The Curse of Kings: Legendary Dooms and Historical Realities

-Ananya Sinha

Power has ever been a double-edged sword. Kings and leaders over the centuries have been in a self-contradictory role, graced with divine right or periodic charisma, but haunted by rumour of treachery, downfall, and devastation. In cultures everywhere, the legend of a ruler’s curse, either divine or moral retribution, or symbolic prophecy, has served to account for past unrest and warn future rulers. The meeting of mythic curses and the political facts of fallen regimes illustrates how morality, memory, and mythal interact to create the experience of kingship.

This essay is a discussion of the motif of cursed kings, developed from myth, chronicles, and history, and how these tales symbolize symbolic fears and political reality. From the grandeur of Mesopotamian epics to the morality tales of European monarchs, the curse of kings is both a literary convention and a historical necessity.

I. The Symbolism of Cursed Sovereignty

In myth and legend, curses may function as a literary device to account for the fall of kings or dynasties. The king, being divine, has a responsibility to uphold justice, piety, and order; defaulting this, the curse makes an appearance as divine judgment. This literary device conceals a hidden moral flaw: that ambition and pride with no checks will necessarily result in disaster.

The motif occurs starkly in Greek legend. The king of Thebes, Oedipus, is not only cursed by fate but also by the parricide and incestuous guilt incurred unknowingly. His curse is infectious, destroying his household and covering Thebes in sorrow. The myth symbolizes the Greek belief that kingship, no shield from fate, at times harbors human weakness. Similarly, in the House of Atreus, patterns of violence and treachery topple kings who are unable to flee curses they inherited.

In India, the Mahabharata records the fate of King Dhritarashtra, blind both in sight and judgment, whose indulgence of his sons leads to the destruction of his lineage. Curses are invoked explicitly in the epic—such as Gandhari’s curse on Krishna for failing to prevent war—illustrating how divine justice unfolds through human tragedy. Here, curses serve not merely as supernatural devices but as moral commentaries on flawed rulership.

II. Legendary Dooms and Historical Kings

The line between history and myth is easily crossed in the royal legend. Real kings, disgraced, banished, or murdered, were routinely remembered in terms of curses. Sometimes curses were specifically uttered by chroniclers or detractors to explain otherwise unexplainable collapse of authority.

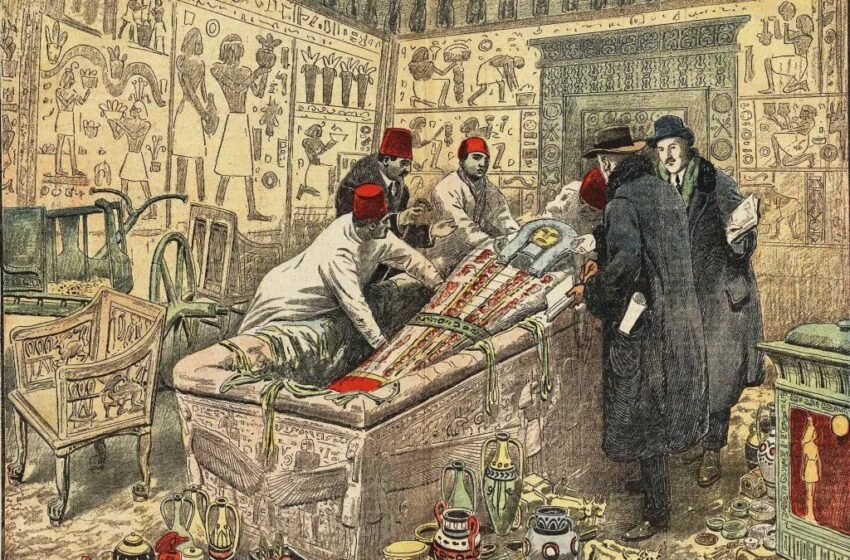

1. The Pharaoh’s Curse

Egyptian pharaohs, gods on earth, were believed to wield power even in death. The alleged “curse of the pharaohs” gained notoriety in 1922 with the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb, when several members of Howard Carter’s team of laborers mysteriously died. While death from infection or accident is now attributed by modern science, the myth continues to be a sign of divine wrath upon violators of royal sanctity. The tale is typical of the cultural mandate that kingship, especially divine kingship, transcends mortality in mythical warning.

