Hollywood vs. History: When Cinema Twisted the Past for the Plot

→ Explore the debates around historical inaccuracies in films like Braveheart, The Patriot, or Pearl Harbor.

-Anushka Sengupta

“Hollywood vs. History: When Cinema Twisted the Past for the Plot”

→ Explore the debates around historical inaccuracies in films like Braveheart, The Patriot, or Pearl Harbor.

Introduction

Cinema has an extraordinary capacity to animate history—recreating wars, dramatizing revolutions and makes the long lost past feel magically vibrant. Hollywood, particularly, seems to have mastered the historical epic. But, with that power comes a distorted version of reality. Braveheart (1995), The Patriot (2000) and Pearl Harbor (2001), are great spectacles but critically assessed for manipulating historical facts.

This essay will outline how Hollywood changes relevant historical events for dramatic narrative, nationalist purposes and emotional impact. Artistic license is a cornerstone of film-making, but modified events, when repeated and deliberate distortions of the past, have real impacts on collective memory and historical knoledge. A critical assessment of the films mentioned will examine at what point the storytelling wins over actual history.

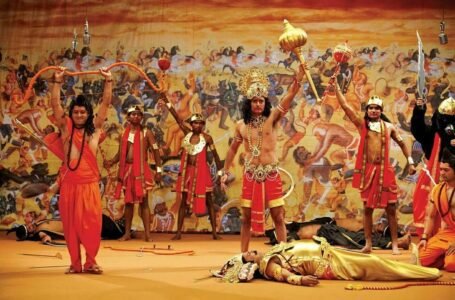

Braveheart (1995): Myths Around a Scottish Icon.

Mel Gibson’s Braveheart is an Oscar-winning historical epic that popularized the story of William Wallace, Scotland’s freedom fighter and inspired a global interest in Scotland’s past, despite historians highlighting the numerous inaccuracies it presented. The film depicts Wallace leading the rebellion shortly after the supposed death of his wife, but the historical William Wallace had launched its campaign years later, and there is absolutely no indication he was originally inspired by any romantic tragedy. There is the highly controversial suggestion of prima noctis in the film – that English lords used to sleep with Scottish brides on their wedding night. There is no historical evidence that this ever truly existed in medieval Scotland. Wallace and his soldiers wear kilts and paint their faces blue (like Picts), even though kilts wear not worn for at least 300 years later and blue face paint dates back to Roman times, long before Wallace’s time. The film depicts Bruce as someone who betrays Wallace, only to redeem himself later in the film. Historians argue that Bruce was more politically cautious than treacherous, and there is not record of him betraying Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk. Braveheart’s historical distortions are used to dramatize the story. Wallace is presented as a Christ-like martyr rebelling against oppression and betrayal. The historical deviations create a clear moral binary for audiences to understand good against evil while flattening the realities of 13th century Scottish politics.

The Patriot (2000): American Heroism and Historical Amnesia

Roland Emmerich’s The Patriot features Mel Gibson as Benjamin Martin, a composite character based loosely on some real figures including one of the most famous, Francis Marion, also known as the “Swamp Fox”. The film depicts the American Revolutionary War- tells a story filled with emotion, but offers its audience with revisionist history. For instance, the film has British soldiers locking civilians into a church and burning them alive – a crime that historians believe did not happen during the American Revolutionary War. The critics also say that this scene is just like the Nazi crimes and is an inappropriate transplantation of 20th century crimes against humanity to the conflicts of the 18th century. The British villain Colonel William Tavington (inspired by Banastre Tarleton) is characterized as a war criminal, ruthless in his brutality. Though Tarleton was aggressive during battles, he did not commit genocide. Benjamin Martin is presented to audiences as a moral family man whose family has been victimized by the British. However, some historians point out that Francis Marion, on whom Martin is based, was a slaveowner who committed vicious campaigns against Native Americans. Despite this problematic legacy, the film ignores the facts in depicting Martin freeing enslaved people and siding with the concept of racial equality – reflecting contemporary liberalism rather than providing historical accuracy. The distortions in The Patriot serve a purpose- to incite American patriotism and represent the Revolution as a morally black-and-white conflict. For cinematic convenience, the truths of divided loyalties, wartime violence on all sides and the ambivalence towards the limitations of early American ideals must be muted.

