Rasputin and the Romanovs: Power Forged Through Faith

-Oishee Bose

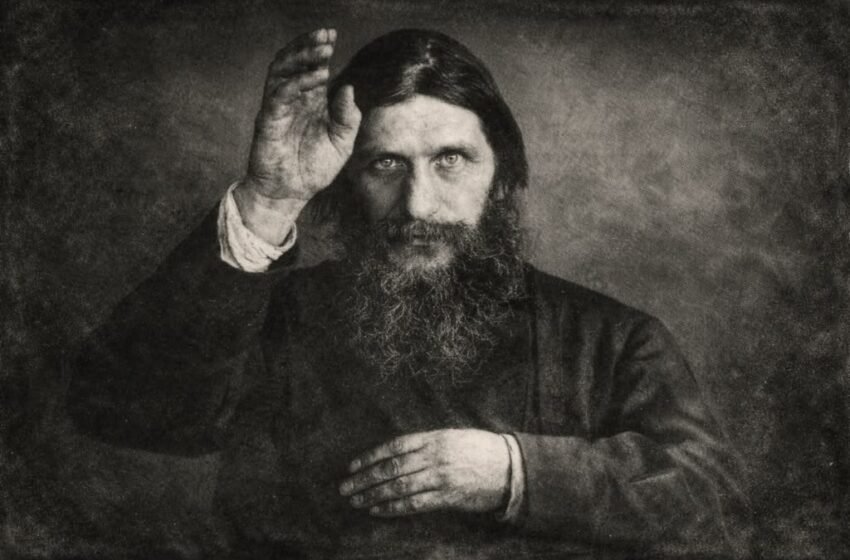

How did a rough Siberian peasant gain the trust of a mourning empress and grow into a man whose words could influence who entered and left governmental institutions? The answer is not in a lone theatrical moment or a secret plan. It rests in a gradual collection of fear, confidence, belief, speculation, and timing. Private despair started the connection between Grigori Rasputin and the Romanov family; it then developed inside a political structure already compromised by conflict, ambiguity, and solitude. Personal belief gained political relevance slowly. Uncertainty and fantasy turned out to be as potent as recorded events.

Pokrovskoye and the pilgrimage that changed him (1869–c.1897)

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin was born on 21 January 1869, in the tiny village of Pokrovskoye. He grew up in a peasant household, married, and fathered children. In his late twenties he went on a long religious journey that people later called a conversion. He returned different in look and manner. Villagers who had heard his intense prayer and long storytelling, described him as a person who could hold a group’s attention by the sound of his voice and the weight of his stare. He never became an ordained cleric. He also did not belong to the official Orthodox hierarchy. The name most often used for him back then was strannik, a wandering holy man who prayed, fasted, and attracted followers without formal office. Rumours soon attached to his name, including whispered links to fringe sects such as the Khlysty. Serious proof of formal membership did not materialise but the rumours helped to create an early aura of danger and mystery around him.

Into Saint Petersburg and first contact with the imperial household (early 1900s–1906)

Rasputin travelled to St. Petersburg in the early years of the twentieth century. The capital attracted the strange and the spiritual. His peasant bluntness set him apart among salons that were used to foreign mystics and fashionable gurus. Over a few years he met clerics, aristocratic women and some nobles. His name moved through private networks until the imperial household heard of him. The first recorded meeting with the Romanovs took place around November 1905. That meeting did not immediately change anything, yet the imperial family was already vulnerable after political shocks and personal anxieties. The arrival of a man who claimed spiritual gifts therefore mattered more than a single visit might otherwise have.

Alexei’s illness and the dawning of emotional trust (1906–1909)

Alexei Nikolaevich, the heir, suffered from haemophilia. Bleeding episodes could be sudden and terrifying. On several occasions Rasputin was brought into the palace to sit with the boy during these crises. Nurses and some doctors later recorded that Alexei calmed in Rasputin’s presence. The Empress Alexandra wrote private notes and letters showing gratitude for those nights when her son slept and seemed less in danger. Medical historians today offer several possible, non-contradictory explanations: the child’s condition could undergo natural remission; Rasputin’s presence might have reduced panic and thus physiological stress; his practical counsel could have led caretakers to avoid harmful treatments. Contemporary observers also described Rasputin’s effect in the language of suggestion or hypnotic-like calm. Those repeated episodes of consolation and apparent improvement created the emotional foundation for a trust which extended far beyond the nursery.

Intimacy, letters and informal channels of influence (1908–1914)

A trusted personal bond made Rasputin more than a spiritual visitor. Anna Vyrubova, the Empress’s close friend and lady-in-waiting, became one of his most ardent defenders. She wrote letters and vouched for him in palace corridors. Rasputin began to visit private rooms, to pray beside icons in the palaces, and to correspond with members of the household. That intimacy created an informal channel. Petitioners and courtiers learned that mentioning Rasputin’s name to Alexandra could help open doors. No formal office nor salary ever made him part of government. His power came from being indispensable to the Empress. Private recommendations often translated into reshuffling of officials, early favours, or protection from scandal. The system of a personal monarchy meant that such private influence had public consequences.

