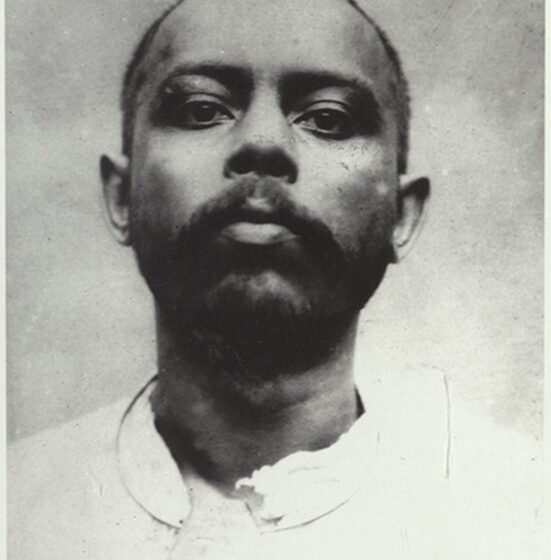

The Revolutionary Ullaskar Dutt

-Bhoomee Vats

Born in 1885, Ullaskar Dutt was part of an educated family staying in the village of Kaliakachha, Brahmanbaria, which is located in the Tipperah district of undivided Bengal (now in Bangladesh). His father first worked as an agricultural expert and later became a Professor in Civil Engineering College in Shibpur. Dutt was initially interested in the freedom struggle due to a fiery speech which was delivered in Star Theatre Hall by nationalist leader Bipin Chandra Pal (of the famous Lal-Bal-Pal trio). The speech was regarding the meek loyalists who were on the top of the Indian National Congress’ hierarchical pyramid. In his book “Twelve Years of Prison Life”, Dutt writes how it had a huge impact on him, he was then completing high school at City College, Calcutta (now Kolkata).

After a few months, he gave the entrance examination and got int Presidency College, which was then considered the most prestigious academic institution in the whole country, with the aim of studying chemistry. In the college he met Leela, who was the light-hearted daughter of Bipin Chandra Pal, and they fell in love. Around this time the British colonial government also announced its plan to partition Bengal (1905) which led to protest in the whole country and the launch of the Swadeshi movement. Ullaskar Dutt participated enthusiastically and as Bipin Pal was one of the main leaders of the protests, it can be assumed that his daughter Leela too was a participant.

The Anushilan Samiti and Alipore Bomb Case

In 1907, Barin created a “headquarter” for the Anushilan Samiti at a garden-house in the suburb of Maniktola. The headquarters were used by a group of young men who began to gather there and plan a form of armed resistance to the British occupation. Apparently, Aurobindo was not involved directly as he considered it premature, but the group was highly inspired by his fiery writings. Due to his knowledge of chemistry, Ullaskar Dutt became the group’s bomb-maker. This was followed by a couple of attacks on British officials. Unfortunately for the group, the police quickly traced the source to 36 Muraripukur Road, Maniktola, and many Anushilan Samiti members including the Ghosh brothers and Ullaskar Dutt was arrested.

The arrested young men would be lodged in Alipore Central Jail and tried at the Alipore Sessions Court. Thus, the case came to be known as the Alipore Bomb Case 1908. The twists-and-turns of the case, including a plot to escape, the smuggling-in of revolvers, and a gun-fight inside the jail, caused quite a sensation. Those interested in the details of these incidents can read about them in my book Revolutionaries (Harper Collins 2023).

Horror at the Cellular Jail

Transported to the Andamans, Ullaskar endured unimaginable brutality. Prisoners were yoked to oil mills like cattle, beaten mercilessly if they faltered. Ullaskar later wrote how bleeding bodies were dragged around the mills in circles of torment.

Punishments grew harsher. Once, after refusing work, he was shackled upright to a wall for days despite running a 107°F fever. Then came something unprecedented: jail authorities subjected him to repeated electric shocks using experimental batteries. He described the agony:

“The currents of electricity that passed through my body seemed to cut asunder all nerves and sinews, most mercilessly.”

After days of torture, he contemplated suicide. But the authorities, shaken by the recent suicide of fellow revolutionary Indubhushan Roy, stopped him. Instead, they declared him insane and transferred him to an asylum.

The Lost Years, Release, and Heartbreak

In 1912, Ullaskar was moved to the Government Lunatic Asylum in Madras. Cut off from his family, he drifted in hallucinations, often imagining conversations with Leela, though her name never appeared in his memoir—perhaps to protect her identity. Over the years he slowly regained stability, learning Tamil and working in the weaving shed. After World War I and the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, the British released several revolutionaries. In 1920, Ullaskar finally walked free after twelve lost years.

Reunited with his parents in Calcutta, Ullaskar immediately asked about Leela. The answer crushed him: believing him dead after years of silence, she had married another man. Later, when Ullaskar met her in Bombay, Leela explained she had written letters to him but none had been delivered—only one had ever reached him. Though devastated, Ullaskar accepted the truth and returned to Bengal.

Return to Activism, Partition and Reunion

Remarkably, he rejoined the freedom struggle, and in 1931 was jailed again for 18 months. After independence in 1947, irony struck—his ancestral village fell within East Pakistan, making him a foreigner in his own birthplace. Fate, however, had one final turn. Years later, Ullaskar learned that Leela, now a widow and paralysed, was living in Bombay. He brought her back to Calcutta and at last married his college sweetheart. The couple later moved to Silchar, Assam, where Ullaskar taught in a school for refugee children and cared for her until her death.

Conclusion

With a heavy heart, Ullaskar retuned to Bengal. He would write Twelve Years of Prison Life but, given that Leela was some else’s wife, she is never mentioned by name. Despite all that he had suffered, he would then go back to the revolutionary movement and again be sent back to jail for eighteen months in 1931. When he came out, he drifted back to his ancestral village of Kaliakaccha. He was living there when India was partitioned in August 1947. The man who had dedicated his life to India’s struggle for independence became a foreigner in his home at the moment that the country became independent. Some time later, as life became untenable for Hindus in East Pakistan, Ullaskar moved to Calcutta where he heard that Leela was now a widow and an invalid paralyzed from her waist down. So, he again went to Bombay and traced her. This time he brought her back with him to Calcutta. He then married her! So yes, Ullaskar Dutt did eventually marry his college sweetheart!

Life in Calcutta was difficult, however, as Ullaskar could not find a suitable job and Leela needed a lot of care. So, the couple moved to Silchar in Assam where many Bengali Hindus from east Bengal had settled. Ullaskar found a job as a teacher in a school for refugee children. He would look after Leela till she passed away a few years later. After her death, Ullaskar would move back to spend time at his old Anushilan Samiti akhada where he died, almost forgotten, in May 1965.