Somnath temple: India’s timeless Shrine of Faith and Resilience

~ Debashri Mandal

The name of Shiva isn’t unknown to the world. People from the various corners of the earth have known him for ages and generations, irrespective of their religious values and communal beliefs. Lord Shiva, known as Devo ke Dev: Mahadeva, means the God of the Gods in Hindu scriptures such as the Shiva Purana. Despite being the most powerful creator, who destroys before his divine creation, he is often considered the most benevolent and is also known as Bholenath by his devotees. Several temples and shrines dedicated to his entity have been created and established in India and beyond, through the ages and generations. And the Somnath temple of Gujarat is one of a kind.

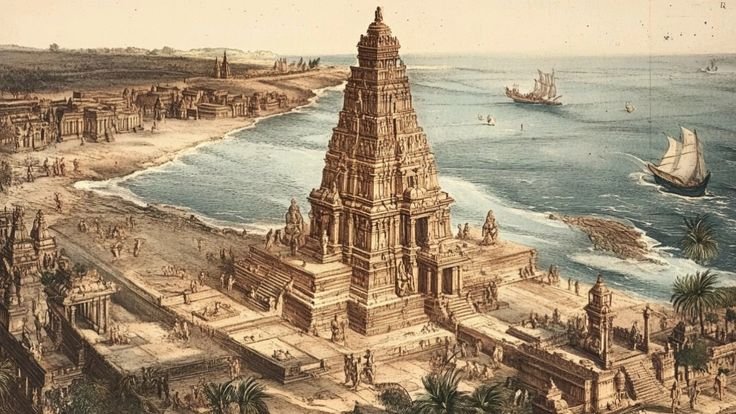

Somnath, meaning the “Lord of the Moon,” is considered one of the most sacred Hindu pilgrimages in India. It is one of the most important of the listed jyotirlingas of Shiva, a fabled tirtha on India’s western coast; its legend reaches back into myth. According to tradition, the moon god Soma once lost his radiance and bathed at the Triveni Sangam (confluence) of the Sarasvati, Hiran, and Kapila rivers at Prabhas Patan (the site of Somnath) to regain it. This tale explains the town’s old name, “Prabhasa” (“lustre”), and the temple’s epithet Someshvara (“Lord of Soma” or the Moon). Ancient Sanskrit poems like Kalidasa’s Raghuvaṃśa (5th century CE) already name Somanatha-Prabhasa among India’s great tirthas. Archaeologists today find no concrete remains of a prehistoric temple on-site, but later records show Somnath was venerated by at least the 9th–10th centuries CE. A Gurjara-Pratihara king in the 800s mentioned visiting “Someshvara,” and Chaulukya (Solanki) king Mularaja (r. c. 940–997) is credited with building the first stone temple here before 997 CE.

Yet the first Somnath shrine faced several disasters to survive today. In 1026 CE, during the reign of Bhima I of Gujarat, Mahmud of Ghazni led his Turkic army across the Thar Desert and sacked Somnath. Medieval chroniclers record that Mahmud desecrated the golden Shiva jyotirlinga, plundered temple treasures (reportedly millions of dinars of gold), and carried them off to Ghazni. Multiple contemporaries (Al-Biruni, Gardizi, Ibn al-Athir, etc.) confirm Mahmud’s raid on Somnath. Although folklore inflates the violence—one tradition claims 50,000 Hindus died defending Somnath—modern historians regard such numbers as formulaic exaggerations of conquest, not literal fact. (An inscription of 1038 CE even hints that the temple was repaired quickly after Ghazni’s raid.) The sack of 1026, however, left a powerful imprint on Indian memory: the iconoclast Mahmud became infamous as a “hero of Islam” in Persian chronicles, and a terror of Hindus, while Indian legends cast Somnath as a symbol of defiance and rebirth.