The odd mix of methods: charisma, suggestion, and the talk of hypnosis (1908–1914)

People who met Rasputin later described the same traits: a heavy, fixed gaze; a voice that slowed and steadied; a prayer that filled a room. His daughter Maria and other contemporaries recalled how his intensity seemed to transfer calm to anxious people. Some observers used the term hypnosis to explain this effect. Medical and historical readers now favour a blended explanation: persuasive speech, emotional intelligence, timing, faith, and accidental medical prudence, all probably combined to create the impression of healing. The evidence does not prove formal hypnotism in a clinical sense, yet numerous eyewitness accounts about his stare and manner made the charge plausible in public imagination. That ambiguity was crucial. Supporters believed in a genuine gift but detractors saw it as manipulation. The lack of a single, decisive explanation allowed myth to grow.

Private faults, public rumour: drinking and sexual scandals (1909–1916)

Rasputin’s private life worsened his public image. He drank at times, told coarse jokes, and kept friendships with several aristocratic women. Salon gossip recorded alleged improper visits and whispered intimacies. The press and political opponents used these stories relentlessly against him and by extension, against the imperial household. Satirical cartoons and pamphlets depicted the Empress as enthralled and the palace as morally decayed. Many of the stories were hearsay, some were exaggeration and a few were based on eyewitness reports. The steady drumbeat of rumour made Rasputin a symbol of everything critics said was wrong with the monarchy. Ordinary Russians, stretched by war shortages and repeated military setbacks, were apt to believe the worst. In that atmosphere scandal had power equal to any policy error.

A violent attempt and the halo of survival (1914)

Violent opposition to Rasputin appeared years before the final conspiracy. Driven by religious zeal and indignation at Rasputin’s influence, Khioniya Guseva, peasant woman of Syzransky Uyezd, stabbed him in the abdomen while he was travelling in Tobolsk. He survived after a serious, protracted recovery. That survival produced two rival narratives. Supporters suggested divine protection or providential resilience. Opponents framed the attack as evidence that credible moral outrage had already gathered around him. The stabbing hardened public feeling, raised the stakes of confronting Rasputin, and added another layer to his growing legend.

War, the Tsar at the front, and the widening of influence (1915–1916)

In 1915 the Tsar left St. Petersburg to take direct command of the Russian armies. He placed domestic governance largely in the hands of the Empress. That shift converted private preferences into decisions that mattered for the whole nation. Rasputin advised Alexandra about whom she could trust and whom she should favour. Contemporary letters and later scholarship show that a number of ministerial reshuffles followed Imperial interventions. Historians stress that Rasputin did not dictate military strategy nor did he run ministries. He did, however, influence personnel choices. Those choices were crucial because in wartime, good administration and steady management of logistics and supplies were vital. Where trusted judgment failed, the results worsened shortages and undermined morale. The sight of a peasant adviser shaping appointments while soldiers suffered became deeply resented by many.

The decision to remove him and the murder night (late December 1916)

By late 1916 leading nobles had concluded that Rasputin was a danger to the monarchy. Felix Yusupov, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Vladimir Purishkevich, and others plotted to remove him by force. They invited him to the Moika Palace on the night of 30 December 1916. Prince Yusupov’s memoirs later presented an elaborate, theatrical account of the occasion: poisoned cakes and wine; a wait to see the poison fail, a gunshot, a prolonged struggle, final shots and the body thrown into the river. The press seized on that drama. Forensic evidence and subsequent historians complicate the theatrical script. The autopsy emphasised gunshot wounds as the cause of death and did not support the more sensational claims about immunity to poison or a long, supernatural struggle. Modern readers therefore see Yusupov’s account as part fact and part self-fashioning by the killers. The murder did not restore the monarchy. The Tsar abdicated within months.

The ambiguity that made the story contagious

The defining quality of Rasputin’s story is ambiguity. He soothed a child, and a mother trusted him for that reason. He offered advice that sometimes did no harm and sometimes may have helped. He drank and joked and behaved in ways that offended genteel society. He survived an assassination attempt in 1914 and then fell to a murderous conspiracy in 1916. The records include private letters, memoirs, gossip, medical notes, and press campaigns. Each source carries a mixture of sincerity, bias, and invention. The result is a life that can be told as a miracle story or as a scandal story depending on the teller. That freedom of interpretation let myth shape policy: rumours about the mystic’s control helped to produce the very political violence that ended his life and hastened the dynasty’s fall.

Conclusion

Rasputin was neither a malevolent genius nor a harmless eccentric. He was a fallible person who, at a time of great exposure, found himself in a ruling home. His presence offered solace, which grew into power inside a system blending personal belief and public responsibility. The catastrophe is not only in his behaviour but also in the frailty of systems that let rumour, faith, and individual dependency guide government policy. The narrative of Rasputin lives on since it demonstrates how personal connections, magnified by doubt and terror, can change the destiny of an Empire.