Beyond the Myth of Remoteness: Timbuktu as a Knowledge Society

-Oishee Bose

For centuries, Timbuktu has lived in the global imagination as a contradiction. On modern maps and in popular speech, it is invoked as a synonym for remoteness, a place at the edge of the world, distant from centres of power and thought. Yet the manuscript record left behind by its scholars tells a story that unsettles this image at every turn. Far from being isolated, Timbuktu was deeply enmeshed in intellectual circuits that stretched across the Sahara and into the wider Islamic world. Ideas, books, and people moved through the city with the same regularity as salt and gold, and the traces of those movements remain visible in the margins, colophons, and ownership notes of thousands of surviving manuscripts. The tension between myth and archive is not incidental; it is precisely where Timbuktu’s historical significance lies.

This contradiction becomes sharper when we consider what kind of knowledge was produced there. Timbuktu was never a museum of inherited texts, nor a passive recipient of distant traditions. It functioned as a working laboratory of knowledge, where thinking was tied to the demands of everyday life. Jurists drafted fatwā that settled disputes in bustling markets and regulated marriage, inheritance, and credit. Astronomers calculated tables that determined prayer times and agricultural rhythms. Healers compiled pharmacopoeias that blended classical medical theory with desert herbs and local experimentation. Copyists, students, and patrons produced and preserved manuscripts that families guarded as intellectual and moral heirlooms, passing them down alongside property and lineage memory. Knowledge here was not abstract; it was practical, contested, and continually renewed.

Geography, Trade, and the Material Foundations of Learning

The conditions that made Timbuktu possible are prosaic and material. Its location near the Niger bend and at the southern terminus of major trans-Saharan routes meant that human beings and bundles moved with regularity: merchants, pilgrims, scribes, and returning students brought books as easily as they brought salt or textiles. Pilgrims returned with books, students travelled in search of teachers, and jurists corresponded across vast distances. Timbuktu’s location did not inhibit intellectual life; it structured it. Arabic became the functional lingua franca for liturgy, law and administration, and the spread of Islamic institutions, mosques, qāḍī courts and teaching circles generated stable demand for literacy. However, Islam in the Sahel adapted: local rhythms and knowledge practices were translated into written form rather than erased. That is why alongside Arabic texts we find extensive Ajami material which is African languages written in Arabic script, preserving poems, medical recipes, trade formulas and local administrative records. Trade supplied circulation; Islam supplied demand; local social forms (households, markets, saints’ networks) determined how learning actually worked.

