The Archaeology of Epic Battles: Separating Heroic Verse from Historical Warfare

–Ananya Sinha

Human history is preserved not merely in inscriptions and chronicles but also in the songs, epics, and myths preserved by generations as cultural memory. Among the most enduring of these histories are epic tales of wars—tall tales of gods and heroes engaged in battles which shaped civilizations. Epic poems like Homer’s Iliad, India’s Mahabharata, or Mesopotamia’s Epic of Gilgamesh contain graphic descriptions of war with abundant details of weapons, strategies of warfare, and emotions of men. Historians and archaeologists are always left trying to find out: how much of these epics are true, and how much is the product of poetic license?

The task of sorting out history and myth, and exaggeration and actual conflict, has caused scholars to turn to archaeology. Ruins dug up, fragments of weapons, burial sites, and ramparts provide a material counterpart to verses. Epic battle archaeology is thus a fascinating inter-disciplinary venture—one that attempts to discover where myth transitions into history.

Epic Poetry as Cultural Memory

Epics were not entertainment in themselves; they were memory banks shared among people. Oral tradition preserved required cultural values and teachings in rhythm and verse to make remembering easier. In war reporting, these epics provided society with the heroic models of bravery, loyalty, and sacrifice.

For example, the Iliad praises Achilles’ rage and Hector’s valor, while the Mahabharata describes a cosmic battle between dharma (moral responsibility) and kin. These epics transcended being accounts of war; they were paradigms through which society understood human tragedy, fate, and divine purpose. However, because they were founded on embellishment and metaphor, it is no simple exercise to separate their historical nucleus from poetic hyperbole.

Archaeology as a Corrective Lens

Archaeology is a means for verifying, locating, or disproving epic tales. By examining settlements, weapons, and tombs, archaeologists can decide whether huge wars of the kind described in epics were feasible at the times involved.

For example, Homer describes Troy as a thriving town with strong defenses. Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations in the late 19th century uncovered an archaeological site at Hisarlik in modern Turkey that produced several settlement layers. One of them, Troy VIIa, contained evidence of its destruction around 1200 BCE, approximately the time when the Trojan War is believed to have happened. While Schliemann’s method was crude, later systematic excavations confirmed that the site was indeed a great trading center, rebuilt and destroyed many times. While archaeologists cannot be certain that Homer’s vivid characters existed, they can confirm that a war involving Troy was plausible.

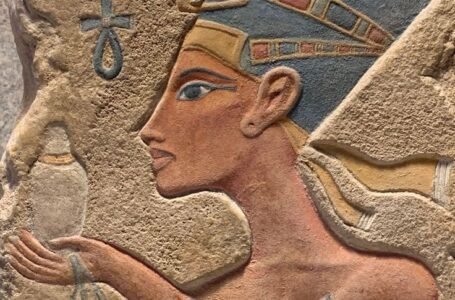

Similarly in India, the Mahabharata speaks of Kurukshetra as the battlefield upon which rival cousins fought a gigantic battle. Archaeological digs in Kurukshetra and surrounding areas have yielded Iron Age habitations, grey ware painted pottery, and weaponry dating from 1000–800 BCE, roughly consistent with scholars’ predictions for the epic’s temporal period. While no single archaeological site verifies the gigantic scale of war described in the text, the archaeological artifacts verify that the region was in fact a settlement and warfare center.

Heroic Verse vs. Battlefield Reality

The use of epic language elevates war to a heroic or cosmic drama and far from the common brutality. The warriors are portrayed as superior entities, their weapons being charged with divine energy, and their armies being in the order of millions. Archaeology suggests more restricted orders of war in real life.

For instance, the Mahabharata speaks of the use of celestial weapons (astras), which would kill thousands of soldiers at one go, and in people’s imagination are equated with modern-day artillery or even nuclear warfare. Archaeology, however, suggests iron arms—the sword, spear, and arrow—as war weapons. There is no evidence for millions of military personnel; strategic facts of food, water, and land would have maintained army strength far below numbers. The numbers of epics, therefore, are overstated for purposes of expanding the grandeur of war.

