Jack the Ripper: History, Myth, and the Anatomy of an Unsolved Crime

-Prachurya Ghosh

Introduction: The First Modern Serial Killer

Few criminal cases in modern history have generated as much fascination, fear, and speculation as the murders attributed to Jack the Ripper. Active in the impoverished districts of London in 1888, the Ripper is widely regarded as the first “modern” serial killer—an anonymous figure whose crimes were not only brutal but also intensely mediated through newspapers, letters, and public imagination. Unlike earlier murderers, whose actions were treated as isolated events, the Ripper emerged as a continuous presence in public discourse, a shadowy personality constructed collectively by journalists, police reports, rumors, and popular fear.

The Ripper case occupies a unique position at the intersection of crime, urban history, media studies, and social psychology. It is not merely about a sequence of murders; it is about Victorian society itself. The case exposes deep anxieties about poverty, gender relations, urban anonymity, and the limits of modern institutions. The fact that the killer was never identified transformed the Ripper into a symbol rather than a person—a symbol of unresolved violence and the dark side of modernity. Even today, more than a century later, the Ripper continues to attract scholars, writers, and conspiracy theorists, not because the mystery can realistically be solved, but because it reflects enduring cultural fears about crime and invisibility.

Victorian London and the World of Whitechapel

The murders occurred in Whitechapel, a district that represented the grim underside of Victorian progress. While Britain celebrated industrial prosperity, technological innovation, and imperial power, Whitechapel symbolized overcrowding, unemployment, alcoholism, prostitution, and homelessness. Thousands of people lived in common lodging houses where beds were rented by the hour. Families were packed into single rooms, sanitation was poor, and infectious diseases were widespread. Life expectancy in such neighborhoods was significantly lower than in wealthier areas of London.

Prostitution was especially visible in Whitechapel, not necessarily as a chosen profession but as a survival strategy for women with few economic options. Many women moved between casual sex work, domestic service, factory labor, and street begging. The boundaries between these activities were fluid, shaped by hunger and desperation rather than by identity. The women who became the Ripper’s victims were all associated with this marginal world. Their lives were marked by poverty, instability, alcoholism, and social invisibility.

Victorian attitudes toward class and morality shaped how these murders were interpreted. While newspapers sensationalized the crimes, there was also a tendency to blame the victims, portraying them as “fallen women” who had strayed from respectable life. This moral framing reduced public sympathy and contributed to weak institutional urgency in the early stages of the investigation. Violence against poor women was not treated with the same seriousness as violence against middle-class citizens. The Ripper case thus reveals not only a criminal mystery, but also a social hierarchy of whose lives mattered.

The Canonical Five: Victims of the Ripper

Although many murders were attributed to the Ripper at the time, historians generally agree on five “canonical” victims whose deaths share consistent patterns: Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. These women were murdered between August and November 1888, all in or near Whitechapel.

The similarities between these killings are striking. All occurred at night, in relatively isolated spaces. The victims were attacked quickly, suggesting that the killer relied on surprise and vulnerability rather than physical strength. The injuries focused on the throat and abdomen, indicating not random violence but symbolic targeting of the body. In the case of Mary Jane Kelly, the final victim, the attack occurred indoors and involved far more extensive mutilation, which many historians interpret as an escalation in the killer’s behavior.

These murders were not random street crimes. They followed a recognizable pattern: marginalized women, minimal witnesses, rapid execution, and symbolic bodily harm. This repetition is what distinguishes the Ripper from ordinary violence. It also enabled the police and the public to imagine a single author behind the crimes, transforming separate deaths into a coherent narrative of terror.

The Police and the Failure of Investigation

The investigation was primarily handled by the Metropolitan Police, assisted by the City of London Police. The most prominent officer involved was Frederick Abberline, a respected detective familiar with East London. Despite deploying significant manpower, the police were constrained by the technological and institutional limits of the time.

There was no fingerprinting system, no forensic databases, and no DNA analysis. Crime scenes were often contaminated by crowds of curious onlookers, journalists, and residents. Witnesses were unreliable, frequently intoxicated, frightened, or inconsistent. Street lighting was poor, patrol routes were limited, and communication between departments was inefficient. The police relied heavily on door-to-door questioning, informants, and patrols, but these methods produced little concrete evidence.

Public pressure increased dramatically after the killer began sending letters to newspapers, most notably the “Dear Boss” letter, which popularized the name “Jack the Ripper.” Although most historians believe these letters were hoaxes, they had a powerful cultural effect. They created the image of a taunting, intelligent criminal who enjoyed public attention and outwitted the authorities. The police were forced to operate under intense media scrutiny, which further complicated the investigation.

The Birth of the Ripper Myth

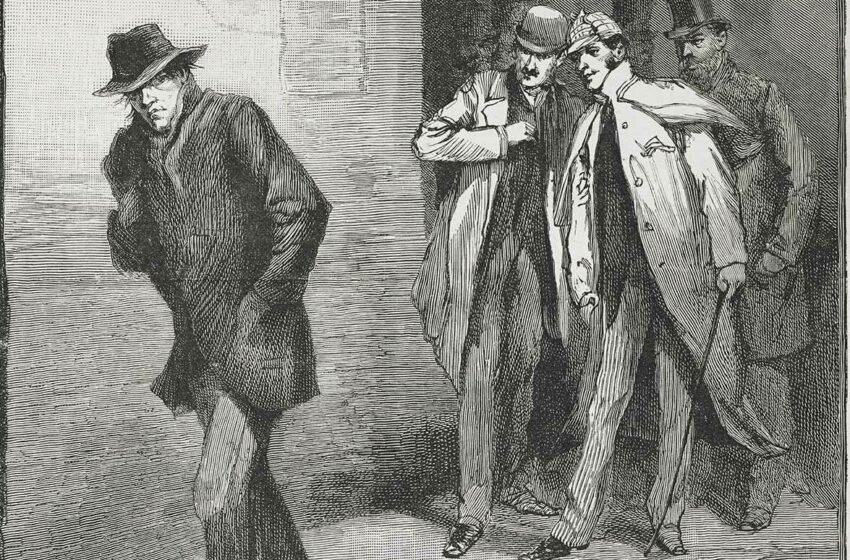

The figure of Jack the Ripper was shaped as much by journalism as by crime. Victorian newspapers competed fiercely for readership, and the Ripper murders offered sensational material: sex, violence, mystery, and fear. Graphic descriptions of the bodies, speculative psychological profiles, and dramatic illustrations filled newspaper pages. For the first time, a serial killer was treated as a public personality rather than an anonymous criminal.

