Tea and Empire: How a Drink Built the British Raj

-Vani Mishra

There are times in history when the plainest objects bear within them the burden of empires. Tea, that unassuming brew of leaves and water, was one such force. For Britain, it was not just a drink; it was a cultural fixation, a source of vast wealth, and a rationalization for empire itself. For India, it became an industry imposed on it and soon a national one. The narrative of how tea became wedded to the British Raj is not one of mere trade but one of power, labor, land, and the remaking of daily life.

The Arrival of Tea into the British Imagination

When tea came to England in the seventeenth century, it was a Chinese import, an exotic luxury. The East India Company transported it across seas, and by the eighteenth century, tea had become a common fixture in British homes. Drinking tea meant enjoying a ritual that spanned classes: it was chic for the upper classes and soothing for labourers who found in it a daily pick-me-up.

But reliance on Chinese tea was a problem of a serious nature. The British did not have much that China needed in return. This trade imbalance resulted in the export of silver and ultimately to the opium trade, which ended in the Opium Wars. The desire for tea, therefore, was more than a matter of cultural choice; it was an economic driver that required new solutions.

India Becomes a Tea Colony

The answer the East India Company discovered was India. In the early nineteenth century, there was a revolutionary discovery of wild tea plants in Assam. There was the chance now to plant tea within imperial borders and liberate Britain from dependence on Chinese imports.

Plantations were set up, initially in Assam and subsequently in Darjeeling and elsewhere. These were not natural developments of indigenous farming but precisely constructed ventures intended to benefit the empire. Forests were felled, land was taken, and whole landscapes were transformed into tea estates.

The cost to humans was enormous. Workers, usually recruited from tribal and poor communities, were taken to labor under harsh conditions. Under oppressive contracts, they endured excessive hours of work, illness, and minimal possibility of escape. The steamy plantations of Assam became the pride and secret shame of the empire.

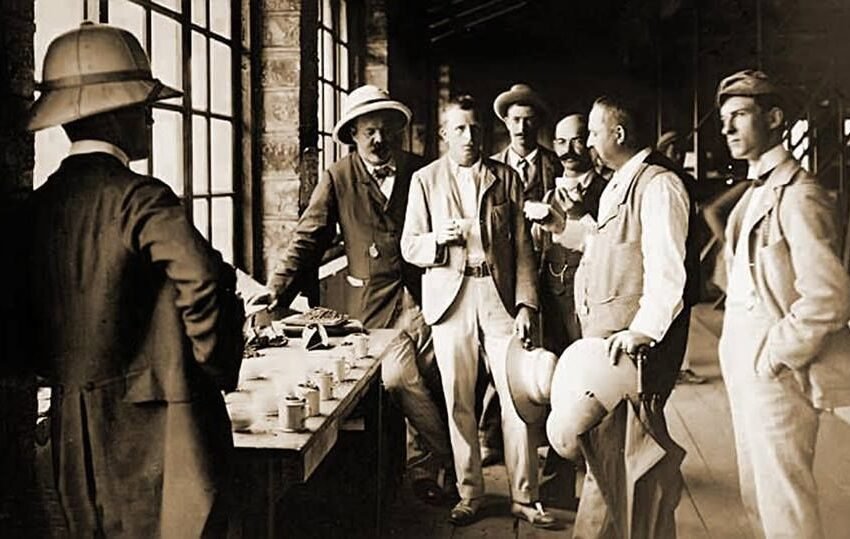

Tea as a Symbol of Empire

Tea was not merely made in India; it was sold as India’s contribution to the world. The empire left an impressive legacy: Indian tea was clean, stimulating, and better. London exhibitions revealed the voluptuous look of tea plantations. Advertisements presented tidily dressed pickers in idyllic settings, suppressing the bleaker facts of work. This imagery validated imperial ideology. To consume Indian tea was not just to rehydrate but to engage in the civilising mission of empire. The cup of tea became a quiet ritual in which British subjects, both at home and overseas, asserted their position within an immense imperial structure.

The Indian Response: From Resistance to Adoption

Originally, tea was not a part of everyday life in India. Coffee, milk, lassi, and herbal teas were all popular, but tea drinking was unknown to a large extent. The British tried to change this. Tea was promoted as clean and modern through campaigns. Spiced tea was encouraged to be sold on railway platforms by vendors. Tea gradually entered village kitchens and city stalls.

But Indian adoption of tea was not simply imitation of the British. It was altered. Indians added milk, sugar, and spices to make chai—a beverage with a distinct identity all its own. What was once an imperial imposition became one of the most popular and unifying drinks of contemporary India.

The Economics of Empire

By the late nineteenth century, tea was becoming one of the pillars of India’s colonial economy. Revenues on a massive scale flowed to Britain in the form of export profits, and Indian workers were caught in cycles of poverty. Plantations were controlled by and belonged to largely European communities, and profits seldom remained within India.

The logic of economics was straightforward: India made things, Britain used them, and the empire prospered. That teacup on a table in London was directly connected to the toil of an Assamese labourer or the felling of Himalayan woodlands. Each sip was a testament to the imbalance of empire, even if the consumer did not know it.

Tea and the Politics of Identity

Tea became political over time as well. Nationalists referred to the exploitative nature inherent in plantations. Authors wrote of the hard conditions of workers and condemned the export-oriented economy. Tea, meanwhile, became a site of modern Indian identity. To enjoy chai was to embrace communalism, to share in a ritual that bridged class, caste, and region. Gandhi himself, while denouncing plantation exploitation, admitted the space tea had now found in Indian life. It was, paradoxically, both a reminder of imperialism and a common solace that ordinary Indians took for their own.

The Legacy of Empire in a Cup

Now, India is a leading tea-producing nation, and chai is an integral part of daily existence. In railway stations, in offices crowded with people, in tea stalls on the roadside, tea is that one beverage that brings people together during pauses and conversation. The colonial origins of the industry are easily forgotten amidst the conviviality of the shared cup.

But history remains. The Assam and Darjeeling tea estates are still there, with their histories of inequality and memories of forced labour. The very landscapes carry the marks of colonial ambition. To research tea is thus to learn about how empire remade economies, environments, and cultures.

The Empire in the Everyday

The tea and empire story teaches us that history is buried in the most mundane of things. A cup of tea is a humble thing, but in its scent is the story of conquest, toil, and adjustment. It bears with it the memory of forests felled, of labourers stooping under monsoon rains, of boats traversing oceans, of Parlors in London where empire was drunk from porcelain cups.

And it bears resilience. For from this past, India created chai something born of itself, a beverage which made empire’s heritage local, cherished, and communal. With each cup of chai, there is an echo of empire, but also the flavour of survival and transmutation.