The Chapati Movement: A Silent Warning Passed From Hand to Hand

-Hemangi maheshwari

There are revolts that announce themselves with fire, with slogans, and the roar of a charging crowd. And then, there are others that move quietly, like whispers in the dark, passed hand to hand like secrets too dangerous to speak aloud. In the early months of 1857, as India stood on the edge of a revolt that would shake the British Empire to its core, a strange and silent phenomenon swept across villages and towns, one that didn’t use weapons, but chapatis. Yes, plain, round Indian bread. Delivered from village to village without explanation, without a word spoken. Thousands of them. No pamphlets, no manifestos, just an eerie sense of urgency and something unmistakably imminent.

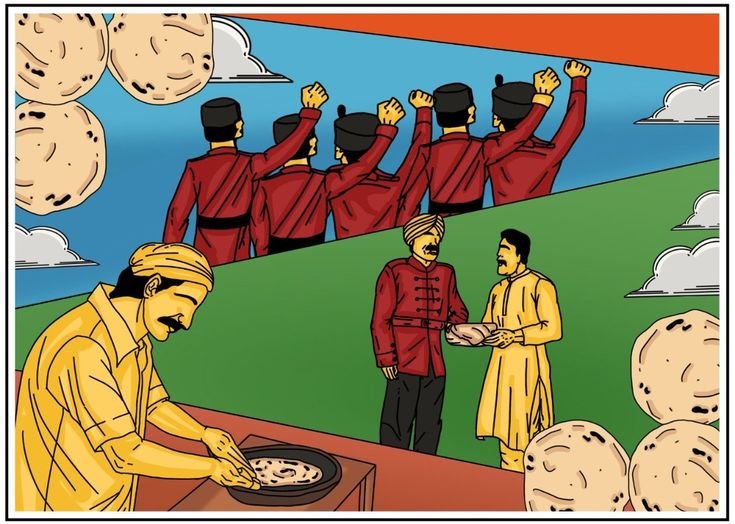

It began subtly enough, so subtly that at first even the British weren’t sure what to make of it. A runner would appear in a village and hand over a bundle of chapatis to the local watchman. No instructions, no message, only an expectation: send more chapatis to the next village, immediately. The watchman, confused but strangely compelled, would comply. And just like that, the chapatis began to travel, across hundreds of miles, cutting through caste and community, untouched by religion, disregarding language. In a land often divided by identity, the chapatis united people in silence. No one quite knew what it meant, but everyone understood that it meant something.

British officers stationed across North India were baffled. Reports of chapatis being distributed in large numbers flooded in from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and parts of Maharashtra. The numbers were staggering. In one report, nearly 90,000 chapatis were believed to be moving across just one region in a matter of days. It wasn’t just the scale, it was the coordination. At a time when there were no telephones, no modern transport, how did this strange system of delivery work with such terrifying precision?

Even more puzzling was the reaction of the villagers. When questioned, most of them didn’t offer resistance, but neither did they explain anything. It was almost as if they were in on a shared understanding, bound by something wordless. Some said the chapatis were meant to ward off a coming plague, others whispered about the arrival of a great storm, or the brewing of war. But no one would say more. And perhaps they didn’t need to. The unease, the electric sense of a gathering storm, was enough. The silence itself spoke volumes.

It’s hard to trace where the first chapati came from, or even who thought of it. Some historians speculate it was a symbolic act, a reminder of unity, of food as sustenance, of circles that bind and hold. Others think it was a code, a secret signal passed among revolutionaries who were planning something bigger, something explosive. And indeed, just a few weeks later, the First War of Independence , what the British called the Sepoy Mutiny, erupted in May 1857. The chapatis, some believe, were a psychological build-up, a rehearsal of mass coordination, a test of how fast something could spread without the Empire noticing until it was too late.

The British, for all their military might, were deeply unsettled. In their private writings, officers often sounded more anxious about the chapati movement than even armed resistance. It represented something they couldn’t quite control, the hearts and minds of ordinary Indians, the mysterious ways in which they communicated, the power of symbolism over speech. To them, the chapatis weren’t just bread. They were a warning. And worse , they were a warning the British couldn’t decipher.

But what makes the chapati movement so compelling isn’t just its historical enigma. It’s the way it reflects India’s long-standing tradition of resistance through subversion. The chapatis didn’t call for violence, but they mobilized an entire population. In a colonized country where every expression of dissent was watched and punished, this silent circulation was perhaps the most radical act possible. It was, in a way, civil disobedience before the term was even coined.

Imagine it: the hands that rolled the dough, pressed it into shape, and baked it on firewood were not those of soldiers or kings, but of farmers, mothers, travellers, priests, and potters. Each one passing it forward without fully knowing why, but knowing it must be done. The power of that, of a nation stirred into quiet urgency, is hard to ignore.

Of course, modern historians still debate its true meaning. Some argue it was a coincidence , a folk ritual misinterpreted, or a logistical effort tied to upcoming fairs or religious festivals. There are even suggestions that it was nothing more than a rumor that snowballed. But those arguments, logical as they may sound, often fail to account for the sheer scale of the phenomenon, and more importantly, its timing.

Because sometimes, the meaning of a movement is not found in records or reports, but in its impact. The chapatis didn’t start the revolt of 1857, but they stirred something beneath the surface, something that was already alive but waiting for a sign. The chapatis were that sign. And for a brief moment, in kitchens and fields, across temples and chowks, India listened.

Today, when we look back at the events of 1857, we remember the bloodshed, the betrayals, the fierce battles and fallen cities. But tucked away in the margins is the story of bread, not as food, but as a signal. A movement so understated, so quiet, and yet so widespread, it defies categorization. It’s not remembered with statues or ceremonies. There are no public holidays for it. But it remains one of the most hauntingly beautiful reminders that revolutions don’t always need speeches or swords. Sometimes, they begin with something as ordinary, and as powerful , as a chapati.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s why it worked. Because it didn’t call attention to itself. It didn’t announce rebellion. It passed silently, like a warning in the wind, a heartbeat just under the surface. And by the time the empire noticed, it was already too late.