The Untold Story of Begum Samru, India’s Warrior Begum

-Prachurya Ghosh

Introduction: A Woman Who Defied Her Age

In the story of late eighteenth-century India, one would indeed be remiss not to mention the extraordinary life and contributions of Begum Samru, a woman who defied almost every social, political and gendered norm of her time. Rising from extreme poverty to become one of the most powerful military and political figures of North India, Begum Samru stands as one of the most remarkable examples of female agency in early modern Indian history. Her life cuts across categories of class, religion, gender and empire, making her not merely a historical curiosity but a deeply significant figure in understanding the transitional world between Mughal decline and British ascendancy.

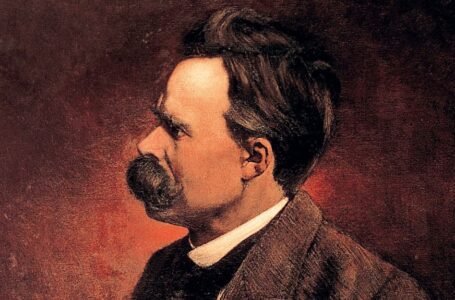

Visual Culture and Representation

Begum Samru is usually depicted in late Mughal or early Company-style miniature paintings, where her visual representation itself becomes part of her historical meaning. These portraits typically show her as short in stature, fair-complexioned, often elderly, and richly adorned in expensive jewellery and embroidered garments. In several paintings she is wrapped in Kashmiri shawls, a detail that signifies both elite status and her claimed Kashmiri ancestry. Some images present her in solitary authority, seated with a hukka in hand like a traditional Mughal noble, while others portray her surrounded by courtiers or even leading troops into battle. These representations were not accidental but functioned as political symbols, projecting her simultaneously as a Mughal aristocrat, a sovereign ruler and a military commander.

Early Life and Social Marginality

Born as Farzana in the early 1750s to a family of impoverished Persian nobility, her early life was shaped by economic decline and social insecurity. The weakening of Mughal patronage networks meant that minor noble families were often reduced to survival strategies that lay outside elite respectability. Farzana’s circumstances forced her into becoming a nautch girl in Delhi’s Chawri Bazaar, a space commonly associated with moral stigma but also one that operated as a centre of cultural exchange. These spaces enabled women to acquire linguistic skills, political awareness and social intelligence, all of which later proved crucial in Farzana’s transformation into a powerful political actor.

Marriage and the Birth of Begum Samru

Her life took a decisive turn in 1765 when she encountered Walter Reinhardt Sombre, an Austrian mercenary general serving various Indian powers. Their marriage in 1767 transformed Farzana into Begum Sombre, later immortalised as Begum Samru. However, she was never merely a dependent wife. From the beginning she was actively involved in military and financial affairs, operating as an equal partner in Reinhardt’s enterprise. When Reinhardt died in 1778, she inherited both his wealth and his army, assuming direct command over European-trained troops and artillery, an almost unprecedented position for a woman in eighteenth-century India.

Military Career and Political Strategy

Begum Samru’s military career demonstrated exceptional strategic skill and political adaptability. She maintained a disciplined standing army and became a crucial power broker in North Indian politics. Her support was instrumental to Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II during periods of political instability, and she aligned herself with the Marathas in resisting British expansion. At the same time, she negotiated pragmatically with the Sikh confederacy and Company officials whenever necessary. Her alliances were not driven by ideology but by survival and autonomy, allowing her to preserve sovereignty at a time when most Indian rulers were losing theirs.

Administration, Justice and Cultural Patronage

Beyond warfare, Begum Samru was also a capable and often admired administrator. In her territory of Sardhana she implemented systems of revenue collection, ensured public order and governed with notable fairness. Contemporary European accounts frequently described her as tolerant and just. She emerged as a major patron of art, literature and architecture, building palaces in Sardhana, Jharsa and Chandni Chowk. These structures symbolised not only wealth but political legitimacy, asserting her right to rule within a cultural framework that blended Mughal and European traditions.

Conversion and Religious Identity

One of the most striking aspects of her life was her conversion to Catholicism in 1781, when she adopted the name Joanna Nobilis Sombre. This act was both spiritual and political. Through Christianity she forged closer links with European powers and missionaries while retaining control over a religiously diverse population. She displayed remarkable tolerance, funding Hindu temples, Muslim institutions and Christian churches alike. Her greatest architectural legacy, the Basilica of Our Lady of Graces in Sardhana, remains one of the finest colonial churches in India and stands as a powerful symbol of her hybrid religious and cultural identity.

Death and Historical Legacy

Begum Samru died in 1836 in her eighties, having lived through the decline of Mughal authority and the consolidation of British imperial power. Buried in Sardhana, she left behind immense wealth, monumental architecture and a unique political legacy. Standing at barely four and a half feet in height, she demonstrated that authority is not determined by physical power but by political intelligence and strategic vision. Farzana’s journey to becoming Begum Samru challenges dominant historical narratives by showing that women, former dancers, and cultural outsiders could occupy central roles in shaping Indian history.

Conclusion: Rewriting Indian Historical Imagination

Ultimately, Begum Samru represents a forgotten alternative history of India, one in which power was not exclusively male, not exclusively British, and not exclusively hereditary. Her life reveals that the late eighteenth century was not merely an age of decline and colonial conquest, but also a period of social mobility, experimentation and unexpected agency. Remembering Begum Samru forces us to rethink Indian history as a space where individuals could transcend class, gender and religious boundaries to create new forms of authority and belonging.