Göbekli Tepe: The Unveiled Cradle of Civilization

Among few discoveries, that have been as fascinating, controversial, and debated within the humongous expanse of human history, is Göbekli Tepe – a sensational archaeological site in the southeast of Turkey, which has already christened itself as the oldest-known temple complex worldwide. Göbekli Tepe has thrown into question the traditional wisdom regarding the evolution of civilization after all, because hunter-gatherers built it more than 11,000 years ago, or nearly at a time when Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids of Egypt were not yet erected. All that has been thought about the origins of religion, civilization, and monumental construction has been turned upside down by finds from Göbekli Tepe, forcing experts into a rethinking of the story of human progress.

It is impossible to overemphasize the importance of Göbekli Tepe. There can be caught a glimpse of what human history was at that moment when small, nomadic communities were on the threshold of becoming stable society with superior social constructs, agriculture, and spiritual beliefs. This site, besides displaying the skills of the builders in a high state of development, also raises the possibility that, before agriculture, the demands for extensive buildings could have been driven by the demands for community and religious purposes. Göbekli Tepe continues to attract academic interest from all corners of the globe as further excavations unearth more strata of history that may fully rewrite the textbooks.

History

Göbekli Tepe is Turkish for “Potbelly Hill”. It was discovered first in 1963 as part of a survey for the Universities of Chicago and Istanbul. At the time, it was not understood just what this place was, and it was therefore thought to be little more than a Neolithic hilltop settlement. Indeed, German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt did not realize the actual significance of the site until he returned there mid-1990s. Being deeply passionate about the early Neolithic societies he was concerned with, Schmidt very quickly discovered that the limestone pillars within Göbekli Tepe are not a mere ruin of an ancient village but an incredible complex of temples from the prehistoric period.

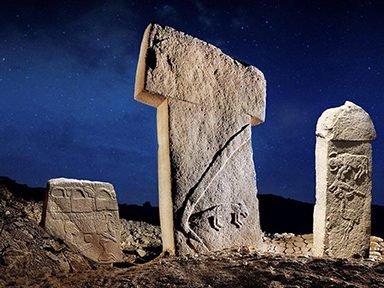

The Göbekli Tepe’s pillars appear in oval and circular configurations; some stand up to 16 feet tall and weigh up to 20 tons. They are decorated with intricately carved images of humans and animals and abstract symbols-most of which have no equivalent anywhere else in Neolithic sites. Using radiocarbon dating, the oldest parts of Göbekli Tepe date from about 9600 BCE, at a time when hunter-gatherer societies still dominated most human populations. It is particularly remarkable because it suggests planned large-scale construction was conceivable even before settled agricultural communities existed.

The old established wisdom before Göbekli Tepe was discovered was that the Neolithic Revolution-the shift from nomadic to agricultural and permanent settlements- was the direct cause of development into sophisticated societies capable of constructing monumental architecture. Göbekli Tepe, however, blows this concept right to smithereens. The website raises the possibility that the desire to establish sacrosanct, communal areas may have preceded rather than followed the growth of agriculture. In short, it was perhaps the need for halls for social and religious gatherings that led early people to begin settling and eventually culminated in the domestication of plants and animals.