In the same way, the same applies to Homeric warfare. While the Iliad narrates duel-like combat between demigod-like warriors with glittering bronze armor, archaeological digs at Mycenaean sites yield pragmatic armor, such as the Dendra panoply, for protection and not poetry. The discoveries show that the combat was carried out using orderly ranks and practical weapons, much less romanticized than in Homeric verse.

The Role of Collective Memory

The exaggeration of epics cannot be attributed to fiction. They are images of the activities of collective memory. Societies did not remember battles as fact from history but as moments of existential significance. Societies remembered not just the fact of war but its emotional and moral significance through magnification.

Thus, while the Iliad can’t be read literally as a record of a war, it preserves the memory of a Late Bronze Age conflict between Troy and the kingdoms of the Aegean. And the Mahabharata stores memories of wars and social-political upsets in the Indian subcontinent at the time of the shift from pastoral to settled agrarian society.

Archaeology’s Limits and Possibilities

While archaeology undergirds epic narratives, it also possesses limits. Material remains don’t “prove” an epic battle in the narrow sense of a modern-day record. Remains of destroyed walls or incinerated strata may indicate conflict, but they can’t determine whether Achilles fought Hector or Arjuna killed Karna.

Moreover, oral traditions do evolve. The epics were composed and collected centuries later than the purported events, and therefore poetic invention over historical cores. Archaeology is therefore best employed to illuminate the settings of the epics: the topography, economies, and technologies which might have underpinned such wars.

However, archaeology is enormously promising. The most recent advances in archaeogenetics, satellite remote sensing, and residue analysis enable more precise reconstructions of ancient wars. Isotopic analysis of skeletons, for example, can reveal diets, mobility, and even injuries consistent with war. Such techniques tell us more about ancient battlefields, moving beyond myth into human reality.

Comparative Perspectives: Beyond Homer and Vyasa

The epic warfare phenomenon cannot be confined to India and Greece alone. In Mesopotamia, the Epic of Gilgamesh depicts fights with gods and monsters in analogy to real wars between city-states. Archaeology at Uruk and other Sumerian cities confirms the supremacy of defense walls, verifying the epic depictions of city rivalry, though the perceived enemies could have been mythologized.

In the Hebrew Bible, such conflicts as the conquest of Jericho or David’s battles with the Philistines receive reverberations in archaeologically discovered Levantine conflict of the Late Bronze and Iron Ages, although typically with texts in conflict with excavations. Such resonances suggest an international trend: epics inflate wars into cosmic struggles, while archaeology grounds them in human societies with fluctuating economies, migrations, and power contests.

Toward a Balanced Understanding

To separate war history from heroic verse is not to sully epics of their dignity, but to appreciate them in two levels. They are, on the one hand, literary masterpieces, offering profound lessons about human aspiration, morality, and the woeful cost exacted by war. And they are, on the other, echoes of historical wars—enlarged by common memory but rooted in actual wars fought by ancient societies.

Archaeology is thus corrective and supplement. It tempers poetic exaggeration with the testimony of human measure and functional fact, and insists that for all one’s Homer there must typically be a real war, re-formed by remembrance into myth.

Conclusion

The archaeology of titanic battles is a sophisticated blend of history and imagination. Epics like the Iliad and the Mahabharata were not intended to be objective histories; they were cultural milestones, which were a blend of fact and moral teaching. Archaeology does not confirm their every detail, but it establishes that behind their lines there were real wars, real cities, and real men.

Distinguishing verse of heroism from war is not so much the debunking of myths as it is describing how societies recalled the past. Epics preserved the emotional reality of war—its greatness, its devastation, its moral dilemmas—forever, while archaeology unearths the material traces of conflict. They both offer a fuller picture of human history’s ever-continuing embrace with war, where memory and history meet to create civilizations.