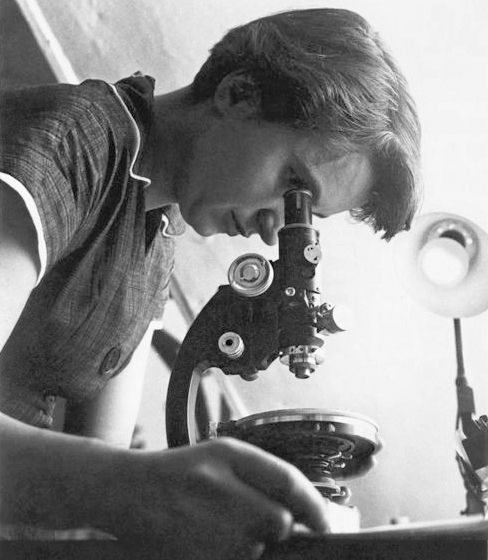

The Unsung Hero: Rosalind Franklin

-Bhoomee Vats

Born in London on July 25, 1920, Rosalind Elsie Franklin was part of a well-known family of Anglo-Jewish scholars, leaders, and humanitarians for whom education held high value and importance. Just like her family, Rosalind was a very intellectually smart child, and according to her mother, “all her life she knew exactly where she was going and took science for her subject” at 16. She was a dedicated, devoted, and gifted student with a keen sense of justice and logic and an intrigue for languages. She thrived on intellectual debate and thrived on challenging others to justify their opinions and positions, a method she used throughout her life to learn more, to teach more, and to clarify her understanding.

Rosalind was not only a bright student but also a devoted daughter and sister, and loyal and gracious to her many friends and fellow workers. Her family members remember her as a woman with a lively sense of humour, who was straightforward and loved cooking. She was also an experienced mountaineer who loved travelling and exploring nature and many other places. Franklin family vacations were often walking and hiking tours, and hence hiking became one of Rosalind’s lifelong passions, so did foreign travel. Not just limited to these talents, but she also had little ear for music; Gustav Holst, a then music director at St. Paul’s, once noted that Rosalind had improved to the point of singing “almost in tune.” Franklin family vacations were often walking and hiking tours, and hiking became one of Rosalind’s lifelong passions, as did foreign travel.

Education

Rosalind’s early education was in private preparatory and boarding schools, which prepared her for enrolment in Newnham College, one of two schools for women at Cambridge University. She majored in and studied physical chemistry and made herself more than eligible for the scholarship. Though she faced many challenges in her lifetime, she refused to let them defeat or define her. She gradually, with a lot of devotion, pursued her education during World War II, despite the bombs that rained down on London during the Blitz, despite shortages and rationing, and despite family pressure to leave Cambridge for safer ground and, perhaps, for work aiding the war effort. While the Nazis marched across Europe, she continued to pursue her studies while closely following every headline of the war and debating British foreign policy in letters to her family, and also volunteering as an air raid warden.

Her excellence in studies and her exam scores earned her a graduate research scholarship, a grant from the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, providing her with an excellent reason to stay at Cambridge despite the war and chaos. Rosalind earned a bachelor’s degree in 1941, and the next year, as more women moved into academia and industry, she accepted a position with the British Coal Utilisation Research Association, where she carried out and conducted experiments to understand the microstructures of carbons and coals, a work that ultimately benefited the Allied (Great Britain, France, and Russia) cause. In 1950, she was awarded a three-year Turner and Newall Fellowship to work in John T. Randall’s Biophysics Unit at King’s College London, where she started investigating DNA samples.

Rosalind and DNA

Franklin worked with a student named Raymond Gosling and was able to get two sets of high-resolution photos of crystallised DNA fibres. She used two different fibres of DNA, out of which one was more highly hydrated than the other. From this, she figured out the basic dimensions of DNA strands and also that the phosphates were on the outside of what was probably a helical structure. She then went on to present her data at a lecture in King’s College at which James Watson was in attendance. In his book The Double Helix, Watson admitted to not paying attention to Franklin’s talk and not being able to fully describe the lecture and the results to Francis Crick. Watson and Crick were at the Cavendish Laboratory and had been working on solving the DNA structure. It was Maurice Wilkins who showed Watson and Crick the X-ray data Franklin obtained.

The data confirmed the 3-D structure that Watson and Crick had theorised for DNA. In 1953, both Wilkins and Franklin published papers on their X-ray data in the same Nature issue with Watson and Crick’s paper on the structure of DNA. Franklin then left Cambridge in 1953 and went to the Birkbeck lab to work on the structure of tobacco mosaic virus. She published several papers on the subject, and she did a lot of the work while suffering from cancer. Four years after Franklin’s death, Dr. Watson and Dr. Crick, along with Dr. Wilkins, accepted the 1962 Nobel Prize for the discovery and description of the structure of DNA, while Rosalind’s brilliant illumination and critical data analysis went largely uncredited and unnoticed

Conclusion

Rosalind Franklin’s legacy lives on through her science and work, which continues to bring great value to humankind, in the form of her love for the natural world. She set high standards for herself and others and pursued answers to her questions despite the many obstacles she faced with devotion. She believed that “Science and everyday life cannot and should not be separated.” She published consistently throughout her career, including 19 papers on coals and carbons, five on DNA and 21 on viruses. Shortly before her death, she and her team, including Dr. Klug, who won the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1982, embarked upon research into the deadly polio virus.

The discovery of the structure of DNA sparked a revolution in the biological sciences and technology and expanded knowledge in many other fields. Based on the structure of DNA, the new science of molecular biology was born, leading to prevention, diagnosis and treatment in ways that were unimaginable in 1952. The advances in identification and analysis of the genetic code based on Dr. Franklin’s work have produced breakthroughs that changed the trajectory of science and will continue to improve the human condition. On Jan. 27, 2004, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science became the first medical institution in the United States to recognise a female scientist through an honorary namesake.