The History of Print Culture: Knowledge, Power, and the Transformation of Society

-Prachurya Ghosh

Print culture refers to the complex system through which written texts are produced, circulated, consumed, and interpreted within society. It includes not only books and newspapers but also pamphlets, posters, journals, advertisements, and all other forms of printed material. The history of print culture is therefore not simply a technological story about the invention of machines, but a social history of how communication reshapes power, identity, and knowledge. The transition from oral and manuscript traditions to mass printing marked one of the most important turning points in human civilization, comparable to the development of writing itself.

Print fundamentally altered the way people experienced time, space, and authority. It created stable, repeatable texts that could travel across regions and generations, allowing ideas to circulate beyond local communities. Over time, print became a key force in the formation of modern institutions such as schools, churches, governments, markets, and nations.

Oral and Manuscript Traditions

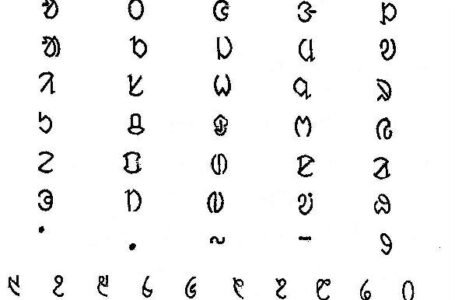

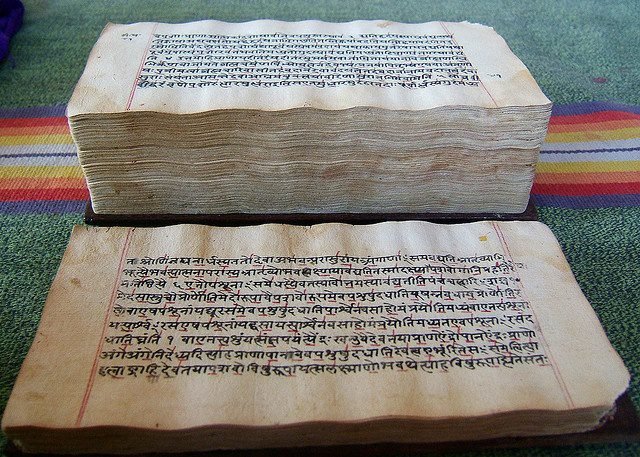

Before the rise of print, most societies relied heavily on oral communication. Knowledge was preserved through storytelling, memory, rituals, and public performance. Even when writing existed, literacy was limited to small elites such as priests, scribes, scholars, and administrators. Manuscripts were copied by hand, often in monasteries, royal courts, or specialized workshops.

Manuscript culture was slow, fragile, and expensive. Each copy required enormous labor, and errors were common. As a result, books were rare and highly valued objects. Reading was usually a collective activity, performed aloud in religious or educational settings. The authority of texts depended largely on tradition and institutional power rather than on widespread access.

This system limited the circulation of knowledge and reinforced social hierarchies. Control over writing meant control over history, law, and religious doctrine.

The Printing Revolution

The invention of the movable-type printing press in mid-fifteenth-century Europe, traditionally associated with Johannes Gutenberg, marked a revolutionary break from manuscript culture. For the first time, large numbers of identical texts could be produced quickly and relatively cheaply. This drastically reduced the cost of books and expanded the reading public.

The printing revolution did not immediately transform society, but over time its effects were profound. Print standardized spelling, grammar, and language. It stabilized texts, making it possible to refer to the same words and arguments across vast distances. This created the conditions for sustained intellectual debate, scientific collaboration, and political mobilization.

Print also shifted authority away from oral traditions and personal memory toward written evidence. What was printed increasingly came to be seen as more reliable, permanent, and legitimate.

Print and the Transformation of Knowledge

One of the most important consequences of print culture was the transformation of knowledge itself. In medieval Europe, knowledge was largely organized around religious theology and classical authorities. Print enabled the recovery and wide circulation of ancient Greek and Roman texts, contributing to the Renaissance.

