History of Shorthand – When Language Refused to Wait

-Prachurya Ghosh

For most of human history, language did not wait for ink. It rushed ahead, impatient, volatile, alive. People spoke faster than hands could move, faster than pens could scratch across stone, parchment, or paper. Speech had urgency. Writing had weight. Between them lay a gap—sometimes small, sometimes catastrophic—and shorthand was born inside that gap.

It is easy now to forget how dangerous forgetting once was. Today, words are endlessly reproducible. We record, replay, archive, cloud-store, transcribe. But for centuries, a spoken sentence could shape law, destroy reputations, start wars, save lives—and then vanish. Shorthand was humanity’s attempt to pin speech down before it escaped.

That is why shorthand was so popular. Not because it was clever. Not because it was elegant. But because it answered fear: the fear that what mattered most would be spoken too quickly to survive.

Before Writing Was Trusted

In early societies, writing itself was not always trusted. Speech felt more real. It carried emotion, authority, presence. Writing was secondary, derivative, sometimes suspicious. Plato famously worried that writing weakened memory. Oral cultures valued repetition, rhythm, and recall. Knowledge lived in bodies and voices.

But this came at a cost. Memory bent. Stories shifted. Authority blurred. The larger societies became, the harder it was to rely on collective recall alone.

Ancient Greece felt this tension acutely. Political life unfolded in assemblies where persuasion mattered more than documentation. Philosophical teaching happened in dialogue, not in books. Socrates never wrote a word. What we know of him exists because others tried—imperfectly—to remember.

Already, there was anxiety. Speech was powerful, but fragile.

Rome and the Crisis of Too Much Speech

Rome turned that anxiety into a full-blown crisis.

The Roman Republic was built on oratory. Law courts, Senate debates, public trials—everything depended on speech. Cicero did not argue cases slowly so that scribes could keep up. He overwhelmed opponents with speed, complexity, rhetorical layering. His words mattered because they shaped verdicts, alliances, futures.

But how do you preserve something that moves that fast?

Marcus Tullius Tiro lived inside this problem. As Cicero’s secretary, he watched meaning dissolve daily. Longhand writing failed. Memory failed. Something else was needed.

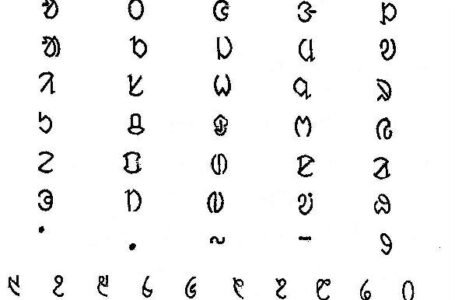

The notae Tironianae were not artistic. They were desperate. Thousands of symbols, abbreviations, contractions—designed to catch language mid-flight. This was shorthand’s first moment of real power. It allowed speech to become text without slowing speech down.

This matters more than is often acknowledged. Shorthand did not just record speeches. It stabilized governance. It allowed Roman political culture to reproduce itself across time. Laws could be cited. Arguments could be revisited. Authority could be anchored.

Without shorthand, Rome would still have spoken—but much of what it said would have disappeared forever.

Shorthand as an Invisible Infrastructure

Once shorthand existed, it became invisible. That is how infrastructure works. Roads are noticed only when they collapse. Memory systems are noticed only when they fail.

Tironian notes spread beyond Cicero. They were adopted by administrators, clerks, later by monks. For centuries, shorthand functioned quietly, compressing language, saving time, preserving repetition.

But invisibility came with danger. Symbolic systems provoke suspicion. In the Middle Ages, when literacy itself was restricted, shorthand looked like secrecy. Compressed writing seemed coded, even occult. At times, shorthand hovered near accusations of magic or forbidden knowledge.

As a result, shorthand retreated. It did not vanish, but it hid. In margins. In annotations. In familiar phrases abbreviated for speed.

Yet the problem it solved never went away.

The Noise Returns: Early Modern Europe

By the sixteenth century, Europe became loud again. The Reformation turned sermons into weapons. Courts expanded. Parliaments argued. Print increased reading, but it did not reduce speech. If anything, it amplified it.

Listening became labor.

This is where shorthand re-enters openly. Timothy Bright’s Characterie was difficult, almost impractical, but it signaled urgency. Thomas Shelton’s Tachygraphy made shorthand usable. Teachable. Portable.

