Hair in South Asian History: A Cultural Perspective

-Oishee Bose

What made people spend time braiding, oiling, winding, braiding again, knotting and adorning hair across centuries until whole guilds of specialists existed to do it for them? Hair reveals much about one’s age, lineage and care and unlike clothing, it cannot be changed by a single purchase. In South Asia, hair became a language: a slow, visible script that recorded ritual belonging, caste and occupation, regional taste, political allegiance and spiritual aspiration.

Harappan cities: combs, mirrors and coiled buns (c. 3300–1900 BCE)

The earliest visible chapter opens in the workshops and houses of the mature Indus cities. Excavations at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa recovered small, polished mirrors, combs of bone and ivory, and pin-like implements that were clearly cosmetic tools that could be called evidence of grooming as a household practice, not an elite whim. Bronze and terracotta figurines give us the look. The little bronze commonly called the “Dancing Girl” is famously posed with a heavy coiled mass of hair falling over one shoulder; another steatite head, labelled the “Priest-King,” wears a fillet and shows carefully combed hair held back from the face. These objects show something more than just hairstyles: they tell us that hairstyling was embedded in urban household economies and that artisans like metalworkers and comb-makers made tools to serve a grooming culture.

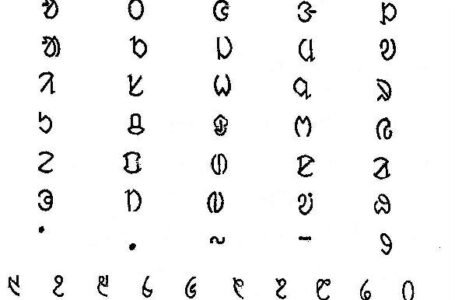

The Vedic and epic lexical world: śikhā, kurīra, opaśa (c. 1500–500 BCE)

As material traces thin in some regions, literary registers grow dense. Vedic and early śruti/Smṛti texts do not describe step-by-step hairdressing but they name coiffures and prescribe their ritual meanings. A central term is śikhā, a tuft or lock left after partial shaving, which becomes a visible index of sacrificial competence and priestly office in Brahmanical codes. Vedic hymns and later ritual manuals also mention coiffural types such as kaparda (tresses), kurīra (a horn-like top knot), and opaśa (a piled knob), each carrying social meanings: the warrior’s knot for combat, the bride’s braided decorations for marriage rites, the śikhā for those eligible to perform Vedic rites. Tonsure itself (full or partial shaving) is repeatedly present in rites of passage, be it birth, initiation (upanayana), pilgrimage and mourning, so that both presence and deliberate absence of hair become communicative acts.

These textual categories are crucial because they show how hair was governed by law and ritual: the body’s hair became as much a part of liturgy as a sacrificial formula.

Early historic and Mauryan frames: chignons, bands and shaped curls (c. 4th–2nd century BCE)

Sculpture from the early historic period begins to freeze the Vedic vocabulary into visible types. Women appear with centre-parted hair, looped buns and decorative fillets; men show cropped forms or tied knots. The Didarganj and other Mauryan-period heads reveal careful combing and restrained hairlines; these are not random textures but groomed, repeatable styles that would have taken skilled hands to produce. The presence of fillets and diadems in many male and female heads also suggests that hair and headgear were integrated: the hair supported ornament and was itself a surface for public display.

The classical visual grammar: fan-buns, front chignons and the polished ideal (c. 1st century BCE–6th century CE)

From Bharhut and Sanchi to Gupta reliefs and small bronzes, a clearer lexicon of courtly coiffure emerges. The fan-bun, a fan-shaped front knot often found on yakshi or Śālabhañjikā figures, recurs in donor panels and narrative scenes; low rear chignons, looped braids, and delicate ringlets frame faces in Gupta terracottas and bronzes. Sculptors painstakingly carved tiny curls and the notches where jeweled pins would have sat. These stone and metal images are not mere style guides; they were part of a courtly aesthetic that associated balanced, calm faces and composed hair with ideal femininity and sovereign order. That precision in stone points to real-life hairdressers able to produce complex arrangements for ritual and courtly display.