Scientific knowledge also changed fundamentally. Scholars could now share experiments, diagrams, and observations across borders. The rise of printed scientific journals allowed knowledge to become cumulative, verifiable, and open to criticism. This laid the foundations of modern science and rational inquiry.

Print encouraged linear thinking, categorization, indexing, and referencing. Libraries expanded, encyclopedias were compiled, and education became increasingly text-based. Knowledge became something that could be archived, compared, and systematically improved.

Religion and the Crisis of Authority

Print played a central role in the transformation of religion. The Protestant Reformation is often described as the first mass media revolution. Martin Luther’s writings were printed in huge numbers and circulated across Europe within weeks. Religious debates that once remained within elite theological circles now reached ordinary people.

The translation of the Bible into vernacular languages allowed individuals to read religious texts directly, without priestly mediation. This weakened the authority of the Catholic Church and encouraged the idea of personal faith and interpretation. Religious identity became increasingly tied to reading and literacy.

Print thus contributed to the fragmentation of religious authority and the emergence of competing belief systems. It also intensified religious conflict, as different groups used print to attack rivals and promote doctrinal purity.

Print and the Emergence of the Public Sphere

Print culture helped create what political theorists call the public sphere, a space of discussion and debate outside direct state control. Newspapers, pamphlets, journals, and political essays enabled citizens to form opinions about social and political issues.

In early modern Europe, coffee houses and reading rooms became centers of political discussion, where printed materials were read aloud and debated. This new communicative space weakened traditional hierarchies and strengthened civic participation.

Print made it possible to imagine political communities beyond face-to-face interaction. People who had never met could share ideas, grievances, and identities through texts. This process was crucial in the development of modern democracy and civil society.

Print, Capitalism, and Nationalism

Print culture developed alongside the rise of capitalism. Printing became a commercial industry driven by markets, profit, and consumer demand. Publishers responded to popular tastes, producing novels, newspapers, magazines, and advertisements.

According to scholars like Benedict Anderson, print capitalism played a key role in the formation of nations. Newspapers and novels allowed people to imagine themselves as part of a shared community, even without direct contact. Print standardized national languages and spread common histories, myths, and symbols.

National identity thus emerged not only from political institutions but also from everyday reading practices.

Print in Colonial and Postcolonial Contexts

In colonial societies, print was both a tool of domination and resistance. Colonial governments used print to impose laws, bureaucratic systems, and cultural norms. Missionaries used print to spread religion and European values.

At the same time, colonized populations used print to articulate anti-colonial movements. Newspapers, journals, and political tracts became crucial instruments of nationalism. In India, for example, vernacular print helped create mass political awareness and unify diverse regions.

Print enabled new forms of collective identity that challenged imperial authority and contributed to the rise of modern nation-states.

Mass Literacy and Popular Culture

By the nineteenth century, industrial printing technologies made mass literacy possible. Cheap newspapers, serialized novels, school textbooks, and popular magazines transformed everyday life. Reading became a routine activity across social classes.

Print shaped modern popular culture, including fiction, romance, crime stories, and political satire. It also standardized education, created shared moral values, and promoted consumer culture through advertising.

The modern individual increasingly understood the world through texts, news reports, and printed representations of reality.

Print in the Digital Era

Although digital media has transformed communication, it has not eliminated print culture. Instead, digital technologies build upon earlier print-based habits such as reading, writing, archiving, and authorship.

The logic of print—linear text, citation, publication, and public debate—continues to structure online communication. Even social media operates through written language and textual identity.

The digital age can therefore be seen as a new phase in the long history of print culture rather than its end.

Conclusion

The history of print culture is the history of how societies learned to organize knowledge, authority, and identity through texts. Print reshaped religion, politics, science, and everyday life. It created the modern world by enabling mass communication, public debate, and collective imagination.

Far from being a neutral technology, print is a social force that transformed how humans think, remember, and govern themselves. Its legacy continues to shape contemporary society, even in an age dominated by digital media.