After Mahmud’s raid, Somnath rose again under Hindu kings, only to be attacked repeatedly over the next 800 years. A famous rebuilding came under the Solanki (Chaulukya) dynasty: King Kumarapala (r.1143–72) was inspired by his guru Bhavabhraspati to rebuild Somnath in stone. In 1169 CE, he erected a grand new Kailash-Meru temple in marble at Prabhas – described as the “grandest and most beautiful of his time” with an enormous 34 and a half-foot-high ceiling over the shrine. Thus, by the late 1100s, Somnath again glittered on the coast.

But the 14th century brought more turmoil. In Alauddin Khalji’s Indian campaigns, his generals Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan swept into Gujarat in 1299. One column marched to Somnath in June 1299, seeking its famed riches. After a brief resistance, the invaders demolished the rebuilt Somnath. Contemporary accounts by Amir Khusrau and Wassaf say the idol of Shiva was looted of its jewels, cut apart, and its fragments carried to Delhi, even used to pave a mosque there. The Khilji conquest left Somnath in ruin again.

Once more, Somnath was restored. In 1308, the Chudasama king Mahipala I of Saurashtra rebuilt the temple, and his son Khengara installed the Shiva linga (lingam) sometime between 1331–1351. This line of local rulers ensured the shrine endured, and 14th-century travelers note that Hindu and even Muslim pilgrims passed the old Somnath on the way to Mecca. But the temple’s troubles continued. In 1395 CE, Zafar Khan (then Delhi’s Gujarat governor, later the first sultan of Gujarat) destroyed Somnath yet again. Sultan Mahmud Begada (ruled 1458–1511) desecrated it in 1451, and later even Mughal emperor Aurangzeb twice targeted Somnath: ordering its destruction in 1665 (although that is unclear if done) and converting whatever remained into a mosque in 1706. Each time, local Hindus regrouped. Around 1783–86 CE, the Maratha queen Ahilyabai Holkar of Indore is credited with building a small new Somnath shrine near the ruins, so that worship could continue despite the dereliction. (That old Ahilyabai temple still stands beside the modern one today.)

By the 19th century, Somnath lay mostly in ruins, of great interest to both archaeologists and the British colonial government. Surveyors like Henry Cousens documented the crumbling carvings and plans of the ruined temple. The British, eager to justify imperialism, even seized on Somnath in a dramatic (though misguided) crusade. In 1842, Lord Ellenborough famously proclaimed he would bring back the sandalwood gates of Somnath from Mahmud Ghazni’s tomb in Afghanistan. General Sir William Nott did recover two ornate gates, only to find they were made of deodar pine—not sandalwood—and clearly European in style. This “Proclamation of the Gates” became notorious after debate in the British Parliament.

Somnath also captured the Victorian imagination. Wilkie Collins’s 1868 novel The Moonstone imagines the theft of a great diamond originally from Somnath (in reality, no such stone was known). Historian Romila Thapar notes that such works reflect the colonial-era fascination with Somnath’s legend. In short, by the late 1800s, Somnath had become as much an archaeological oddity and nationalist symbol as a living temple: its fragmented remains evoked questions about India’s past resilience and the legacy of conquest.

The final rebirth of Somnath came in the upheaval of 1947–51. When India gained independence, and the princely state of Junagadh (in which Somnath lay) briefly acceded to Pakistan, leaders intervened. On November 12, 1947, Deputy Prime Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel arrived in Junagadh to oversee its integration into India and at once “ordered the reconstruction of the Somnath temple.” A national debate followed: Congress leaders like K.M. Munshi (who chaired the Somnath Temple Trust) pressed to rebuild the shrine, and even Jawaharlal Nehru supported it. Mahatma Gandhi blessed the plan as a restoration of India’s heritage but insisted that only public donations (not government funds) pay for it.

Work proceeded swiftly. In October 1950, the remaining ruined structure—including an old mosque built during Aurangzeb’s era—was cleared away by government order. Master masons from the traditional Sompura guild were commissioned to design a new temple in the historic style. Over the next months, they raised a brand-new Somnath Temple on the same spot, built of Bansi granite in the classic Maru-Gurjara (Solanki) architectural tradition. Finally, on 11 May 1951, President Rajendra Prasad performed the kumbhabhisheka (consecration) ceremony and installed a new Shiva linga in the temple. With that, the modern Somnath was born—a clean-slate reconstruction intended to resemble the ancient shrine.

