The Bargi Terror in the Bengali Memory

-Oishee Bose

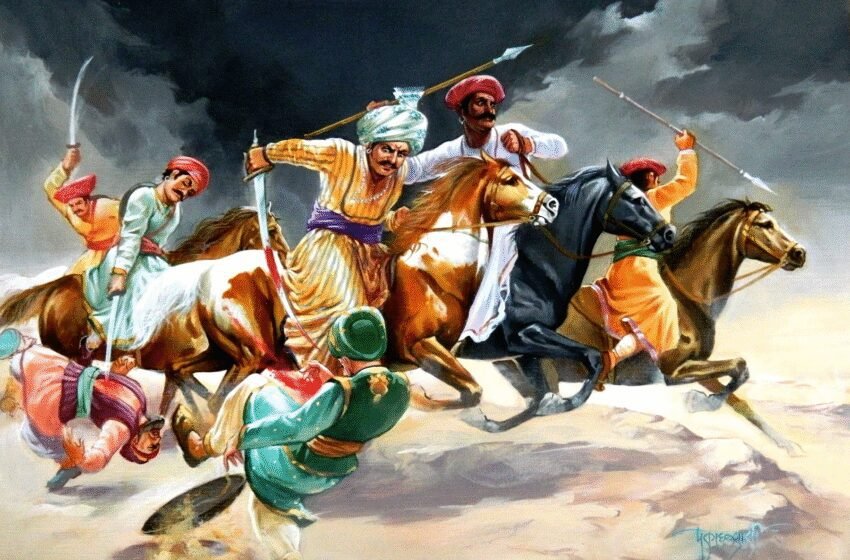

The popular Bengali lullaby, “Khoka ghumālo, pāṛā jūṛālo, Bargi elo deshe” sounds like an ordinary domestic verse. However, the lines carry a weight: a mother’s low voice folded over the image of a ruined harvest, vanished savings and a threat that arrives with the night. This lullaby is not merely a song to hush a child; it is a compressed historical chronicle, a survivor’s memory turned into an instruction for living. The Bargis, the light cavalry of the Maratha incursions into Bengal in the 1740s, did not merely fight armies: they rewrote the emotional map of everyday life in the region. Their presence is preserved not only in histories but in lullabies, street names, poems, place-bound anxieties, and the silences of ruined villages. This can be traced in the various components through which Bargi memory lives on in Bengali cultural life — oral culture, semi-historical poetry, colonial geography, ruined trades, village legends, metaphors, and urban street-topography.

A brief historical overview: Who were the Bargis, why Bengal, and how fear spread

“Bargi” (Bengali borgi) is the local rendering of bargir, a term used in Deccan/Mughal military vocabulary for cavalry whose horses and equipment were supplied by the state. In the 1740s the Maratha leader Raghuji Bhonsle (Nagpur) sent fast cavalry detachments into the wealthy countryside of the Bengal Subah. These light horsemen known as Bargis were not sent for long occupation but for lightning raids: quick entry, plunder, and withdrawal. The Maratha campaigns were part of a larger Maratha expansion and the breakdown of central Mughal authority; they sought chauth (a tributary levy) and rich booty from Bengal’s prosperous agrarian and textile economy. Between roughly 1742 and 1751 Bengal endured repeated invasions and counter-raids, and the Bargi detachments were the human face of that terror: mobile, brutal, and unpredictable. The net effect was staggering dislocation, ruined harvests, burned villages, the Eastward flight of artisans and peasants, the collapse of some artisanal industries, and permanent trauma in oral and written memory.

These facts are not merely the abstract findings of later historians: contemporary and near-contemporary chronicles, Persian histories, Dutch and Company records, and local Bengali compositions record how the Bargis plundered, how Nawab Alivardi Khan struggled to defend provinces, and how ordinary people fled or hid. The sheer horror and frequency of raids explain why Bengal’s social memory turned the Bargi into an archetype of sudden predation rather than a mere historical case.