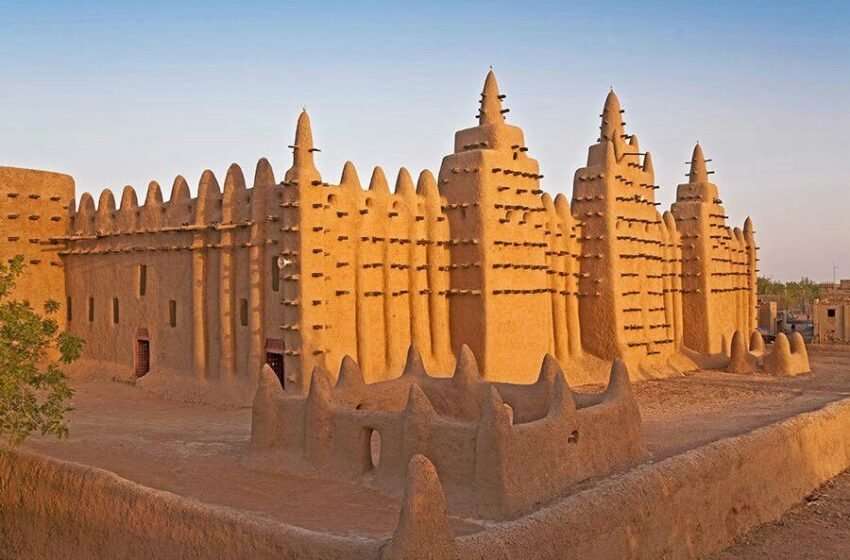

A Distributed Intellectual Ecology: Mosques, Households, and Movement

Timbuktu’s institutional ecology was not a university in the European sense; it was a federated, distributed system in which mosques, household libraries, itinerant teachers and market brokers all played complementary roles. The Sankoré, Djingareyber and Sidi Yahya mosques were visible anchors, public places of instruction and debate but much of teaching happened in private homes and in courtyards under acacia shade. Households were not passive storehouses: they were active sites of instruction, copying and curation. Families curated and expanded libraries across generations; what modern historians often imagine as state archives, the lived reality was that these lineages were the archival institutions. The Haidara household, for example, developed and preserved a broad, ecumenical corpus — law, theology, medicine, poetry and contracts which later formed the backbone of a major family library. The Aqit lineage functioned across generations as jurists and qāḍīs, their fatāwā and local casebooks forming reference collections used to settle disputes. The Baghayogho households were pedagogical anchors around Sankoré, leaving heavily used teaching copies and student exercises. The Kati household is associated with chronicle writing, genealogies and interpretive histories used to claim legitimacy. Smaller clerical families, often called by the general label “Alpha” in local usage maintained the Qur’anic primers, recitation notebooks and base juridical primers that sustained community literacy. These families did were the institutions through which pedagogy, authority and custodianship were reproduced.

Learning by Hand: Pedagogy, Transmission, and Student Life

Pedagogy was embodied and manuscript-centred. Students learned through dictation, line-by-line copying, memorisation and oral explication; the production of a manuscript was itself an exercise in apprenticeship. Chains of transmission (isnād) and ijāzahs (written authorisations) tied individual students to masters and to textual lineages; families carefully preserved ijāzahs as part of their documentary capital. Student life was austere and communal: early morning recitation, long copying sessions, evening commentary and the occasional disagreement recorded in a margin. The manuscripts that survive are palimpsests of these practices, which are main texts surrounded by sharḥ (commentary), ḥāshiya (gloss), marginal emendations, corrections, ownership notes and even prayers for the text’s protector; some colophons record the name of the copyist, the patron, the city of origin, and sometimes the fee paid. Those marginal traces are the human record of classroom friction, ambition, correction, and continuity.

Manuscripts as Social Objects: Materiality, Markets, and Care

Materially the manuscripts are social objects with lifecycles. Paper (often rag paper arriving via North African trade), leather bindings, and inks made from local and imported compounds were the raw materials; the finished book was used, repaired, rebound, annotated and sometimes cannibalised for bindings. Families developed practical storage methods by wrapping folios in cloth, stowing volumes in chests and hidden niches to protect against humidity, insects and theft and the Haidara custodial techniques later proved decisive when rapid evacuations became necessary in the modern era. A functioning local book market and scribal economy sustained this culture: professional scribes were hired for neat copy and marginal notation; merchants commissioned copies for legal certainty or prestige; rare works could command high prices and even be used as collateral. It is no exaggeration to say that in certain contexts a manuscript’s social value rivalled that of gold.

What Was Written: Genres, Hybridity, and Everyday Use

The corpus itself is capacious and hybrid. Jurisprudence and collections of fatāwā (many preserved in Aqit casebooks) coexisted with Qur’anic exegesis, Hadith collections, Sufi treatises, astronomical tables and almanacs used for qibla calculations and prayer times, medical compendia blending Greco-Islamic theory and local herbal lore (common in Haidara and Alpha households), chronicles and genealogies associated with Kati circles, poetry, didactic literature and mundane documentary genres like contracts, wills, tax rolls and merchant correspondence. Often, a single notebook combined genres: a legal opinion sitting beside a marriage contract and a mnemonic poem; marginal notes might record a student exercise and an annotator’s objection. This hybridity matters because it reveals how knowledge was woven into daily life rather than kept in a disciplinary museum.

