Kadamba Empire- First indigenous rulers of Karnataka

~ Debashri Mandal

The Kadamba dynasty is considered to be the first indigenous ruling house of Karnataka, rising in the 4th century CE, to have established a powerful kingdom in the northwestern region of Karnataka. Mayurasharma (also called Mayuravarma), a Brahman from Talagunda in the modern Shivamogga district, was the founder of the Kadamba Dynasty. According to legend, he took up arms after being insulted by a Pallava guard and overthrew Pallava authority and founded an independent realm with its capital at Banavasi (Banavasi) around c.345 CE. Records and inscriptions later confirmed that Talagunda was Mayurasharma’s home, and he was sanctioned by the divinity. Mayurasharma is explicitly identified as the founder of the dynasty by the Talagunda pillar inscription of the mid-5th century. By 365 CE, he had secured his kingdom, passing the throne to his son Kangavarman.

Under Kangavarman (r. 370–395), the Kadamba realm was styled as Dharmamahārāja, the “righteous great king,” and maintained a careful balance of war and diplomacy. He was allied with the dominant northern powers through marriage, and the Talagunda inscription notes his ties with the imperial Guptas and marriage alliances with the Western Ganga dynasty of Talakad. Moreover, he also faced threats from the south; for example, Mayurasharma himself had defeated the armies of the Pallavas of Kanchipuram, probably with help from local hill tribes. Through these means, the Kadambas consolidated a territory roughly encompassing modern Karnataka and parts of the Konkan coast. The Kadamba state reached its greatest peak under Kakusthavarman (c. 430–450). Some sources describe Kakusthavarman as a “powerful ruler” who even conquered the Vakataka kingdom of the Deccan and extended the Kadamba domain as far north as the Narmada River. His reign is considered to be the dynasty’s zenith. According to inscriptions, Kakusthavarman’s younger relatives and ministers governed far-flung provinces; for instance, his son Krishna was appointed maha-pratāpi (“great viceroy”) of the Thriparvata region. (This decentralization later contributed to the fragmentation of Kadamba power).

After Kakusthavarman’s death, the empire was divided into rival branches. His successor, Ravivarman (r. c.485–519), continued to rule from Banavasi, but the southern portion of the former kingdom asserted independence under Krishnavarman I at Triparvata (modern Chandragiri). Internecine warfare ensued: at times the Triparvata branch prevailed; at others it accepted Kadamba overlordship or even acknowledged Pallava suzerainty. Some of the notable rulers included Mrigeshavarman and Harivarman. The dynasty endured a few more generations of instability. Notable rulers included Mrigeshavarman and Harivarman, but by the mid-6th century, real power had shifted to the rising Badami Chalukyas. In c.540–545 CE, during the reign of the last Banavasi king, Ajavarman, Chalukya ruler Pulakeshin II captured Banavasi and ended Kadamba independence. Thereafter, the Kadambas survived only as minor feudatories under larger Kannada empires (Chalukyas, then Rashtrakutas) for several centuries.

The Kadamba administration was a hereditary monarchy with Banavasi as its capital. The king was assisted by a structured bureaucracy and local governors. The inscriptions list many official titles, including the prime minister (pradhāna), steward (manevergaḍe), council secretary (tantrapāla or sabhākāryaṃ sāciva), chief justice (dharmadhyakṣa), physicians, and secretaries, among others. Royal princesses were even appointed as governors of provinces. The kingdom was divided into maṇḍalas (provinces or deśas) and viśayas (districts) for administration. Military titles such as senāpati (army commander) are also attested. Kings typically took on lofty titles like Dharmamaharajadhiraja to emphasize their orthodox Hindu (Vedic) persona. Society in the Kadamba realm was predominantly agrarian. Land grant inscriptions and literature indicate that mixed farming—combining cultivation with cattle-rearing—was widespread, overseen by an influential peasant class known as gavundas (early Gowda communities). The prosperity of a household was measured by both its grain yield and its cattle herds. Kings rewarded services to the state with grants of cultivable and pasture land (kola, khanduga); for example, lands were given to those who defended cattle from thieves. Minor trade and crafts would have existed, especially along the Konkan coast, but the core economy was rural. Caste distinctions mattered: the ruling family was Brahminical by tradition, and Brahmins held important religious and educational roles. However, the Kadambas’ lands also included tribal areas and converted forest to farmland, gradually integrating a diverse populace.