Oral traditions and lullabies: trauma sung to sleep

The lullaby mentioned at the top “Khoka ghumālo, pāṛā jūṛālo, Bargi elo deshe; Bulbulite dhān kheyechhe, khājānā debo kīshe” (Baby’s gone to sleep, neighbourhood is quiet, Bargis have attacked Bengal; the sparrows have destroyed our crop, how will we pay taxes?) is the most famous example of Bargi memory lodged in domestic oral culture. It appears in multiple printed folklore collections and is cited repeatedly in popular and scholarly writing as evidence of how deep the anxieties were: the song compresses tax anxiety (who will pay khājānā), crop failure, and the threat of night-time raids into a few lines sung to infants. Such lullabies accomplish a double work: they soothe and they warn; they rehearse how to imagine danger as routine.

Beyond the lullaby, countless local rhymes and “scare-songs” invoked the Bargi to enforce caution among children—“do not wander at night; do not go near the fields at dusk.” In many villages of Hooghly, Burdwan, Birbhum and Medinipur, oral variants survive where “Bargi” becomes shorthand for any predatory outsider. These riddles and rhymes are not fancies, they are mnemonic devices for lived vulnerability, orally transmitted in the absence of formal archives.

Village narratives and place-specific legends:

Village-level narratives often give Bargi memory its most piercing immediacy. Where chronicles record campaigns and casualties, family lore records where the smoke rose and which household never returned. Local tales like Bargi-r galpa tell stories of women rushing into the paddy fields, of certain groves that became no-man’s-land, and of the stones that mark mass graves or charred temple plinths. The Maharashtra Purāṇa itself narrates such scenes of burning villages, cattle driven off, Brahmins and sannyasis fleeing and local memory often maps these lines onto particular places like Radhanagar or villages near Katwa and Burdwan. These place stories are performative history: they teach children which paths to avoid and which kinship networks to trust in times of crisis.

Language, metaphor and cultural archetypes: Bargi as predation

Over time “Bargi” became a metaphor in Bengali usage. To say someone entered “like a Bargi” is to describe sudden and destructive intrusion; to call someone “bargi” in a moralised context is to condemn predatory, lawless behaviour. The lyrical rhyme of the lullaby converts an historical actor into an archetype: Bargi = suddenness + violence + dislocation. This is a classic process in cultural memory studies: historical specificity yields to metaphor when a phenomenon is repeatedly experienced and orally transmitted. The Bargi became a linguistic shorthand in idioms, proverbs, and cautionary tales, much as floods and famines have their own idiomatic presence in deltaic cultures.

Semi-historical poetry: Gangaram’s Maharashtra Purāṇa and the making of moral memory

If oral songs are compressed memory, the Maharashtra Purāṇa, a Bengali narrative poem by Gangaram Dev Chowdhury, provides a literary bridge between lived experience and a theological–moral cosmos. Composed and copied in the mid-eighteenth century (a colophon dates part of the extant manuscript to 1751), the text retells Maratha invasions in the mode of purāṇic narrative: the world is sinful, gods intervene, and the Marathas appear as forces of destruction sent from the south. Gangaram’s poem is unusually detailed for a vernacular, near-contemporary account; historians have long used it as a primary source precisely because it records tactics, routings, and village-level devastation with striking specificity. The Purāṇa thus converts military raids into moral-cosmic catastrophe, turning trauma into a cautionary narrative and embedding it in religious idiom.

Importantly, scholars stress the Maharashtra Purāṇa’s dual status: it is both literary and documentary. As observed by Kumkum Chatterjee, it adopts the language of mangal-kāvya and Purāṇic form while recounting historical plunder, becoming an ideal source for later cultural memory, legitimising the Bargi as both historical foe and mythic antagonist. Editors and translators (Dimock and Gupta’s critical edition, among others) have underlined its value for historians and folklorists alike.

Persian chronicles, Company records and the official archive

While Bengali vernacular poetry preserved feeling and village-level detail, Persian chronicles and Company records provide military and diplomatic context and confirm the extent of atrocities and fear present in the oral or literary references. Works like Siyar-ul-Mutakhkhirin (a Persian history of the era) and Riyaz-us-Salatin include accounts of Maratha maneuvers, Alivardi’s responses, and the uncertain politics that allowed Nagpur cavalry to penetrate Bengal. European factory journals corroborate the scale of disruption: Company officials, Dutch factory reports, and travel memoirs repeatedly mention the Bargi’s speed, the burning of villages, and the flight of artisans to Calcutta. Together, these textual strata, vernacular poetry, Persian chronicles, and European records create a multilayered archive in which cultural memory and official record overlap.

