Mesopotamian Civilization and Its Art: A Glimpse into the Cradle of Creativity

Mesopotamian civilization, often referred to as the “cradle of civilization,” emerged in the fertile plains between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. It spanned over several millennia and gave rise to some of the most influential art forms in human history. The art of Mesopotamia is a reflection of the civilization’s intricate social, political, and religious dynamics. As various empires and city-states rose and fell, each left behind a unique artistic legacy that contributed to the cultural tapestry of the ancient world.

Major civilisation

Sumerians

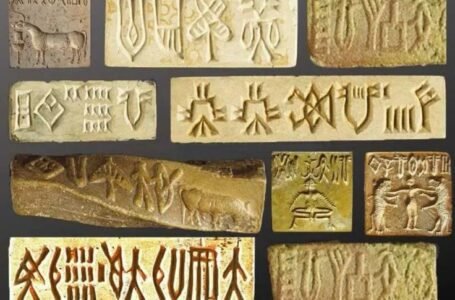

The earliest period of Mesopotamian art is associated with the Sumerians, the creators of the first known form of writing and complex urban societies. The Sumerian city-states, including Ur, Lagash, and Uruk, were built around massive temple complexes dedicated to gods and goddesses, marking the first significant influence of religion on art. The Sumerians believed that the gods were directly involved in the affairs of their city-states, and their art often reflected this divine connection.

Ziggurats and Religious Art

At the heart of every Sumerian city-state was a ziggurat, a massive stepped pyramid-like structure made of mud brick, rising above the flat landscape. These ziggurats were symbolic mountains, believed to connect the earthly realm with the heavens. They served as temples and as centres for religious and administrative activities. The most famous ziggurat, the Ziggurat of Ur, was dedicated to the moon god Nanna. These architectural wonders were often adorned with reliefs and sculptures depicting the gods, rulers, and scenes of rituals.

The votive statues of Sumer, such as those found in the Tell Asmar Hoard, are among the most iconic Sumerian artworks. These statues, often made from alabaster, limestone, or gypsum, feature wide eyes and clasped hands, symbolising perpetual prayer and devotion to the gods. The Sumerians used these statues as stand-ins for themselves during religious ceremonies, embodying their desire for divine favour and protection.

Decorative Arts and Mosaics

Sumerian decorative arts were intricate and often served both religious and social functions. Mosaics from the Royal Tombs of Ur, like the Standard of Ur, depict scenes of both war and peace, demonstrating the Sumerians’ complex social and political life. The mosaic features two panels, one showing a king leading his troops to battle and the other displaying a lavish banquet scene. The vivid use of lapis lazuli, shell, and red limestone in the mosaics highlights the Sumerians’ skill in crafting and their ability to represent complex narratives.

Akkadian Empire

The rise of the Akkadian Empire marked a shift in the artistic traditions of Mesopotamia. Under Sargon of Akkad and his successors, the art of the Akkadian Empire began to focus on the glorification of the king as a divine ruler and conqueror.

Royal Portraits

The Akkadians were pioneers in creating more naturalistic and individualised royal portraits. The Head of Sargon, made of copper, exemplifies this shift toward realism. The face, though stylised, reflects an attempt to capture a sense of personality and authority, showcasing the importance of the ruler in Akkadian society. Another iconic piece from this period is the Stele of Naram-Sin, which depicts the king’s military triumphs. The king is shown in a hierarchical scale, much larger than his soldiers, emphasising his divine status and heroic qualities. This form of royal propaganda was designed to reinforce the king’s power and divine right to rule.

Monumental Reliefs

The Akkadians also created monumental stone reliefs to commemorate military victories and royal decrees. These reliefs, such as the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, illustrate the Akkadian mastery of both art and propaganda. They combine complex narrative elements with the depiction of military strength, enhancing the king’s image as both a divine and earthly ruler.

Neo-Sumerian Period

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, Sumerian culture was revived during the Neo-Sumerian period. The most notable ruler of this era was Gudea, the king of Lagash, who promoted a resurgence of Sumerian religious and artistic traditions.

Gudea’s Sculptures

The sculptures of Gudea are perhaps the most significant artistic achievements of this period. His many statues, made from hard stones like diorite, portray the king in serene and dignified poses. The Seated Gudea, for example, shows the king sitting cross-legged with his hands folded in prayer. His strong, compact form and serene expression communicate both his power and piety. The proportions of the statue, although slightly stylised, convey a sense of idealised strength and divine favour. These statues were intended to emphasise Gudea’s role as both a religious leader and a ruler who maintained the welfare of his people.

Temples and Architecture

In addition to sculpture, the Neo-Sumerian period saw the construction of impressive temples and other public buildings. Gudea was particularly known for his building projects, including the restoration of ziggurats and the construction of new temples dedicated to the gods. The artwork in these temples often depicted the king in divine or semi-divine contexts, reinforcing his role as the intermediary between the gods and his people.

Babylonian Period

The Babylonian Empire rose to power under Hammurabi in the 18th century BCE, and its art focused heavily on law, order, and divine kingship.