The Kadamba kings were orthodox Hindus who claimed divine sanction (e.g., one legend says Mayurasharma was anointed by Skanda, the God of War). Temples to Shiva, Vishnu, and local deities were built and endowed. However, a remarkable feature of the Kadamba rule was religious pluralism. The kings and their court supported Jainism extensively. Early in his reign, Kakusthavarman (Mayurasharma’s grandson) issued grants that begin with salutations to Bhagavan Jinendra (Mahavira) and end by venerating Rishabha, signaling Jain. Inscriptions of King Mrigeshavarman (r. 455–480) record the construction of a jinalaya (Jain temple) at Palasika (Banavasi/modern Halasi) and generous land grants (33 nivartanas) for Jain monks of different sects. By the late 5th century, multiple Jain orders (Svetambara, Nirgrantha, etc.) are explicitly named in Kadamba records. In fact, basadis (Jain sanctuaries) existed at Palasika from the very beginning of Kadamba rule, and even Brahmin kings like Ravivarma performed merit by building Jain shrines in memory of their fathers. Buddhist influence is less evident, but no doubt the era’s environment of broad tolerance and Sanskrit-Jaina culture is underscored by these epigraphs. The Kadambas continued the Vedic (Shaivite) traditions too: temple inscriptions (like the Talagunda pillar) often open with “Namo Shivaya” invocations.

In the cultural sphere, the Kadambas were patrons of learning and scripture. Inscriptions show that court poets and pandits were well-versed in classical Sanskrit, and many Kadamba edicts are composed in refined Sanskrit verse. At the same time, they elevated the Kannada language as an instrument of administration and literature. In fact, the Kadambas were “the first indigenous dynasty to use Kannada…at an administrative level.” The earliest known Kannada inscription—the Halmidi inscription (dated ~450 CE)—was issued under a Kadamba king (Kakusthavarman). (Earlier Harappan and Mauryan civilizations in the region were not recorded in Kannada.) Talagunda itself was the site of the earliest Agrahara (Brahmin university) in Karnataka, reflecting the fusion of Sanskritic scholarship with emerging regional literatures. Although no great body of secular Kannada literature has survived from the Kadamba period, the dynasty’s promotion of Kannada created a cultural legacy: later Kannada writers proudly traced their heritage to this “broad-based starting point” for Karnataka’s regional identity.