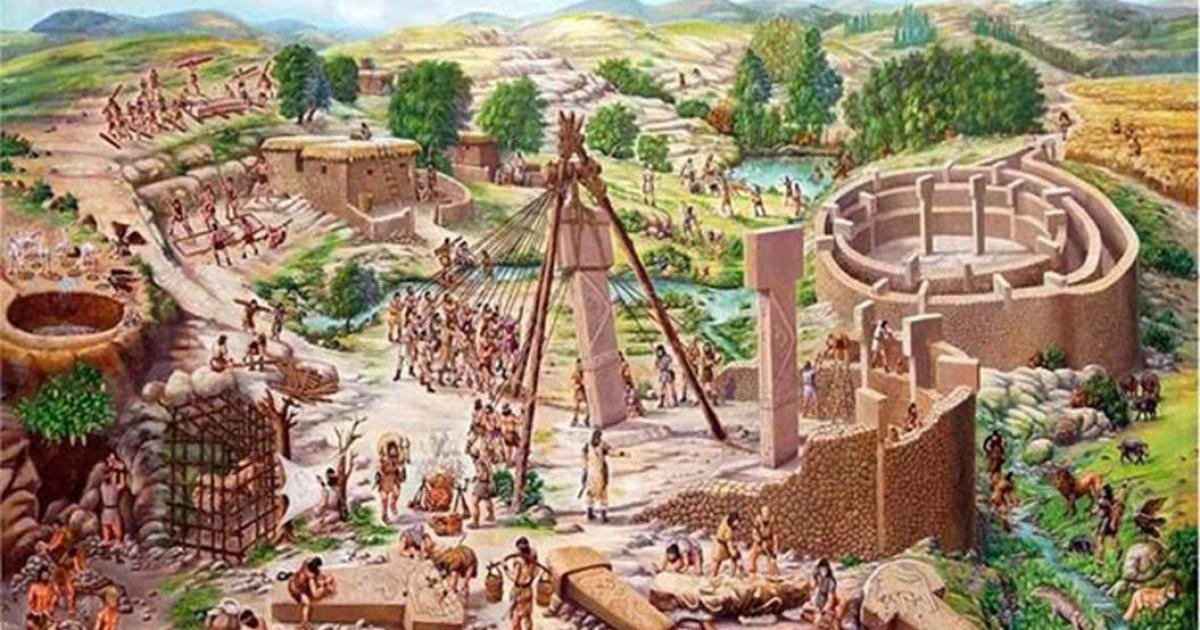

Göbekli Tepe’s discovery has caused historians and archaeologists to passionately argue. Other theorists suggest that the construction was a “Neolithic Cathedral” built and developed by a number of hunter-gatherer communities that came together for rituals and ceremonies. It is even argued that it may have become the center of a network of pilgrimages where people in common religious rituals from all parts of the region came together. The monumental nature of Göbekli Tepe demanded a level of coordination and organization that was imaginable for the pre-agricultural society.

Journey

The learning of Göbekli Tepe has proven to be a laborious and lengthy process. Sitting atop a barren, windswept hill overlooking the Harran Plain, an area where human activity has crossed paths for thousands of years, the site itself dates back to a time when some of its secrets may be beyond our comprehension. All this rubble and debris covered the entire area; many of them were placed there, seemingly deliberately, by the prehistoric builders who had buried the place thousands of years ago. Still, whatever its twisted history and whatever its importance, a new layer of dirt dug up always yields a revelation.

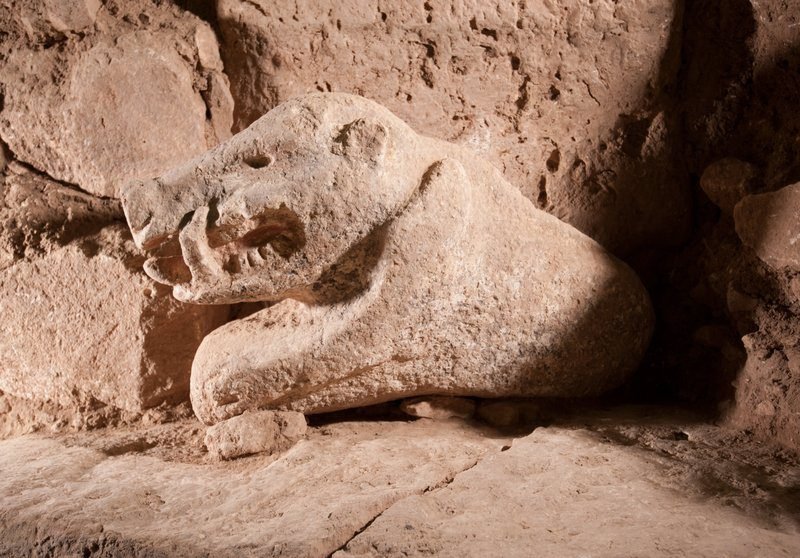

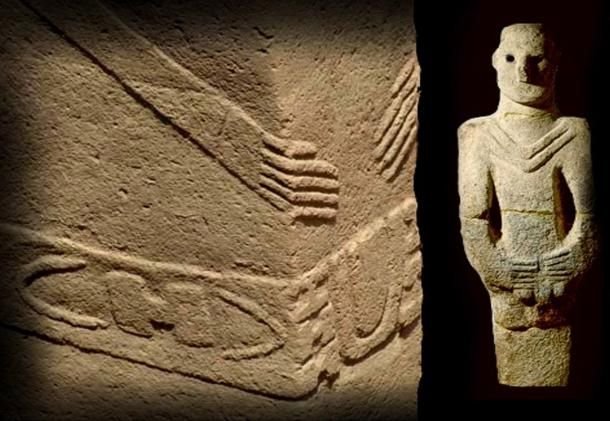

One of the most striking features about Göbekli Tepe is the arrangement of its stone pillars into circular enclosures. Also referred to as “sanctuaries” or “temples,” these enclosures are a series of larger center pillars surrounded by smaller periphery pillars. Many of the center pillars have the greatest ornamentation, often in the form of reliefs of lions, bulls, foxes, snakes, and birds. It is considered that those who created the structure placed a heavy symbolic meaning in these carvings rather than simply using them as decoration. A number of the pillars also contain abstract symbols that can be identified as stylized representations of humans or gods, such as the T-headed form that crowns a number of the pillars or the H-symbol.

