, his statements about women often appear deeply misogynistic. He frequently portrays women as manipulative, irrational, and fundamentally oriented toward deception. One of his most infamous lines, “You are going to women? Do not forget the whip,” has been endlessly quoted as evidence of his hostility toward women. Yet such statements cannot be taken at face value without considering Nietzsche’s distinctive style. His writing is aphoristic, ironic, and deliberately provocative. He exaggerates, mocks, and destabilizes conventional language in order to expose hidden assumptions.

Woman as Metaphor: Truth, Illusion, and Appearance

Nevertheless, it would be dishonest to deny that Nietzsche often reproduces traditional gender stereotypes. He associates women with appearance rather than essence, with artifice rather than truth, and with emotion rather than rationality. In this respect, he remains deeply embedded in nineteenth-century European patriarchal culture. Women, for Nietzsche, often symbolize illusion, seduction, and the power of surfaces. They are linked to masks, cosmetics, and theatricality—elements that Nietzsche simultaneously criticizes and admires. His famous remark that “truth is a woman” suggests that truth itself is elusive, seductive, and resistant to rigid conceptualization.

Will to Power and Gender Relations

The relationship between Nietzsche’s views on women and his critique of God becomes clearer when one considers his understanding of power. For Nietzsche, all human relationships are expressions of the “will to power”—the fundamental drive to assert, expand, and intensify one’s existence. Religion, morality, gender relations, and even philosophy itself are arenas in which this will to power operates. Christianity disguises power under the language of humility and love, while gender norms disguise power under romantic ideals of femininity and masculinity.

Feminist Critiques and Reinterpretations

From a contemporary perspective, Nietzsche’s views on women are among the weakest aspects of his philosophy. Feminist thinkers have pointed out that his celebration of strength and creativity often relies on the exclusion or marginalization of women. His ideal human types—the philosopher, the artist, the overman—are almost always implicitly male. Yet some feminist philosophers have also found resources in Nietzsche’s thought, particularly his critique of fixed identities and his emphasis on becoming rather than being.

The Ambivalent Legacy of Nietzsche’s God

The same ambivalence characterizes Nietzsche’s legacy on religion. He is often celebrated as a heroic atheist, but his position is more complex than simple disbelief. He does not merely reject God; he mourns the cultural consequences of God’s disappearance. Religion provided not only metaphysical illusions but also emotional comfort, moral orientation, and social cohesion. The death of God leaves humanity exposed to existential anxiety and moral uncertainty.

Conclusion: Nietzsche as a Philosopher of Disruption

In conclusion, Nietzsche’s treatment of women and God cannot be separated from his broader project of revaluating all values. His declaration of the death of God announces a radical cultural rupture, challenging humanity to create meaning without divine authority. His provocative statements about women reflect both his symbolic critique of illusion and his embeddedness in patriarchal discourse. Together, these themes illustrate the double edge of Nietzsche’s thought: it is simultaneously emancipatory and problematic, liberating and exclusionary. Nietzsche does not offer comforting truths; he offers unsettling questions. And it is precisely this unsettling quality that makes his philosophy continue to provoke, disturb, and inspire more than a century after his death.