Rolls-Royce and India: This is How Royal Patronage Built a Legend

-Prachurya Ghosh

When Rolls-Royce began in 1904, there was obviously nothing about it that suggested inevitability. No grand destiny. No certainty that the name would one day be spoken in the same breath as absolute luxury. Henry Royce was not imagining palaces or royal garages. He was annoyed. Annoyed by engines that shook themselves apart, by parts that failed when they should not have, by the general lack of care that defined early automobile manufacturing. Royce wanted things to work properly. That was the obsession.

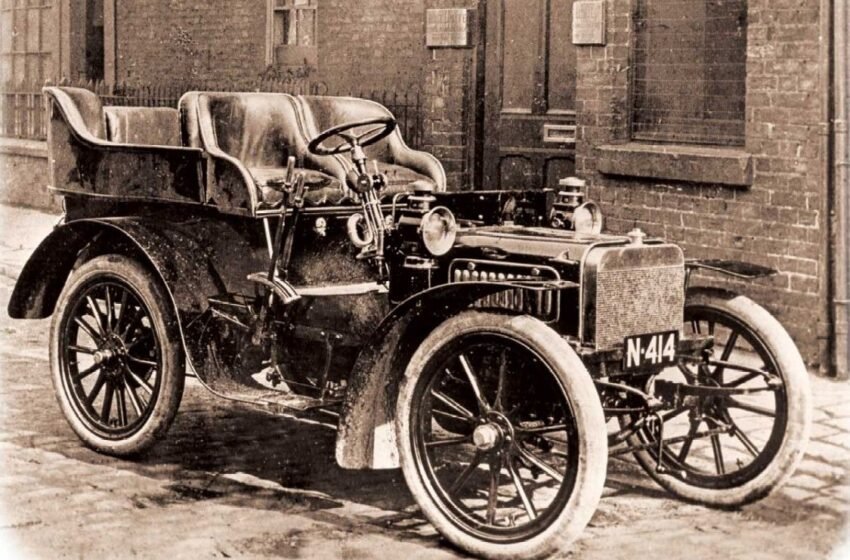

Charles Rolls was different. He belonged to a world where machines were discussed at dinner tables, where novelty carried social weight. For him, automobiles were not only mechanical objects but symbols. When the two men met, the partnership that followed was grounded more in function than fantasy. The early cars of Rolls Royce , including the 10 hp model shown at the Paris Salon in December 1904, did not try to impress through extravagance. They aimed for something quieter. Reliability. Consistency. Control. At the time, this may not have seemed revolutionary. In hindsight, it was everything.

The Indian relationship with Rolls-Royce did not arrive through advertising or careful branding. It emerged slowly, almost accidentally, shaped by environment and expectation rather than intention. India, in the early twentieth century, was a difficult place for machines to survive. Heat softened metal. Dust worked its way into every joint and bearing. Roads were unpredictable, often disappearing altogether. In such conditions, elegance meant very little. A car either endured or it failed, usually in full view of everyone watching.

Indian rulers understood this reality instinctively. They were not dazzled consumers chasing novelty. They were patrons with authority, resources, and very particular requirements. When they looked at automobiles, they looked with interest, yes, but also with doubt. Rolls-Royce entered that space not as a promise, but as a test.

Around 1907, Rolls-Royce made its way into India. Cars were still rare enough to stop traffic, figuratively and literally. Infrastructure existed unevenly, ambition far more than roads. It was during this period that the Maharaja of Gwalior, Madhavrao Scindia II, acquired a Silver Ghost. The purchase itself was notable, but not exceptional. What followed was different. The Maharaja did not confine the car to palace courtyards. He drove it. Across long distances. Over terrain that punished machines without mercy. The car reportedly covered close to a thousand kilometers without serious mechanical failure.

That detail matters because people noticed it. In India, reliability was not theoretical. It was something you could see. The Silver Ghost earned a reputation that had little to do with polish and everything to do with survival. British officials noticed. Other rulers noticed. Stories spread, not through brochures or advertisements, but through observation. Rolls-Royce, in India, began to stand for endurance rather than indulgence. Control rather than display.