The often winding layout of the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe, which they connect through narrow tunnels, may therefore have been designed to limit the free movement of human beings within the site. This would mean that some areas were inaccessible to the public, likely reserved for priests or other influential people who led various ceremonies and rituals. Some enclosures contain stone seats around its periphery, which suggests these areas were public assembly grounds where people would sit and observe the ceremonial activities being performed in the center of the enclosure.

The site grows in complexity as newer cages were superimposed over older ones. The largest enclosures and also the oldest enclosures date back to the 10th millennium BCE, but these are the most decorated. Simple and smaller enclosures made of later materials may be a sign of a phase shift or even abandon the site due to the decrease of its significance. Interestingly, perhaps for mysterious reasons, the whole complex was intentionally buried circa 8000 BCE. The burial surprisingly well-preserved the edifices remarkably well so that they remained intact for millennia until their discovery in the 20th century.

Besides the actual excavation of Göbekli Tepe, not all efforts have been in its discovery quest. It has also forced reconsideration of several assumptions about the origin of human society. The popularity surrounding the wisdom over the Neolithic Revolution concerning the origin of civilization goes in contradiction with the notion that large, organized communities may exist even before the introduction of agriculture. Open up the possibility that advances on that level of social behavior, such as religion, teamwork, and creative expression, date back much farther than anyone thought it did: Göbekli Tepe opens up.

Archaeology’s most ambitious task over the last century has been to find Göbekli Tepe. The team of the archaeologists, who have been digging at the site first under Klaus Schmidt and then after his death, under his successors, discovered a number of paradigm-shifting finds that have very radically changed our understanding of human prehistory. Uncovered inch by careful inch, Göbekli Tepe has been telling its secrets step by step from each stratum of earth, which told more about this complex of construction, utilization, and abandonment.

The scale at which Göbekli Tepe sits is perhaps one of the most fascinating aspects of the site. The bulk of this complex remains buried under ground; so far, only 5% of the site has been excavated. The exposed areas are loaded with many circular enclosures replete with several large stone pillars arranged in an oval or circular inside of them. These pillars, some 20 tons in weight, were brought to the site using simple equipment and simple techniques from local sources of limestone. Labor-intensive, the carving and construction of these pillars give testimony that the Göbekli Tepe builder belongs to a considerable well-organized community.

Among the greatest enigmas of the elaborate features of Göbekli Tepe are the engravings on the pillars. Many of the animals represented on the reliefs as snakes, scorpions, wild boars, cranes, and foxes must have been only symbolic or totemic representations rather than realistic illustrations of what was the local fauna. All these animals are present in the art of Göbekli Tepe, which implies that their creators held them in awe and probably treated them as gods, spirits, or other supernatural entities. As their meanings are still generally unknown, the stylized human forms and abstract symbols also found on many of the pillars increase the enigma.

Excavations at Göbekli Tepe have revealed a wealth of other objects besides the enclosures and the pillars, including flint tools, pieces of bone, and scoured stones. In fact, these artifacts give a glimpse of the people involved in constructing and using the site. For instance, the emergence of flint tools indicates that those makers of the structure were skilled craftsmen who had etched the fine designs on the pillars with such tools. Animals accounted for an important proportion of the diet, and may even have served as actors in Göbekli Tepe rituals themselves. This is merely speculation, given the many bone parts found at the site.

Göbekli Tepe is also characterized by intentional burial. It was completely buried with huge masses of earth and rubble around 8000 BCE, thus saving it from human destruction for several thousand years. The authors of the publication are still arguing about the aim of such burial. According to some researchers, new cults’ mere appearance, which eventually changed religious rituals, could have been the reason those people who erected it felt compelled to leave it and bury it.

Conclusion

Göbekli Tepe defies long held beliefs about the beginnings of civilization and is a great testament to the ingenuity and spirituality of our prehistoric predecessors. Because of the massive pillars and elaborate sculptures in this ancient temple complex, large-scale building projects and organized religion predate agriculture and settled populations. The deliberate burial of Göbekli Tepe in 8000 BCE also seems to create an air of mystique around it, as this suggests a certain shift in culture or spirituality that precipitated such an abandonment. Göbekli Tepe offers one of the most fascinating glimpses into the early pages of human history as archaeologists continue to uncover the mysteries surrounding the site, reminding us of how much more deeply the foundations of human civilization and society reach than we initially assumed. The location throws light not only on our view of the past but also on the universal human aspiration for common areas, a long-term legacy, and a connection with the holy. Göbekli Tepe is, therefore, an artifact of history, but more than that: it is a living sign of humanity’s relentless quest to define meaningful and communal lives in an ever-changing world.