Plural Traditions and Intellectual Contestation

Intellectual life was plural and argumentative. Maliki jurisprudence structured much public reasoning, but jurists repeatedly debated matters of marriage, inheritance, taxation and the obligations of rulers; crucially, women appear in the records as litigants and property holders, showing that legal practice was responsive to local claims. Sufi orders contributed devotional manuals and litanies that circulated within households and merchant networks, sometimes reinforcing, sometimes contesting juristic authority. Scientific practice was pragmatic: astronomical tables were crafted for community needs and medical remedies blended observation with inherited doctrine. Debate and polemic left their traces in the corpus — corrected lines, crossed-out passages, rebuttals in margins and reveal an intellectual culture resistant to simplistic “harmony” narratives.

Scholars, Lineages, and Human Lives of Knowledge

Named actors make this social history concrete. Ahmad Baba’s career and writings show both the height of Timbuktu’s legal culture and its vulnerability: his prolific output, teaching, and eventual exile illustrate how political rupture could displace an intellectual network without erasing its textual life. The Aqit family’s fatāwā codices map how law regulated urban life; the Baghayogho pedagogical copies document transmission in action; Kati chronicle manuscripts demonstrate history used as moral and political argument; Haidara family archives show the curatorial labour of preservation across generations; and Alpha lineages preserve the everyday Qur’anic and juridical primers that kept collective literacy functioning. These households were not mere proprietors; they were the social machines that produced, transmitted and protected knowledge.

Rupture, Reconfiguration, and Long Survival

The longue durée of this culture is marked by rupture and resilience. The Moroccan expedition of 1591 fractured the Songhai political order, produced deportations and dispersals of scholars and interrupted the patronage networks that underwrote public institutions. Subsequent redirections of trade toward Atlantic routes further weakened the mercantile base that supported lavish patronage. Colonial educational regimes later privileged European curricula and languages, displacing many traditional pedagogies from the public sphere. Yet, intellectual life continued in private: copying, teaching and legal adjudication persisted in households and diasporic networks. Decline, in other words, was reconfiguration rather than annihilation; family libraries and itinerant scholars carried the tradition forward.

Crisis and Custodianship in the Contemporary Moment

The modern crisis of 2012 brought this custodial ethic into stark relief. When violent actors targeted shrines and repositories, it was local librarians, families, religious leaders and ordinary citizens who smuggled manuscripts to safety by packing fragile folios into sacks, loading them onto boats and trucks, and shipping them to clandestine storage. The Haidara family’s archival practices and local networks enabled rapid mobilisation; their centuries of custodianship were not only cultural memory but practical knowledge for emergency preservation. Today digitisation, conservation and repatriation initiatives have made many texts accessible to global scholarship but those interventions raise urgent ethical questions about ownership, access, and benefit: who controls digital surrogates; how are custodial communities compensated and how can scholarship avoid repeating extractive patterns? The only sustainable path forward is one centred on local agency: training Malian conservators, co-governed digital repositories, and research agendas designed in partnership with custodial lineages.

Emerging Research and the Future of the Archive

New research frontiers converge now around the smallest traces: Ajami notebooks that reanimate vernacular science and commercial practice; marginalia and colophons that reveal student networks, patronage ties and emotional attachments; microhistories of contracts, medical recipes and marriage records that reconstruct everyday law; codicological studies of inks, bindings and paper origins that reveal trade routes; and digital-humanities projects mapping citation and transmission networks across households and mosques, all of which together reposition Timbuktu from exotic footnote to a central case in theories of knowledge circulation, legal pluralism and the social life of texts.

Conclusion: Knowledge as a Lived Inheritance

The intellectual history of Timbuktu reveals a culture in which knowledge endured not through monumentality or centralised control, but through everyday social practice. Learning survived because it was embedded in households, lineages, and routines of care that treated manuscripts as working tools rather than inert relics. Texts were copied, annotated, repaired, and transmitted across generations, their authority sustained through relationships between teachers and students, jurists and communities, families and their books.

This decentralised structure proved remarkably resilient. When political patronage collapsed and public institutions weakened, intellectual life did not disappear; it reorganised itself within private libraries and itinerant networks. Timbuktu’s manuscript tradition thus challenges modern assumptions about how scholarship is produced and preserved. The surviving texts are not simply historical sources but material traces of long-term custodianship, reminding us that intellectual cultures persist not only through ideas, but through the social labour that keeps those ideas in use.