Braids across time: practical solution, ritual canvas

While courtly buns evolve, the braid (plait) remains a constant, visible from Harappan terracottas through medieval donor panels to modern weddings. A long single braid often functions as a sign of married status; multiple plaits or shorter braids can mark youth, occupational labour, or regional taste. Braids are also sites for ornament: gold thread, beads and flowers appear woven into plaits in medieval records. In many communities, a bride’s plait was a repository of portable wealth — ornaments could be removed, pledged or sold, which means the braid was both intimate style and economic object. This combination of practicality and symbolism helps explain the braid’s persistence.

Ascetic hair and the jata: renunciation written in locks

In a society where control and order often signified virtue, the ascetic jata (matted locks) deliberately inverted the domestic aesthetic. On Shaiva and yogic images the matted mass is stylised with twisted, tied, sometimes piled high and texts praise jata as the outward sign of tapas, spiritual discipline earned through austerity. Hagiographies narrate transformations where the princely or courtly hair becomes a saintly jata; the hair’s changed state becomes a moral biography. Far from being a mere lack of grooming, jata are crafted, managed in a different register and recognised across religious communities.

Regional grammars: Chola coils, Pala crowns and tribal pragmatics (c. 7th–13th centuries)

Regional courts develop distinct hair idioms. Chola bronzes show high, layered coils and netted hair retia that serve as both coiffure and crown for dancers and goddesses; Pala images of eastern India display crowned, tiered hair that merges with ceremonial headgear. At the same time, hill and tribal communities fashioned short, practical bindings or cropped styles adapted to labour and climate, forms less visible in monumental art but preserved in later travel accounts and ethnography. The result is a plural landscape where regional taste, climate and social structure shape how hair is worn.

Turbans, sarpech and Mughal refinements: hybrid headgear (c. 13th–18th centuries)

The medieval and early modern periods introduced or expanded headgear languages. For men, the turban becomes a highly codified sign: style, fold, height, and the presence of jewels such as a sarpech denote rank, region and office. Mughal miniatures preserve the precision of such coding: neat beards, shaped moustaches, and jewelled aigrettes form a courtly silhouette. Women at Mughal courts combined local braid and bun forms with pearl strings, nets and veils, producing cross-cultural aesthetics that fused indigenous techniques with Persianate ornamentation. Court inventories and household lists from palaces record hair-nets, pearl strings and jeweled pins among luxury items, confirming that hair ornament was part of palace economies.

Facial hair and martial identity

Facial hair — moustaches and beards developed their own semiotics. Epic traditions valourise sweeping moustaches as a warrior’s badge; Rajput and Maratha portraiture preserves distinct moustache shapes tied to martial pride. Sikh practice fuses uncut hair (kesh) with the tied turban (dastār) to articulate a coded religious identity in which hair is communal law as much as private look.

Tools, oils and the material economy of coiffure

Hairstyles required markets and materials. The archaeological record yields combs and mirrors; textual and household lists name oils (sesame, coconut), soapberries (reetha) as an equivalent of shampoo, fragrant pastes (sandal, aromatic herbs) and ingredients for pomades. Jewellers fabricated pins and hair-nets; barbers and hairdressers practiced techniques passed from parent to child. These interlinked crafts of oil-pressers, metalworkers, jewellers, and barbers made hairstyle a micro-economy wherever polished nets of social life existed. Archaeological catalogues and temple records document how hair ornament formed part of ritual treasuries.