Today’s Somnath Temple is a towering example of Maru-Gurjara architecture, also called the Chaulukya or Solanki style. It follows the Kailash-Mahameru Prasad plan: a high pyramidal spire (sikhara) over the sanctum and a two-story pillared hall. The main spire rises about 15 m above the sanctum, topped by an 8.2 m flagstaff. The rebuilding (late 1940s–1950) integrated recovered fragments of the old temple into the new stonework. Prabhashankarbhai Sompura—scion of the Sompura masons who design Gujarat temples – led the project, incorporating 212 carved panels (many from the ruins) into the walls and pillars. Surviving fragments on the south and southwest sides include defaced reliefs of Shiva as Nataraja, Shiva-Parvati, the sun god Surya, and even Ramayana scenes. Contemporary art historian Henry Cousens remarked that the 19th-century ruins had been “exceedingly richly carved”—similar in style to the famous Luna Vasahi temple at Mount Abu.

Archaeology confirms the temple’s deep roots. Excavations led by B.K. Thapar, in 1950–51, found stone foundation elements dated to around 960–973 CE. Thapar concluded that a large temple (perhaps of the Bhima II era, late 12th century) had existed there. Other scholars, like M.K. Dhavalikar, found evidence of even earlier settlement, but no intact pre-10th-century temple structures. In short, the stone remains suggest Somnath has been a major shrine since at least the 900s–1000s CE. Whether earlier shrines stood there (perhaps wood or brick) is unknown, but the medieval temple ruins clearly followed a north-Indian (Nagara/Vesara-influenced) design.

For Hindus, Somnath remains a peerless pilgrimage. All traditional lists of Shiva’s sacred sites put Somnath first among the twelve Jyotirlingas. The temple has inspired festivals and legends (for example, some say Krishna spent his final days in nearby Prabhasa before entering the stratosphere). Pilgrims flock here from all over India, especially during Mahashivaratri. In Gujarat, it is routinely paired with a visit to Dwarka to the north (the Kashi of the West) – together they are the state’s top Shiva tirthas.

Somnath has also become a symbol beyond religion. In modern India, its story of survival has been invoked as evidence of unbroken faith and cultural unity. A recent government press release put it plainly: “Despite multiple repeated attempts for its destruction… the Somnath Temple stands today as a powerful symbol of resilience, faith and national pride”. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has likewise reflected that the temple endured the first attack in 1026, and “numerous assaults” thereafter without breaking the Hindu people’s resolve. He wrote that each attack on Somnath only “strengthened the sentiment of India’s cultural unity, and the Somnath Temple was repeatedly revived and rebuilt”. In other words, Somnath has come to personify the idea that invaders may ruin temples but cannot destroy India’s heritage or faith.

This national resonance was not accidental. Before independence, Congress leader K.M. Munshi championed Somnath’s cause as a revival of Indian pride. Even the 1951 rebuilding was seen by some commentators as more than an archaeological project – a statement of Hindu renewal after a “thousand years of Muslim domination”. Today, Somnath is taught and debated: Indian textbooks celebrate it as an eternal cultural consciousness, while Pakistani textbooks infamously portray Ghazni’s raid as a celebrated jihad victory. Regardless of perspective, the result is that Somnath has entered a larger mythology. Its gleaming modern temple, back on the edge of the Arabian Sea, is not just an ancient shrine restored – it is a living monument to India’s layered history.

The Somnath Temple is not just a building but a saga. Born in myth and anchored in scripture, it has been destroyed and rebuilt more than a dozen times, witnessing kings, saints, invaders, poets, and politicians. Each generation has added a layer to its story. As one scholar noted, by the 1950s, Somnath’s reconstruction was “not about restoring an ancient architecture” so much as asserting religious and cultural identity. For pilgrims and citizens alike, Somnath’s roar has come full circle: once desecrated, now consecrated anew; once a ruin, now a radiant temple – and through it all, a powerful symbol of India’s enduring faith and unity.