The Code of Hammurabi

The most famous piece of Babylonian art is the Code of Hammurabi, a stele that contains a compilation of laws inscribed on it. At the top of the stele, Hammurabi is depicted receiving the laws from Shamash, the sun god, symbolising the divine legitimacy of his rule. The reliefs on the stele are carefully detailed, showing the king and the god in a hierarchical scale, with the king appearing smaller than Shamash, emphasising the divine authority behind the law. The stele not only records legal codes but also serves as a symbol of the king’s role as the enforcer of justice.

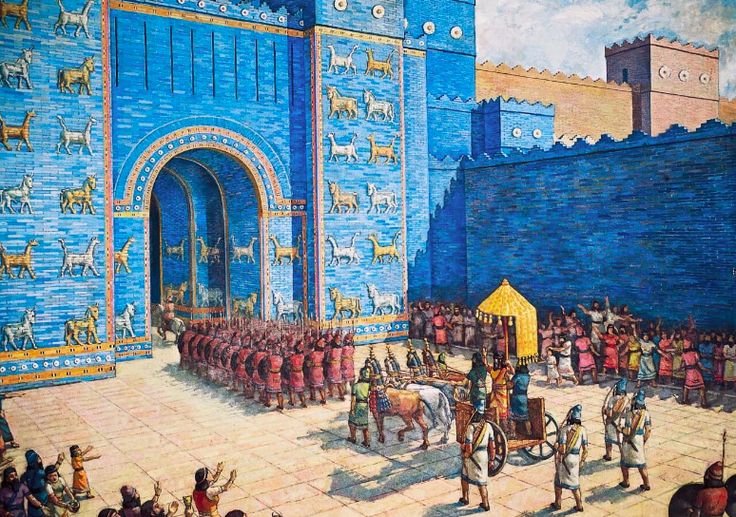

Babylonian Architecture and the Ishtar Gate

The Ishtar Gate, constructed by Nebuchadnezzar II, is another remarkable example of Babylonian art and architecture. This gate, made of glazed bricks and adorned with images of bulls, dragons, and lions, was part of the processional route that led into the city of Babylon. The gate’s vivid blue tiles, combined with the sculpted creatures, symbolise the power and majesty of the Babylonian gods, especially the goddess Ishtar. The Ishtar Gate is a striking example of how Babylonian rulers used art and architecture to celebrate their deities and reinforce their political dominance.

The Assyrian Empire

The Assyrian Empire was one of the most powerful empires in the ancient Near East, and its art was closely intertwined with the empire’s military conquests, political authority, and religious beliefs. Art and visual culture were used to propagate royal power, commemorate military victories, and reinforce the king’s divine right to rule. The Assyrian kings saw themselves as both warriors and protectors of their people, and this dual identity is reflected in the art produced during their reign.

Assyrian Relief Sculptures:

One of the most significant forms of Assyrian art was relief sculpture, often found in the palaces of Assyrian kings. These sculptures were not merely decorative but were used to tell the stories of royal triumphs, military victories, and divine protection, thus promoting the king’s authority and divine favour.

The Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal is perhaps the most iconic of these reliefs. It depicts King Ashurbanipal, one of the last great Assyrian kings, hunting lions in a ceremonial manner. Lions were symbolic of royal power, bravery, and control over nature, and their hunting was a metaphor for the king’s strength and control over the natural and political world. The reliefs portray Ashurbanipal as a brave and skilled hunter, slaying lions with ease, showcasing his valour and prowess. In these scenes, the king is often shown standing, bow in hand, or seated in a chariot, directing his archers. The lions, which are depicted in motion, show a dynamic action, emphasising their power and the king’s challenge in overcoming them. The composition of these reliefs is carefully designed to depict both the majesty of the king and the nobility of the hunt, which was an activity that symbolised the king’s divine mandate to protect and defend his realm.

Winged Genies:

Assyrian art also included the portrayal of winged genies, or human-headed winged figures, which were used as protective symbols, especially in the royal palaces. These figures were often depicted with the bodies of human men and the heads of bearded individuals, with large wings extending from their shoulders. They were believed to possess powerful, supernatural abilities and were seen as intermediaries between the divine and earthly realms.

Winged genies were often placed at the entrances of palaces and temples as protective figures, intended to guard against evil forces and ensure the safety of the king and his empire. The figures were portrayed in a stately, upright posture, and sometimes they were depicted holding a sacred cone or a mace, symbols of authority and divine protection.

Assyrian Military Art:

their art was often used to commemorate their military campaigns and conquests. Reliefs depicting sieges, battle scenes, and the king’s triumphs were common. The siege of Lachish reliefs, which are housed in the British Museum, for example, depict the Assyrians as they besiege the city of Lachish in Judah, showing the military tactics and brutal methods employed by the Assyrians to subdue their enemies. In these scenes, Assyrian soldiers are depicted in great detail, showing their weapons, armour, and military strategies, while the defeated enemies are shown in various states of submission, their fate often sealed by the king’s orders

Conclusion

Mesopotamian art is a rich tapestry that reflects the culture’s deep connection to religion, politics, and social structures. From the religious devotion embodied in Sumerian ziggurats to the royal glorification seen in Akkadian and Assyrian art, each period in Mesopotamian history contributed unique and profound artistic traditions. These artworks not only serve as historical records but also as windows into the values, beliefs, and power structures that shaped one of the world’s first great civilisations.