By 1911, this reputation found a stage large enough to amplify it. The Delhi Durbar, organized for the coronation of King George V as Emperor of India, was engineered to overwhelm. Every element was deliberate. Rolls-Royce supplied eight identical Silver Ghosts for the event. Identical was important. Uniformity suggested order. Mechanical consistency suggested authority. These cars moved rulers and dignitaries through a ceremony designed to impress and to instruct.

Indian princes watching the spectacle understood the message immediately. The automobile was no longer simply a machine. It had become part of the language of power. Rolls-Royce was not merely participating in this language. It was beginning to define it.

In the decades that followed, the relationship deepened naturally. During the 1920s and 1930s, Rolls-Royce expanded its presence in India through official agents and showrooms in cities like Bombay, Calcutta, and Delhi. This was not speculation. Demand already existed. Indian royalty had adopted the automobile not as novelty, but as necessity. Cars became mobile courts, moving spaces of authority that carried power beyond palace walls.

Before independence in 1947, roughly nine hundred Rolls-Royce cars were imported into India. That number appears often because it is striking. Few markets outside Europe matched it. These were not standard vehicles shipped without thought. They were commissioned carefully. Modified repeatedly. Built to withstand heat, dust, long journeys, hunting expeditions, and ceremonial use. Some were adapted for purdah. Others emphasized height and presence. Every commission said something about the ruler who ordered it.

Indian rulers did not accept limitations easily. They pushed manufacturers. They expected solutions, not explanations. In doing so, they shaped what would later be described as Rolls-Royce’s bespoke tradition. Customization, often framed as a European luxury ideal, owes much to Indian insistence.

And then there is the story that refuses to leave.

The garbage car story has been repeated so often that it now feels almost inevitable. In its most familiar version, Maharaja Jai Singh Prabhakar of Alwar visits a Rolls-Royce showroom in London during the 1920s. He is dressed simply. He is ignored. Perhaps deliberately. Offended, he later returns in full royal attire, purchases every car in the showroom, and ships them to India. Once there, he orders them to be used for collecting garbage. The insult is repaid. Rolls-Royce apologizes. Additional cars are offered. The story ends neatly.

That neatness is exactly what makes it suspicious.

When historians look for evidence, they find nothing. No contemporary newspapers. No British reports. No Indian records. Rolls-Royce’s own archives are silent. No apology. No compensation. No gifted vehicles. Silence matters here.

The story grows weaker when its variations are considered. In some versions, the Maharaja of Patiala replaces the ruler of Alwar. In others, the Nizam of Hyderabad steps in. The characters change. The structure does not. That repetition suggests folklore, not fact.

Even the photographs offered as proof do not survive scrutiny. One widely circulated image showing luxury cars fitted with brooms does not come from India at all. It was taken in Palestine in 1936, where vehicles were modified to clear nails during labor unrest. Removed from its context, the image became something it never was.

So why does the legend persist?

Because it does work. Cultural work. It offers reversal. It imagines an Indian ruler humiliating a British institution through confidence and wealth. In a colonial context, that reversal carries emotional weight. As history, the story is weak. As metaphor, it is powerful.

What cannot be disputed is that Rolls-Royce did not suffer in India. Its reputation did not collapse. It grew. Royal patronage continued. Respect for the engineering remained steady. The myth did not reflect reality. It replaced it.

The real story is quieter. And, in many ways, more compelling.

Indian Maharajas were not impulsive buyers seeking revenge. They were exacting patrons. They tested machines. They demanded adaptation. They expected performance. Rolls-Royce responded, sometimes reluctantly, sometimes creatively. Out of that interaction emerged a brand identity grounded not only in luxury, but in capability.

When the legend is set aside, what remains is a historical partnership. Rolls-Royce found in India one of its earliest and most influential markets. Indian royalty found in Rolls-Royce a machine capable of matching their authority, ambition, and vision of modern rule.

That relationship did not need a dramatic ending.

It only needed to be understood.