Susanna Anna Maria: The Mysterious Historical Landmark of West Bengal

-Prachurya Ghosh

Introduction: A Forgotten Woman of Empire

Susanna Anna Maria occupies a distinctive yet largely forgotten position in the social history of colonial India. Known historically as Begum Johnson of Calcutta, she belonged to the early generation of Eurasian Christian women who emerged in eighteenth-century Bengal, at a time when colonial society was still fluid and racial boundaries were not yet rigidly fixed. She was neither fully European nor fully Indian, but inhabited the in-between spaces created by empire. Her life allows us to explore how identity, gender, religion and power intersected at the micro level within colonial structures. Through her historical biography, her literary transformation in Ruskin Bond’s A Flight of Pigeons, and the surviving monument at Chinsura, Susanna becomes a lens through which the emotional and cultural complexities of empire can be understood.

Colonial Bengal and the World of Hybridity

Susanna Anna Maria was born around 1768 in a Bengal that was still a contact zone rather than a fully consolidated British colony. The Mughal political system was weakening, and European trading companies were expanding their influence across the region. Towns such as Calcutta, Chinsura, Chandannagar and Serampore became spaces of intense interaction between Indians and Europeans. Interracial relationships were common, and the children of such unions formed a growing Eurasian population. These individuals often lived within culturally mixed households, spoke multiple languages, practiced Christianity, yet remained deeply embedded in Indian society. Susanna emerged from this hybrid world. Her father was European, possibly a soldier or company official, while her mother was Indian. From childhood she experienced identity not as a fixed category, but as something negotiated daily through social interaction.

From Widow to Begum: Gender and Social Power

Susanna’s marriage to Charles Johnson, a British officer, placed her within the colonial elite. However, it was his death that marked the decisive transformation of her life. As a widow she inherited substantial wealth and property, making her economically independent in a deeply patriarchal society. She became popularly known as Begum Johnson, a title that itself reveals her cultural duality. The term “Begum” associated her with Indian aristocratic respect, while “Johnson” linked her to European lineage. This dual identity was not merely symbolic; it structured her everyday life. She adopted Indian dress and manners, maintained Indian servants, yet funded Christian missions and supported Eurasian education. Her house in Calcutta became a social centre, bringing together Indian elites, European officials and mixed-race families. In this sense, Susanna was not simply surviving within the empire but actively shaping its social world.

Liminal Identity and the Fragility of Belonging

Despite her wealth and influence, Susanna’s position remained fragile. She was a woman in a male-dominated colonial society, a Eurasian in an increasingly racialised social order, and a Christian living within a predominantly non-Christian cultural environment. Her authority depended largely on personal wealth and social networks rather than institutional power. As British racial attitudes hardened in the nineteenth century, people like Susanna found themselves increasingly marginalised. Her life thus reveals the instability of hybrid identities within colonial systems. She belonged to multiple worlds simultaneously, yet was never fully accepted by any of them. This liminality makes her historically significant because it exposes the emotional and social contradictions at the heart of empire.

From History to Fiction: Ruskin Bond’s Susanna

The historical Susanna re-enters cultural memory through Ruskin Bond’s A Flight of Pigeons, where she is transformed into the fictional character Susanna Labadoor. Although Bond sets his story during the 1857 uprising, decades after the real Susanna’s life, the emotional profile remains closely connected. Bond’s Susanna is a young Eurasian Christian woman who loses her father and becomes dependent on the protection of an Indian rebel leader. Unlike the historical Susanna, who exercised economic and social power, Bond’s Susanna is vulnerable, fearful and morally conflicted. This shift reflects Bond’s literary purpose. He is less interested in documenting power and more concerned with exploring emotional experience. Through his Susanna, colonial history becomes a story of trauma, displacement and moral ambiguity rather than administrative control.

Literature as Emotional History

Ruskin Bond’s version of Susanna does not replace the historical figure but reinterprets her through feeling. The real Susanna negotiated authority through wealth and patronage, while the fictional Susanna embodies the psychological insecurity of living between cultures during political violence. Bond uses her as a moral witness rather than a social actor. Through her perspective, the rebellion of 1857 appears not as a simple nationalist struggle or colonial crisis, but as a deeply human tragedy. This literary transformation highlights the limits of official historical archives. While documents record property, dates and institutions, literature captures fear, confusion and emotional vulnerability. In this sense, Bond’s Susanna reveals what history often cannot: the inner life of colonial subjects.

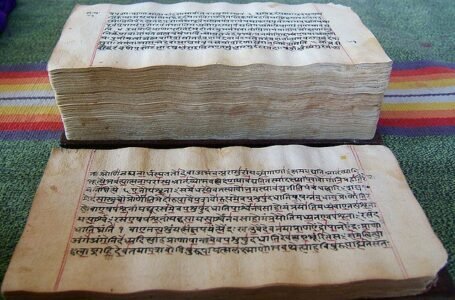

The Monument at Chinsura: Architecture and Memory

The most concrete historical trace of Susanna Anna Maria is her monument at Chinsura in the Hooghly district of Bengal. Located near the old Dutch cemetery, the monument is built in neoclassical European style, with English inscriptions and a prominent physical structure. This architectural choice reflects her desire to be remembered within a European-Christian cultural framework. Yet its location in Bengal, surrounded by Indian landscapes and colonial ruins, symbolises her hybrid identity. The monument functions not merely as a grave but as a site of memory, transforming private life into public history. It stands as rare evidence of Eurasian female commemoration in a society where women’s lives were seldom recorded.

Microhistory and the Human Face of Empire

Studying Susanna Anna Maria through microhistory allows us to understand empire as a lived experience rather than an abstract system. Through her, colonialism appears not only as political domination but as a network of intimate relationships, cultural negotiations and emotional struggles. She reveals how identity was continuously produced through social interaction rather than inherited as a fixed category. Her life shows that colonial power operated not only through institutions but also through households, marriages, patronage and memory.

Conclusion: Why Susanna Still Matters

Susanna Anna Maria matters because she represents a category of historical actors who are often excluded from grand narratives. She was not a ruler, not a rebel, not a nationalist hero, but a cultural intermediary whose life silently shaped colonial society. Through her historical biography, Ruskin Bond’s literary reinterpretation, and her monument at Chinsura, she becomes a symbol of the forgotten intermediaries of empire. Her story forces us to rethink colonial history not as a simple binary of domination and resistance, but as a complex human world filled with ambiguity, negotiation and unresolved belonging. In remembering Susanna Anna Maria, we recover not just a single woman, but an entire social reality that colonial history tends to erase.