Knots that spoke: Decoding the Inca Quipu

-Oishee Bose

Imagine an empire covering deserts, mountains, and rainforests; governing millions of people; constructing roadways lengthier than those of ancient Rome and incredibly precise cities; but leaving no books, inscriptions or inked pages. Historians have wondered for centuries about this absence. Without writing, how did the Inca retain their history, administer their present, and chart their course?

The answer is not found on parchment scrolls or stone tablets. Rather, it hangs in museum drawers and Andean community treasuries: bundles of cords, dyed in vivid hues, spun from animal fibre, and painstakingly knotted into complex designs. One’s first impression suggests they seem beautiful, even cryptic. Once the intellectual foundation of the biggest Native empire of the Americas, these items known as quipu (or khipu).

Quipu practically overturns everything we think we know about writing. They are not plain-surfaced or alphabetised. Understanding texture, colour, location, and touch is necessary to read these. Still, they registered numbers with mathematical exactness, managed colonial governance, and according to colonial observers as well as contemporary research, they might have even spoken tales, kept names, and delivered messages across great distances.

Quipus are at the heart of one of the most contentious discussions in archaeology and history today: what qualifies as writing? Was the Inca really a civilisation without writing, or did they develop a completely unique form, one that contemporary researchers are just beginning to comprehend?

A Stunning Inca Technology

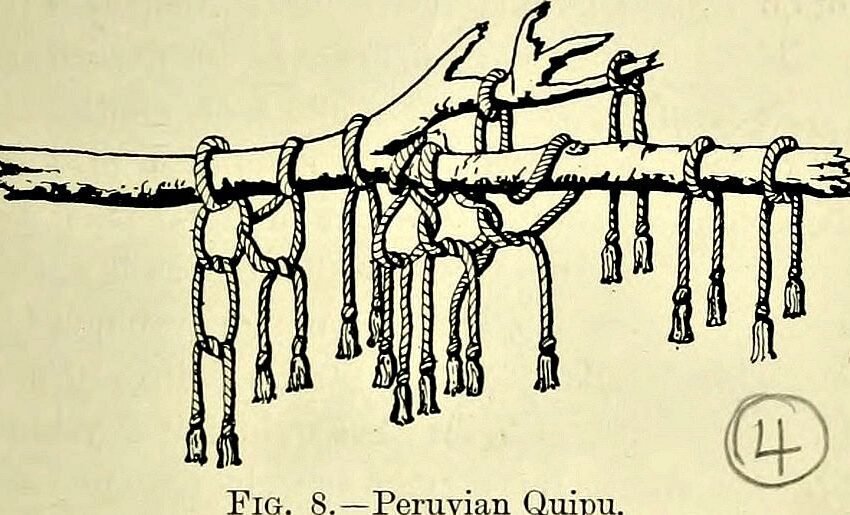

Quipus are strings and knots with different hues, directions of twist, distances, and tactile sensations. Tens of cords and tens of thousands of knots can be included in one surviving quipu. Preserved in museum boxes or cautiously guarded by Andean families, these items reflect the Inca obsession with order, measurement, and memory.

Scholars generally agree on a number of key facts: quipus were essential to Andean governmental life; they encoded numeric data with great accuracy; they survived the first Spanish conquest only in partial amounts; and present academics—archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians are still discussing whether and how quipu coded narrative material that was non-numeric.

Historical Context, Archeology, and Origins

The knotted-cord technologies of the Andean region predate the Inca. Middle Horizon and earlier settings show evidence of cordage and knotting patterns; civilisations like the Wari created proto-quipu-like items and employed textiles extensively. Between c.1400 and the Spanish conquest in the 1530s, the Inca scaled, standardised, and institutionalised knotted-cord systems as a state technology.

Covering a great number of ecological zones and languages, the Inca Empire of Tawantinsuyu extended. Centralised governance demanded instruments that could operate at large scale across language boundaries. Practical, portable, and adaptable quipu was the solution.

Sixteenth-century Spanish sources show a thriving quipu culture. Chroniclers, both natives like Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala and mixed-heritage writers like Garcilaso de la Vega as well as missionaries such Bernabé Cobo and other Jesuit and ecclesiastical observers described quipucamayocs (quipu experts) who spoke aloud, reciting census statistics, tribute lists, and sometimes more complex information. These direct observations set the expectation that quipu were more than just mnemonic beads.

Still, colonial response was hurtful. Many quipus were discarded or destroyed as pagan artefacts during administrative reorganisation and evangelisation. What lives on is far fewer than what once existed and is a corpus dispersed in private collections and museums; its erratic survival defines what we can say about uniformity and variation.