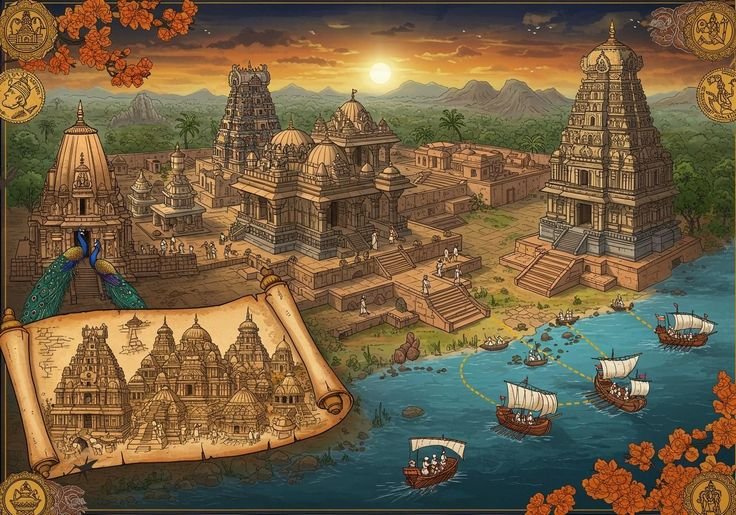

Kadamba architecture pioneered a temple style that influenced all later South Indian dynasties. The signature feature is the Kadamba shikhara, a stepped pyramid tower with a distinctive pot-like kalasha (pinnacle) on top. These shikharas rise in plain tiers, without the elaborate pillared pavilions seen in later Dravidian temples. The form is relatively simple and square in plan, reflecting an indigenous evolution of pyramid superstructures. Surviving examples are rare, but the best-preserved Kadamba monuments are found in the Belgaum district. The 5th-century temples at Halasi (ancient Palasika)—for example, the Bhuvaraha Lakshmi Narasimha Temple—are among the oldest stone temples in Karnataka. Their towers exemplify the Kadamba shikhara, with multiple stepped storeys and a towering kalasha finial. The Kadamba-style tower in the Bhuvaraha Narasimha temple at Halasi illustrates this pyramid-shaped superstructure, which lacks surface ornamentation and tapers straight to its finial. These temples often include a single sanctum (garbhagṛha) on a raised platform and a plain mandapa (hall) supported by simple pillars, without extensive carvings. Notably, Kadamba art influenced the later Chalukya and Hoysala styles: historians recognize Kadamba construction as a “foundation of Chalukya-Hoysala architecture.” Aside from Halasi, other Kadamba monuments include the Madhukeshwara temple at Banavasi, the ancient capital (though it was enlarged by later Hoysalas), and clusters of hill temples at Aihole and Badami built in a proto-Dravidian mode. Large lion motifs and simple geometric decorations (like the simhakŗt lions) appear on ruins at Talagunda and elsewhere, marking royal symbolism. Kadamba rulers also left numerous inscriptions carved on stone pillars and plates. The famous Talagunda pillar inscription (c. 450 CE, in Sanskrit) records the family’s origin myth and genealogy. The Halmidi inscription (Kannada, c. 450 CE) is a Kadamba-era grant on stone. Altogether, these epigraphs and temples attest to the Kadamba legacy in the physical landscape of Karnataka.

The economy of the Kadamba kingdom was based on agriculture, cattle breeding, and the control of regional trade routes. As noted, mixed farming dominated—villagers grew millet, rice, and other grains and also kept herds of cattle, goats, and buffalo. Land revenue and livestock taxes were important, collected by officials called bhojakas and ayuktas. Kings issued grants of nivartana (land units) and tax-free farmland to Brahmins, temples, and warriors; many inscriptions record gifts of land in perpetuity. Some land grants were motivated by defense needs—for example, cultivators who protected herds from thieves might be rewarded with both grazing and tillable land. Maritime trade likely benefited from Kadamba control of the Konkan coast (modern Goa and coastal Karnataka). The dynasty’s successors (the Kadambas of Goa in later centuries) became prominent sea traders. In the early Kadamba period, Banavasi sat on ancient routes linking the Deccan to western ports, so merchants moving spices, horses, and textiles would have passed through. Coin finds (punch-marked and later dynastic issues) indicate integration into broader Indian markets. However, there is little direct evidence of extensive overseas trade under the early Kadambas; their wealth remained tied to inland agrarian resources and tributary vassals. Socially, the Kadamba realm retained older structures. The gavundas were a hereditary rural elite (probably proto-Gowda caste) who managed village agriculture and paid taxes. Brahmins served as priests and scribes (many land grants record gifts to Brahmin scholars). Tribal groups on the Ghats, while gradually becoming settled, contributed to the military as hillfolk auxiliaries. Importantly, Kadamba records and archaeology reveal a relatively tolerant society where multiple faiths coexisted under royal patronage. The era’s inscriptions end with both Shiva and Jain blessings, reflecting this pluralism.

By the mid-6th century, the independent Kadamba state had disintegrated under external pressure. The Chalukya king Pulakeshin II’s conquest of Banavasi around 610 CE formally ended Kadamba sovereignty. Thereafter, for the next few centuries, the Kadamba royal lineage persisted only as regional feudatories. Several minor cadet branches ruled under larger empires: the Kadambas of Goa (established c.960 CE), the Kadambas of Halasi, and later the Kadambas of Hangal (12th–14th centuries) were descended from Banavasi lines. These branches built temples and granted land, but by medieval times, they too faded under pressures from larger kingdoms and the Delhi Sultanate.

Despite their political eclipse, the Kadambas left a lasting impact on Karnataka’s identity and culture. As the first native dynasty of the region, they broke the pattern of outsiders (Mauryas, Satavahanas, and Pallavas) ruling Karnataka. They established Kannada as a royal language and laid the foundations for later Kannada sovereignty. In fact, modern historians regard the Kadamba period as a turning point—a “broad-based historical starting point” for the Kannada-speaking region. Architecturally, the simple Kadamba shikhara endures in temple towers of Karnataka even into the Vijayanagara era and beyond. Many Kannada dynasties (Chalukyas, Hoysalas, and Vijayanagara) retained the usage of Kannada script and bureaucracy that the Kadambas pioneered. Regions that were once Kadamba centers—Banavasi, Halasi, and Chandravati—remain proud archaeological sites. Thus, while the Kadamba Empire lasted only two centuries, its innovations in governance, language, and art helped shape the distinct regional culture of Karnataka for generations to come