2. The Fall of the Capetian Kings

The medieval French dynasty of the Capets was involved in one of the greatest mythological royal curses. When King Philip IV warred against the Knights Templar and they lost, and their Grand Master Jacques de Molay was executed by being burned at the stake in 1314, de Molay cursed the king and his dynasty from the fires. Interestingly enough, Philip IV and all his sons perished within one generation, and France was faced with a crisis of dynasty that would eventually cause the Hundred Years’ War. Coincidence or fabrication as it may have been, the legend kept alive the dangers of sacrilege and hubris.

3. The Stuart Curse in Britain

The Stuart dynasty was remembered in England and Scotland with a spine-tingling feeling of dread. From the assassination of Charles I in 1649 to James II’s flight in 1688, Stuart monarchs alike suffered conflict, betrayal, and violent demise. Later writers accounted for these tragedies as a dynastic curse caused by violated vows, forced marriages, or the wrath of God. The curse theme within these works was a political upheaval rationalization offered by later historians using hindsight, imposing a mythic moral explanation upon events.

III. Political Use of the Curse Legend

Cursed monarchs are not an imaginary or arbitrary phenomenon; they have often been used as a political tool. Invoking a king as cursed dis-legitimizes his rule, mobilizes the opposition against him, or explains catastrophes.

Medieval and early modern European chroniclers invoked curses regularly in order to legitimize rebellion or deposition. To cite one famous instance, the English Richard III, who died fighting in 1485, was subsequently demonized by Tudor chroniclers, who attributed that he had been cursed for having killed his nephews in the Tower. Not only did this curse-tainted account wish away Richard’s legitimacy but also canonized the advent of the Tudors as God’s doing.

And thus, in South Asian histories, the defeat of oppressive kings is typically attributed to curses by saints’, sages’, or downtrodden subjects. These histories legitimized the moral order of dharma—the order of morals which the ruler must defend. A curse was therefore a divine punishment and political warning: injustice would not go unpunished.

IV. The Curse as Historical Pattern

Apart from myth and manipulation, there is a profound psychological and political reality in the motif of cursed kings. Absolute power will keep rulers separated from their people and subjects and subject to paranoia, treachery, and error. Dynasties will topple most often due to internal dissension, external aggression, or the decay that inevitably goes with long-term power. The “curse” here is just a historical trend that can be observed by one and not something supernatural.

Hubris—in the form of overexpansion, excess, or abandoning counsel—has time and again brought down the governing powers. Consider Napoleon, whose brilliant career saw him ascend to the throne; whose ambition to conquer Europe; sealed his doom. Although not put in mythic terms, his trajectory is the same height followed by inexorable collapse.

Even now, the “curse of power” dogs leaders. Dictators who ascend to power on a platform of reform inevitably end up in exile, ignominy, or a firing squad. The image of the accursed ruler thus evolves beyond the royal realm, to become a comment on the frailty of power, universally applicable.

V. Myth, Memory, and the Continuing Power of the Curse

The persistence of royal curses in groups’ collective memory is evidence of the symbolic power of such stories. They serve as narrative anchors, redeeming obstreperous history as moral parables. Not only does a curse explain why kings fall, but also why societies are remade. By inscribing collapse as the consequence of divine vengeance, societies can encapsulate the shock of dislocation with a worldview of cosmic justice.

In addition, curses humanize kings. They strip from them the atmosphere of invulnerability and remind subject and sovereign alike that power cannot exceed mortality, or goodness. The divine-by-title king is subject to the same laws of justice and fate as all of mankind.

Conclusion

The curse of kings, whether or not mythic, is a rich metaphor for the weakness of power. Doomed-ruler myths, from Oedipus to Dhritarashtra, illustrate how curses inscribe cultural discomfort with justice, hubris, and the divine order. Historical examples, from the collapse of the Capetians to the Stuarts’ troubles, illustrate how curses were called on to explain political collapse and ritualize popular memory. Deeply, the trope is a historial reality: power unchecked creates its own demon.

The mythic dooms of kings survive not on their otherworldly credibility, but because they draw out a timeless truth of leadership: that every throne contains ruin’s shadow. The crown is as much curse as blessing, and history, as myth, teaches us that kings blinded to this balance inevitably march to their doom.