The Partition Libraries: How Books Were Lost and Smuggled Across Borders in 1947

-Vani Mishra

When Partition occurred in 1947, the human cost was tremendous. Millions were displaced, families separated, and whole cities rewired overnight by borders slicing through soil and memory both. Amidst this vast disruption, another lesser-known story was unfolding. It was the tale of books—libraries torn out of context, manuscripts destroyed, and whole sets of knowledge smuggled across borders as individuals took small pieces of their world of ideas with them.

To talk of Partition is commonly to talk of bodies and trains, of camps and columns of refugees. But there is another dimension of loss that touches the heart as much as the intellect. Libraries, in their vulnerable silence, contain a civilisation’s memory. When they are breached, it is as if a community’s voice is muffled. Partition in 1947 was not just a matter of geography and politics but also of dispersal of tales, dispersal of knowledge, and silencing books.

The World of Libraries Before Partition

Prior to 1947, northern India was filled with scholarly collections. Lahore, for example, was regularly termed the intellectual capital of Punjab and was graced with libraries that contained Persian manuscripts, Urdu poetry, Sanskrit works, colonial archives, and journals of contemporary thought. The Punjab University Library in Lahore and the treasure trove of materials at Aligarh, Delhi, and Calcutta were treasure houses of centuries-long dialogue between tradition and modernity.

Private libraries also thrived, usually lovingly gathered by families that treated books as a family heirloom. Rich families, along with poor scholars, guarded their manuscripts in wooden trunks, reading rooms, or little shrines at home. These collections stored not only religious works but also romances, histories, and treatises on astronomy and medicine. They comprised a world of ideas that was porous, cosmopolitan, and pulsating.

This was the intellectual environment that Partition would destroy.

The Rupture of 1947

While violence broke out in Punjab and Bengal, the security of books became a minor issue in the face of saving human lives. But when the people were escaping, many would automatically grab manuscripts, letters, and books that symbolized their heritage and scholarship. Examples are numerous of scholars who took loads of books on their backs, children holding storybooks as they evacuated from their homes, and families who stashed manuscripts along with clothes and kitchenware in chests.

Public and private libraries lost tremendous amounts of material. The Lahore Museum and its collections were contentious. Punjab University Library manuscripts were split between India and Pakistan, a process marred by confusion, suspicion, and heartache. In Delhi, Aligarh, and Lucknow, the same scenario of abandoned, plundered, or dispersed collections was repeated.

Mob violence did not spare books. Houses that were set alight with fires also saw their libraries go up in flames. In others, manuscripts centuries old were reduced to ashes as refugees fled with only the clothes on their backs. Generations of accumulated knowledge were lost in a matter of days.

The Smuggling of Knowledge

Partition also produced bizarre and frequently tragic stories of smuggling. Families wrapped scrolls in cloth and snuck them hidden in the midst of cooking implements. Others ripped pages out of their favorite works, unable to transport a whole library but not willing to forego every hint. Books were contraband of the heart, things for which one would risk death.

At station yards, where luggage was rifled and crowds roamed, citizens inserted small volumes into clothing. Some experts even traded food or treasures for the safe conveyance of their libraries. Libraries that could not be transported were sometimes entombed in courtyards or placed in wells in the belief that some day the family would return.

Not all of these hidden collections survived. Some rotted, were looted, or were never seen again. But a few did, resurfacing decades later as forgotten trunks full of brittle pages, reminders of a lost world that still had something to say.

The Partition of Institutions

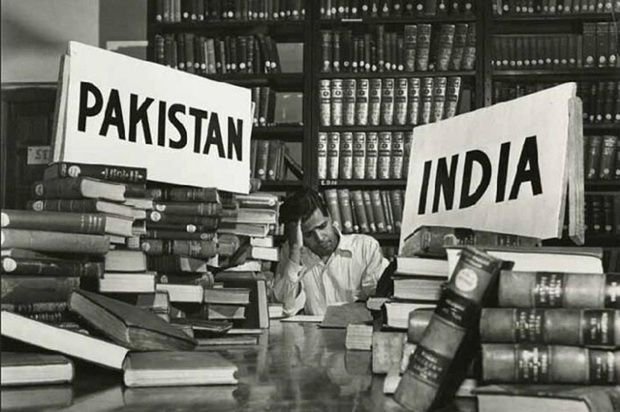

The separation of libraries was not merely personal but also institutional. The partition of Punjab University, for instance, involved dividing books between the new India and Pakistan. Panels of experts were established to determine which texts would go where, an administrative attempt to divide knowledge itself. It was a task impossible to please everybody. Will a manuscript of Persian poetry be sent to Lahore due to geography, or sent to Delhi due to linguistic continuity? Did a scientific treatise belong to “modern” India or “new” Pakistan?

These questions testified to the folly of creating boundaries through culture. Knowledge is not blind to boundaries on a map. To separate books was to try the impossible: to divide memory.

Human Voices Among the Books

What brings this story to life are the little things that linger in oral accounts. A refugee remembering how his father cried not for lost homeland but for a torched library. A woman who kept her grandmother’s Quran as the sole memento from a home abandoned. A professor who reconstructed his life of teaching in Delhi with little but some salvaged manuscripts from Lahore.

These are tales in which books transcend objecthood. They are friends, identity anchors, shreds of continuity when all else was broken. To see refugees lugging books along with pots and blankets is to realize that knowledge itself is nourishment.

The Long Aftermath

Partition scars libraries continue to bear even today. Indian and Pakistani collections still retain the mark of rushed partitions. Manuscripts go missing, catalogues are incomplete, and provenances unsure. Scholars frequently find that the books they are looking for disappeared in 1947, swept up in the wave of violence and displacement.

Meanwhile, Partition also established new libraries. Refugee intellectuals reconstructed collections in Delhi, Lucknow, Karachi, and Lahore. Memories of books lost sometimes became the seed for new attempts at preservation. In this respect, Partition did not merely destroy but compelled renewal, albeit at a cost too burdensome to be legitimized.

Conclusion: Remembering Through Books

Partition libraries’ tale is not as apparent as refugee trains or camps of survivors, but it is one with deep resonance. Losing a book is losing a voice, and 1947 muffled hundreds of such voices. But the pieces that remained, the manuscripts sneaked in, the texts torn, remind us of the determination of human beings who, even amid impossible violence, wanted to carry knowledge with them.

It is easy to quantify Partition exclusively in terms of geography and numbers. But the book-smuggling informs us about something more profound: human beings do not survive on bread alone. They have the stories, the songs, the wisdom with which to endow survival.

To recall Partition, therefore, is not merely to lament the millions who were killed but also to respect the books that disappeared and the bravery of the people who salvaged what they could. In the quiet of those missing libraries, there remains a call to cherish information, to hold memory, and to keep alive in the midst of chaos the voices of the past.