Anatomy of a Quipu: The Variables that Matter

To grasp quipu, imagine a spreadsheet whose rows are cords and whose columns are knot positions but with three-dimensional features that a visual spreadsheet cannot capture.

A quipu typically consists of:

• Primary cord: the main horizontal spine from which pendant cords hang.

• Pendant cords: hanging cords which may carry knots and, in many cases, branch into subsidiary cords.

• Branching cords known as subsidiary cords form hierarchical interactions like nested subtotals in a ledger.

The information is carried not only by the number and kind of knots (single knots, long knots, figure-eight knots) but also by a group of physical features that academics record precisely:

• Placement: the position of a knot along a cord; • Type of knot: the morphological form of the knot; • Number: single vs. grouped knots and numeric values displayed positionally; dyed wools with unique colours and, in some instances, metallic threads; • Material / fibre source: alpaca, llama, vicuña, guanaco, deer hair, among others; tactile differences in fibre typically encode meaning; • Ply and spin direction can be consistent markers; the twist and ply of chords (S- or Z-spin) and ply direction; • Texture and thickness: cord diameter and tactile characteristics; • Relative spacing and distance from the main cord, a farther or nearer knot can signal different units or semantic roles.

For numerical recordkeeping, quipu functioned on a decimal, positional principle: knots toward the free end of a pendant commonly represent units, while knots nearer the primary cord indicate tens, hundreds, and so on. Thus quipu could represent large, precise numbers tracking people, goods, and labour.

Administrative and Accounting System known as Quipu

The most evident agreement of the literature is that quipus were mainly utilised for numerical administration. Surviving instances and documentary evidence confirm that quipu used for: tribute and taxation (lists of required goods or labour contributions); storehouse inventories (quantities of maize, potatoes, textiles, and other staples); labour systems (mit’a obligations and mobilisation records); military logistics (troop counts and provisioning); economic transfers and debt accounting; and census figures (population counts, household tallies).

Modern scientists have verified the correctness of numerical encoding by correlating some quipu records with Spanish colonial documents. This shows that how quipu had served as the administrative backbone of an empire which was unable to rely on a single common spoken language.

Debate over Narrative Content

From the time quipu started receiving academic attention, two poles have struggled: whether quipu was a mnemonic, personal prompts for experts or was it a public, uniform documents used for communicating sophisticated, or possible narrative meaning.

Mnemonic thesis: Many scholars contended in the 20th century that quipus were little more than personal or professional memory aids employed by quipucamayocs to organise oral presentation. On this perspective, quipu did not provide a writing method for the whole community, in the sense of encoding speech or language.

Public-script thesis / semasiographic alternative: Other scholars, most recently Silvia Ferrara being among them, argued for a broader conception. Ferrara emphasises that quipu might have operated as semasiography: a system of signs that conveyed meaning without directly encoding spoken language, akin to mathematical notation, musical scores, or iconographic sign systems. Semasiographic systems can be shared across language communities because they encode meaning or procedures rather than sound. Ferrara’s contribution is conceptual: she reframes quipu not as failed precursors to alphabetic writing but as a legitimate, three-dimensional record technology.

These two perspectives are not mutually exclusive: quipu could be simultaneously administrative, semasiographic, and dependent on oral performance.

The Collata Quipu: A Possible Phonetic Breakthrough

The debate shifted decisively with fieldwork conducted by anthropologist Sabine Hyland in the beginning of 2010s. Hyland studied two quipus kept in the Andean village of San Juan de Collata (often called the Collata quipu). These objects were created in the eighteenth century during a period of local resistance and are preserved by village custodians who assert the claim that these were used as letters exchanged among leaders.

Hyland’s analysis identified several striking features:

• A high symbol count: the Collata quipu display a much larger inventory (around ninety-five distinct symbols) than typical accounting quipu;

• Use of multiple animal fibres like vicuña, alpaca, guanaco, llama, deer hair, and others, where fibre source appears to be a deliberate, readable variable;

• A broad colour palette and complex ply/ply-direction patterns that recur in structured ways across the cords;

• Recurring three-cord terminal sequences that Hyland interprets as lineage (ayllu) names and which she has begun to phonetically read, deciphering at least two lineage names so far.

Hyland argues that these features together form a logosyllabic system: signs encoding syllabic units rather than alphabetic letters. If correct, the Collata quipus are the first reliably identified phonetic or logosyllabic quipu and they show that quipu could function as epistolary or narrative texts.

It is important to emphasise the limits and significance of this claim: the Collata quipus are eighteenth‑century objects from the post‑Inca period but Hyland and others see them as reflecting continuity with Inca-era practices described by Spanish chroniclers. Whether the Collata system is a direct survival of Inca-era phonetic quipu, a regional variant, or a post-contact innovation that adapted older conventions remains a central question.