The Nai (Nai/Nayi/Sain) barbers: custodians of the head

If hair is social writing, someone has to write it. Across north and central India the Nai (also spelled Nai/Nayi, in some regions Sain) were the hereditary caste of barbers. Ethnographic and colonial surveys show they performed cutting, shaving, scalp-massage, bridal plaiting and ritual tonsure; they attended weddings and funerals and in many villages they knew the precise moments when rites required a particular shave or parting. Barbers often held ambivalent social positions: indispensable for ritual and hygiene yet subject to taboos around purity and touch. Scholarship documents this ambivalent, highly skilled occupation; modern studies note that many Nais today have diversified, while their ritual knowledge continues to shape life-cycle practice.

A Nai barber’s skill is not only in cutting but in timing: knowing when a bride’s plait should be tied, which oil to use for a priest’s śikhā, how to shroud the head during a funeral shave without violating ritual strictures.

Tonsure as offering; Tirumala and the market for sacred hair

One of the most striking continuities between ancient practice and modern economy is the ritual offering of hair. Devotees shave their heads in fulfilment of vows; temples collect the tonsured hair and sometimes convert it into revenue. The Tirumala (Tirupati) shrine provides a startling modern example: the daily tonsuring of thousands of pilgrims is organised at scale and the collected hair has become a significant revenue source, sold through auctions to wig and extension manufacturers around the world. That private hair which was once the sign of personal surrender is now being circulated in global hair markets is a striking continuity in India’s long history.

Colonial modernity: barbershops, photographs and changing styles

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries introduced European barbering techniques, municipal hygiene regimes and photographic portraiture. Soldiers and municipal workers adopted cropped cuts; urban elites experimented with western partings and shorter cuts in city studios. Women’s hairstyles underwent a noticeable shift from traditional ritual and community forms toward domestic, socially moderated presentation. Visual culture of the late 19th century, especially studio photography and paintings provides our best evidence. Famous paintings like Nair Lady Adorning Her Hair (1873) by Raja Ravi Varma show a Nair woman in a domestic setting arranging a long, oiled, centre-parted hairstyle and adorning it with a garland of jasmine flowers, emphasising both beauty and everyday grooming practice familiar in many Indian households. Such depictions reflect how women’s hair was viewed within the private sphere, associated with refinement, modesty, and respectable womanhood rather than public spectacle, mirroring evolving norms in colonial society. Colonial-era studio portraits of women from prominent families similarly show centre parts, neatly tied back hair, braids or low buns, often left plain or garnished with flowers rather than heavy ornamentation, contrasting with far more ornate medieval temple styles. These images highlight how Victorian ideals of modesty and domesticity blended with indigenous forms, making long braids and simple buns markers of respectable femininity during the colonial period. In the late Colonial period, Salon culture commercialised many hereditary barber skills, merging older craftsmanship with new tools and global techniques.

Cinema, globalisation and contemporary plurality

The twentieth century’s mass media, especially cinema, created national standards and fantasies of beauty: flowing tresses, set waves, particular fringe cuts. Globalisation added perms, chemical straightening and colouring into the menu available at urban salons. Yet ancient practices persist strongly: Sikh kesh remains an institutionalised religious discipline; Śaiva jata and ritual tonsure persist in pilgrimage circuits; bridal plaits are still woven with family beads and flowers. Contemporary India is therefore a multiplex: ancient techniques sit beside chemical straighteners in the same market, and memory keeps older styles meaningful in ritual and region.

Conclusion

Indian hairstyles are not small details at the edge of history; they are among its most intimate records. Long before most people left written words behind, they carried meaning on their heads. Hair marked birth and death, marriage and renunciation, caste and occupation, power and devotion. It told others who someone was, where they belonged and what kind of life they lived.

Across centuries, styles changed, yet many gestures endured. The Harappan coil, the Vedic śikhā, the braided plait, the ascetic jata, the carefully folded turban, the pilgrim’s shaved head, all belong to a long, shared grammar. They adapted to new religions, courts and economies without losing their emotional weight.

To read hairstyles is to come close to everyday history. History, here, lives not only in stone or text, but on practice and living, growing bodies.