Urban geography and spatial memory: the Maratha Ditch, Fort William, Circular Road, and lanes

Physical urban traces of Bargi fear survive in Kolkata’s very streets. In the early 1740s the English East India Company and local authorities dug an entrenchment, the Maratha (Mahratta) Ditch in the north of Fort William as a defensive measure against cavalry raids. Although the ditch was never completed (the Maratha threat receded and the ditch eventually lost military purpose), its line shaped the city: parts of it were filled and paved to create the Upper and Lower Circular Roads (today Acharya Prafulla Chandra Road and A.J.C. Bose Road), and a small street named Maratha Ditch Lane survives in north Kolkata as a toponymic fossil of that fear. In other words, a defensive response to Bargi raids was fossilised into the city’s morphology—lanes, circular roads and the boundary between “inside” and “outside.”

Fort William, the Company’s defensive compound, also took on new urgency in the Bargi decade; Company records and later histories report hurried fortification works and anxieties among Europeans and local elites about saving goods, records, and people. This also provided another justification for the Company to build the Fort, which would further escalate their conflict with Siraj-ud-Daula. The later conversion of Maratha Ditch into major thoroughfares (the Circular Road) makes the Bargi’s imprint permanent: everyday commutes in Calcutta/ Kolkata quietly trace the line where people once feared night raids.

A related spatial memory is embedded in the suburban map: the old villages that became Dihi Panchannagram (the 33 villages around Calcutta) were originally beyond the Maratha Ditch’s protective line and were integrated into the city later. The very identity of neighbourhoods as “suburb” or “inside the ditch” captures old spatial hierarchies of safety and exposure.

Villages, ruined trades, and collective economic memory: Radhanagar, silk, and the ruined loom

The Bargi raids were not only human tragedies; they were economic shocks. Contemporary reports and later scholarship note the devastation of artisan industries like silk weavers, mulberry cultivators, silk-winding houses and cottage looms were especially vulnerable to horse-borne raids. The Cossimbazar factory (a European trading post) reported in the 1740s that weavers’ houses and looms were burned, and the loss of specialised labour and capital had long-term effects on textile production. One illustrative case is Radhanagar, a noted silk-rearing centre in parts of Midnapore. Vernacular records recount how Bhaskar’s forces burned and looted the locality in their campaigning through Medinipur, leaving the silk economy devastated. The disruption of trades is central to the Bargi memory: the cry in the lullaby—“Bulbulite dhān kheyechhe, khājānā debo kīshe?” (the sparrows have destroyed our crop, how will we pay taxes?) is simultaneously fiscal, agrarian, and artisanal.

These economic losses were not only material; they were social. The flight of skilled weavers to safer districts, the destruction of looms, and the collapse of local markets meant that families lost intergenerational livelihoods. Such losses feed memory: later generations remembered abandoned looms, empty dye-pits, and temples without their donor class. In other words, Bargi memory is built into the very absence of craft.

Absence, silence, and the ethics of memory

One striking aspect of Bargi memory is what is not done: there are almost no grand monuments to the victims, no statewide day of remembrance, no canonical epic that triumphantly narrates resistance. Instead, the memory of Bargi raids disperses into minor cultural forms lullabies, lane names, local poems, family histories. The absence of official commemoration is not indifference but a pattern: catastrophes that are intimate, shaming, and socially diffuse often calcify into private grief and domestic instruction rather than public celebration. The Maharashtra Purāṇa’s Puranic framing, turning violence into cosmic judgement may have also moralised the event in ways that discouraged mere political memorials.

Conclusion: memory as living topography

The Bargi raids did their primary work with hooves and fire; their secondary, longer work was to rewrite the cultural grammar of Bengal. A lullaby becomes a whetstone of historical consciousness; a ditch becomes the skeleton of an arterial road; a burned silk-town becomes a name in an archival note and a ghost in family lore. If historians reconstruct campaigns, poets and mothers preserved the sensations, and if urban planners later paved the ditch to make a road, the living city still carries the Bargi’s signature. To walk Maratha Ditch Lane, to hum that lullaby, to point at a ruined temple and hear that “the Bargis did it”: these are not archaic gestures but present acts of remembering. The Bargi are not simply an episode in 18th-century military history. They are a lens through which we can see how disaster circulates into culture: how fear becomes song, how plunder becomes proverb, and how the urban map remembers the night a village burned.