This process created what modern criminologists call “celebrity criminality,” where the killer becomes more famous than the victims. The press transformed the Ripper into a theatrical figure—intelligent, elusive, almost artistic in his cruelty. In reality, the killer was likely an ordinary man who blended into the working-class environment of Whitechapel. But the myth portrayed him as a monstrous genius, reinforcing public fascination and fear.

The Ripper thus represents a turning point in the cultural history of crime. Violence was no longer just a local घटना; it became a serialized narrative consumed by mass audiences. The public followed the case like a story, waiting for new chapters, new clues, and new revelations. Crime became entertainment.

Medical Knowledge and the “Expert Killer” Theory

One of the most persistent interpretations of the Ripper is that he possessed medical or anatomical training. Contemporary doctors speculated that the precision of certain injuries suggested a surgeon, butcher, or medical student. This theory became deeply embedded in popular culture, reinforcing the image of a highly intelligent, professional killer.

However, modern historians and forensic analysts argue that this interpretation is overstated. The injuries, while severe, do not require advanced expertise. Basic anatomical knowledge—available to anyone working in slaughterhouses, meat markets, or even through observation—would have been sufficient. The idea of the “expert killer” reflects less about the actual evidence and more about Victorian anxieties toward science and medicine. At a time when scientific knowledge was rapidly expanding, there was a fear that modern expertise could be turned into tools of destruction.

Major Suspects and Competing Theories

Over the past century, more than a hundred suspects have been proposed. Among the most famous are Montague John Druitt, a barrister who died by suicide shortly after the murders; Aaron Kosminski, a Polish immigrant and asylum patient who lived in Whitechapel; and Walter Sickert, an artist accused in modern books.

Each theory offers a compelling narrative, but none are supported by definitive evidence. Royal conspiracy theories involving Prince Albert Victor or Freemasons are popular in fiction but lack historical credibility. Most serious scholars agree that the true identity of the Ripper is probably lost forever. The evidence is fragmentary, many police records were destroyed, and retrospective interpretations are shaped by confirmation bias.

Psychological Profile of the Ripper

From a modern criminological perspective, Jack the Ripper fits the profile of a sexually motivated, disorganized serial offender. His crimes targeted vulnerable victims, occurred impulsively, and lacked long-term planning. The violence appears expressive rather than instrumental, meaning it served to release psychological tension rather than achieve practical goals.

The killings were likely driven by deep emotional conflict related to sexuality, power, and control. However, any psychological diagnosis remains speculative. Without knowing the killer’s identity, it is impossible to determine his background, motives, or mental state with certainty. What can be said is that the pattern of violence reflects not just individual pathology, but also structural conditions that allowed such crimes to occur repeatedly without detection.

Why the Case Remains Unsolved

Several factors explain why the Ripper was never caught. Technological limitations prevented effective forensic analysis. Social invisibility meant the killer likely belonged to the same class as his victims and blended into the environment. Institutional bias led to low prioritization of crimes against poor women. Media interference distorted evidence through hoaxes and rumors. Finally, the loss and destruction of records eliminated many potential leads.

The Ripper case thus highlights how crime detection is shaped not only by investigative methods, but by social values, power structures, and institutional priorities. Justice is not merely a technical process; it is a social one.

Cultural Legacy and Popular Imagination

Jack the Ripper became a foundational figure in modern horror and detective fiction. He appears in countless novels, films, television series, comics, and video games. The Ripper established enduring cultural tropes: the anonymous serial killer, the urban nightmare, the obsessive detective, and the tension between rational investigation and irrational evil.

More importantly, the Ripper marks the moment when crime became mass entertainment. Murder was no longer consumed as isolated tragedy, but as serialized narrative. The public learned to follow crime as story, with characters, suspense, and unresolved endings.

Ethical Questions and Victim Memory

Modern scholarship increasingly questions the obsession with the killer rather than the victims. The women murdered in Whitechapel are often remembered only as components of a mystery, while the murderer is immortalized as a cultural icon. This raises serious ethical concerns. Does fascination with Jack the Ripper exploit real suffering? Does myth-making erase the structural violence experienced by marginalized women?

Some historians argue that the Ripper story should be reframed not as a detective puzzle, but as a history of poverty, gender violence, and institutional failure. The real lesson lies not in identifying the killer, but in understanding why such violence was possible in the first place.

Conclusion: The Ripper as a Mirror of Society

Jack the Ripper remains unsolved not only because of missing evidence, but because the case reflects deeper social realities. He was not a supernatural monster, but a product of Victorian London: its inequalities, its blind spots, and its moral contradictions. The true horror lies not in the mystery of his identity, but in the conditions that allowed such violence to occur repeatedly and to be transformed into spectacle.

In this sense, Jack the Ripper is less a person than a symbol—a symbol of how modern societies narrate violence, how victims are remembered or forgotten, and how fear becomes entertainment. The case endures because it forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about justice, memory, and the stories we choose to tell about crime.