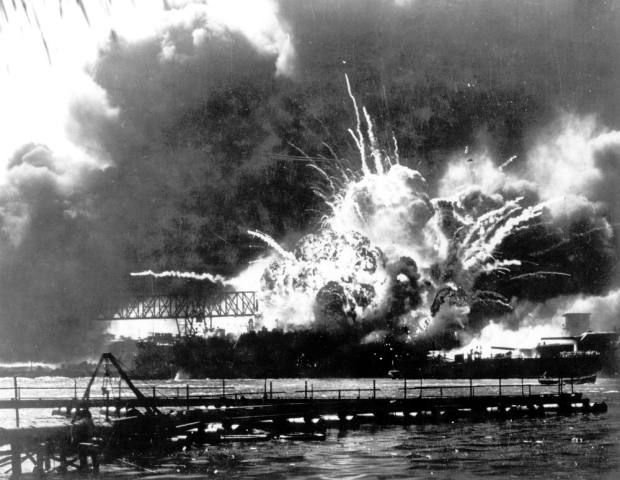

Pearl Harbor (2001): Romantic Fiction over Real History

Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor (2001) takes an important moment in American history and recreates it as the backdrop for a love triangle. While the film is visually stimulating with dramatic moments, it has rightly been criticized because it is riddled with historical inaccuracies. The primary plot is a fictional love triangle involving two pilots and the nurse they are connected to, which distracts from the real tragedy and heroism involved in the event of December 7, 1941. Though the actual Doolittle Raid is referenced (the American counterattack against Japan), but fictionalized protagonists are credited, which takes away the efforts from those actual warriors’ deeds. The Japanese are portrayed as ruthless aggressors with limited context about the strategic motivations behind it, reducing complexity and global political tensions to uncomplicated villainy. The film implies that U.S. intelligence had no awareness about the attack, when in fact there were major intelligence failures and serious ignored warnings. While Pearl Harbor offers impressive re-creations of the bombing, the act itself becomes a dramatic set-piece rather than becoming a centre-point of reflection on a tragedy. Survivors of the attack and historians have criticized the film for oversimplifying and minimizing the anger, confusion, heroism and disillusionment associated with that day.

Narrative and Emotional Resolution

The audiences want compelling stories. Historical events are often complex, ambiguous and slow to develop and historians usually complain that Hollywood does not follow “events” that really stand in the way of forming a convenient narrative that has a beginning, middle and end- psychological-emotional arc, and ultimately character motivation that can make a story profitable.

Cultural Politics and Nationalism

Historical films are not ideologically neutral. For instance, Braveheart glorifies Scottish nationalism as a virtue, and The Patriot promotes American reaction to tyranny as a virtue. Even Pearl Harbor reinforces bravery in the U.S. military. Again, these films create and represent national identities, sacrificing nuance for affirmation, but at least for intended effects, it is virtue.

Box office almost always outweigh historical truths. Producers and studios are responding to the market for mass appeal. In terms of financial viability, producers and studios simply like it when their films can make money globally, where simple, emotional and dramatic stories are easier to share compared to nuanced, culture-laden, specific truths. When the history of the film is concerned, for many more or less, the screen is the only source of explanation. When the fictionalized story becomes more memorable than scholarly accounts, it rewrites public memory. But by concentrating on made-up characters or fictitious outrages, films can sideline genuine individuals who made key contributions. Thousands of nurses, soldiers and officers are lost in the haze of fictional love interest in Pearl Harbor. Teachers and historians are left, as seems forever to be the case, cleaning up after popular movies. Therein lies the tension between pop culture and academic history.

Conclusion

While historical films such as Braveheart, The Patriot and Pearl Harbor are visually stunning spectacles that captivate our emotions, they can only do so by distorting the past. These films present myths as history. While we might think of the historical film genre as a harmless, trivial choice of entertainment , it has the power to illuminate history—but, alternatively, it can also obscure it, especially when drama takes the place of documentation. Instead of demanding absolute historical authenticity from every frame of the film, consumers should be able to participate as critical viewers of historical films, understanding that they are interpretations and not historical records. Historical films may twist history to serve the plot; however, audiences can untwist it through awareness, education and a healthy skepticism of spectacle.