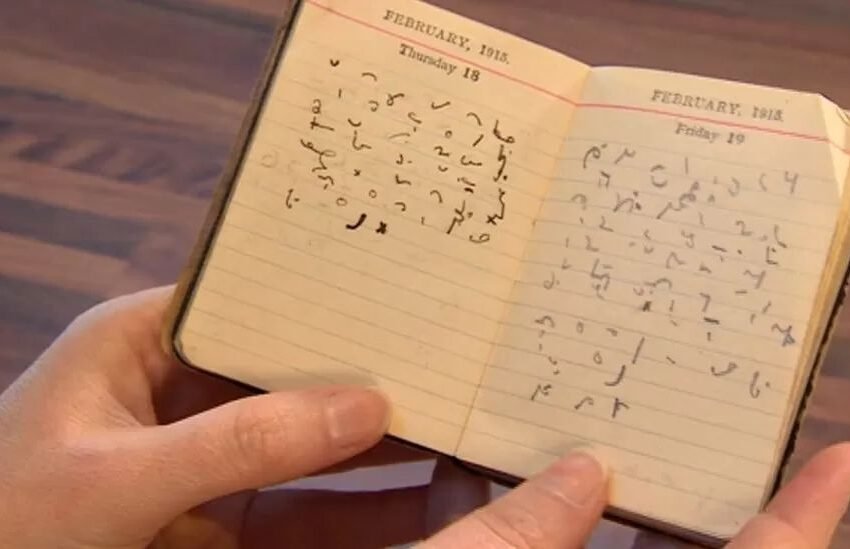

Samuel Pepys shows us why shorthand mattered emotionally. His diary is not just a historical document. It is a human one. He wrote about fear during the plague, ambition at court, sexual guilt, professional anxiety. Shorthand let him write quickly, honestly, privately.

Here shorthand becomes something new: a tool of interiority. Not just capturing others’ words, but one’s own fleeting thoughts. The faster the pen moved, the less filtered the mind became.

Speed created honesty.

Speech Becomes Relentless

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries shattered any remaining balance between speech and writing. Industrialization did not just mechanize labor; it mechanized communication. Offices multiplied. Bureaucracies expanded. Newspapers demanded speed. Courts required accuracy.

Speech became relentless.

Dictation ruled business. Instructions were spoken continuously. Journalists chased voices. Legal stenographers were expected to capture speech verbatim, without error, without pause.

This was shorthand’s golden age of necessity.

Pitman’s phonetic system treated language scientifically. Sounds, not spellings, mattered. Gregg’s flowing curves treated the human hand with kindness, acknowledging fatigue and motion. These systems were not aesthetic preferences; they were ergonomic responses to exhaustion.

Shorthand now meant employment. Survival. Identity.

Commercial schools flourished. Mastery of shorthand could lift someone into the middle class. Failure meant stagnation. Speed was tested. Accuracy measured. Shorthand became one of the few skills where competence was undeniable.

Women Enter the Equation

When women entered office work in large numbers, shorthand became gendered—but it was not trivialized yet. In the early twentieth century, shorthand was power. Secretaries controlled information flow. They heard everything. They recorded everything.

Dictation created dependency. Executives relied on skilled shorthand writers to function. Miss a word, and a deal collapsed. Capture it accurately, and the system flowed.

For women, shorthand was paradoxical. It confined them to clerical roles, yet it also gave them leverage. It provided wages, autonomy, respectability. It was a skill that could not be faked.

The 1950s did not invent shorthand’s popularity; they institutionalized it. High schools taught it. Vocational training standardized it. Alphabet-based systems shortened learning curves.

Popular culture noticed. Films portrayed shorthand as shorthand for competence itself. A woman who could take dictation was modern, intelligent, employable. The flying pencil became a symbol.

But the work was brutal. Dictation did not slow for comprehension. Concentration was absolute. Errors were visible. Mental stamina mattered.

Shorthand demanded everything—and gave something back.

Writers Who Needed Speed

Away from offices, shorthand lived another life. Writers like George Bernard Shaw used it because thought moved too quickly for longhand. Journalists trusted it because interviews were alive, unpredictable. Legal professionals relied on it for notes never meant to be public.

Shorthand here was intimate. It was language without polish. Raw capture. No time to edit. No time to censor.

That is why some people loved it.

The Quiet Collapse

Shorthand did not die dramatically. It faded.

When tape recorders entered offices, the ancient fear dissolved. Speech could be replayed. Frozen. Accuracy no longer depended on reflexes. Typewriters sped transcription. Computers erased physical limits. Digital storage ended scarcity.

Why learn a difficult skill when machines could listen?

The decline was swift because the function vanished. Shorthand had always existed to solve a problem. Once the problem disappeared, so did the urgency.

What Shorthand Really Was

Shorthand was never about symbols. It was about time.

It existed because speech mattered and memory was fragile. It flourished wherever words had consequences and technology lagged behind the human voice.

From Cicero’s Senate to Pepys’ diary, from Shaw’s notebooks to the 1950s office floor, shorthand was the same thing: a fragile bridge between sound and permanence.

For over two thousand years, it held.

Then technology learned to listen.

And shorthand, having done its work, quietly stepped aside.