Continuity, Colonial Contact, and Cautionary Notes

Several important cautions temper the enthusiasm for generalising Hyland’s findings:

• Chronology and influence: Collata quipu date to the 18th century, well after the fall of the Inca state and the colonial period produced many hybrid documents and practices. Some scholars argue these could reflect local innovations or syncretic adaptations influenced by contact with alphabetic writing.

• Regional variation: The Andean world was not monolithic. Quipu forms, materials, and conventions varied regionally and over time. What holds in Huarochiri province (the Collata context) may not apply across Tawantinsuyu.

• Corpus limits: The corpus of surviving quipu is fragmentary and unevenly documented. Estimates of extant of pre-Columbian quipu vary, with widely cited surveys indicating on the order of a thousand or slightly more surviving specimens scattered in museums and collections. Provenance gaps and loss bias must be acknowledged.

Scholars therefore urge caution: Hyland’s discovery opens a new and promising line of evidence but recovering a general phonetic script for all Inca quipu remains an ongoing project.

Modern Methods: Databases, Feature Coding, and Digital Decipherment

A major reason for the recent acceleration in quipu studies is the creation of systematic databases and coding schemes. Pioneering efforts, most prominently, Gary Urton’s Quipu Database Project codify each quipu’s variables: cord colours, knot types, spin/ply direction, position, fibre material, and other attributes.

This digital cataloguing allows computational pattern searches across the body of material. Researchers can search for repeating structural patterns akin to word boundaries and can test their ideas and hypothesis (e.g., whether a particular colour–fibre mix always reflects a place name or feature).

These technical developments bridge computational analysis, archival research, and ethnography. They also show the limitations where this method is not very effective: many quipus are inadequately recorded; museum labels lack provenance; and the tactile handling guiding local readers (touch, texture) is sometimes unattainable in museum storage.

Ethnographic corroboration

Community memory and ethnographic studies support physical evidence. In some Andean settlements, quipu customs endured altered forms well into the 19th and even 20th centuries. Hybrid artefacts like quipu attached to wooden boards or employed with alphabetic marginalia portray the creative encounters between colonial literacies and cord technology.

These living memories helped Hyland identify the Collata objects and provided crucial interpretive purchase: villagers recognised the cords’ meanings and their use as letters. This kind of community‑based verification is rare but invaluable.

Where the Field Stands: Consensus and Open Questions

Current scholarship on the Andean quipu has reached a cautious but meaningful consensus on several foundational points: quipu functioned as central numeric and administrative technology across the Andes; their informational capacity resided not merely in knot counts but in a richly material semiotics encompassing colour, fibre type, knot form, cord position, ply direction, and structural hierarchy; and the creation of large-scale digital catalogues with systematic feature coding, most notably through projects such as Gary Urton’s Quipu Database, has become indispensable to any serious attempt at decipherment. At the same time, major questions which are unanswered continue to drive the field: how often phonetic or logosyllabic quipus were used across Tawantinsuyu and if such systems were nation-wide or limited to certain eras, locations, or communicative purposes; The extent to which quipu meaning relied on verbal performance, embodied knowledge, and indigenous mnemonic customs rather than autonomous inscription; how much standardised quipu conventions actually were throughout a linguistically and culturally varied imperial terrain; and whether further family names, place names, and narrative sequences can be phonetically decoded using a combined application of Sabine Hyland’s fibre-based syllabic hypothesis and database-driven pattern recognition. These arguments taken together highlight how quipu research currently lies on a fruitful centre ground, beyond dismissal as only mnemonic aids, but short of whole decryption, where empirical discoveries keep challenging inherited conceptions of writing itself.

Conclusion: A Different Kind of Literacy

Quipu drives us to expand our vision of what literacy can be. They demonstrate how complex data may be stored and broadcasted by big, developed polities depending on non-alphabetic, tangible technologies. Whether we finally accept a fully phonetic Inca script or a mixed system of numerical, semasiographic, and phonetic symbols, the investigation of quipu has already transformed the earlier popular understanding of the concept of writing.

Conceptual transparency has been pushed by researchers such Silvia Ferrara; methodological instruments have been given by Gary Urton and his team; Sabine Hyland has provided a tangible case possibly showing the existence of phonetic quipu in current local traditions. These lines come together on a straightforward reality: the knots are indicating something deeper than what we had assumed.

The Inca did not fail to write; they wrote differently, across fibre and colour, knot and touch. As we recover more cords from museum drawers and village chests, we will continue to translate the textures of an empire that recorded its life in three dimensions.